Highlights from TCEQ’s Advanced Air Permitting Seminar 2022

In the fall of most years, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) hosts an Advanced Air Permitting Seminar to provide air permitting and regulatory updates to its attendees. There were a few hot topics discussed this year, which included:

- The official ozone redesignations date (and impacts),

- The new public involvement plan requirements,

- Title V Actions and the New Source Review (NSR) Implications, and

- Other Updates.

The updates from the seminar are summarized in this article, and the slideshow presentations from the seminar can be found on the TCEQ’s website.

Ozone Nonattainment Bump-up Status

The ozone redesignation standards will come into effect on November 7, 2022. The following table summarizes the new thresholds post-bump up for the affected regions (Houston-Galveston-Brazoria (HGB)/Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW) and Bexar counties). Please note, there are 2008 and 2015 ozone standards for the areas, but it is required that the major source evaluation occur against the most stringent threshold that is in effect, which is what is provided below.

| Texas Area | Ozone Standard (Year) | New Classification | Major Source Threshold (tpy) | Major Modification (tpy) | Netting Threshold (tpy) |

| HGB/DFW | 2008 | Severe | 25 | 25 | 5 |

| Bexar | 2015 | Moderate | 100 | 40 | 40 |

The bump up has air permitting implications for both the Title V Operating as well as New Source Review permit programs. Any air permit applications that have not been approved (i.e., final signature and issuance from TCEQ) before the ozone redesignation comes into effect will be subject to the new standards and must be re-assessed as applicable. Existing sites that were previously minor sources and now fall under the major source category have 12 months to apply for a Title V Operating permit.

As part of the webinar series that ALL4 is currently offering on updates to the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), our team recently presented “New Zones for Ozone NAAQS” and covered the ozone updates. The recording is available on the ALL4 website and can help you understand the implications of these designations. Part 1 of the webinar series was called “NAAQS to Basics,” and can provided information on NAAQS setting, and Part 3 of the series will be provided in December for updates to the Fine Particulate and Lead NAAQS. You can sign up for our webinars via the ALL4 website.

Public Participation and the new TCEQ Public Involvement Plan (PIP)

In response to the Title VI complaint filed against the agency in 2019, TCEQ has been making updates to their public notice requirements, including updates to the public participation plan and language access plan. Earlier this year, we saw an update requiring alternative language notice requirements and alternative language public participation in the public notice process from postings to public forms, and the new requirement of a Plan Language Summary form for all applications subject to Chapter 39.

As of November 1, 2022, the TCEQ will require the new Public Involvement Plan (PIP) (TCEQ Form 20960) for all multimedia applications (not just air) and applicable standard permit registrations (that require public notice) that meet all 3 of the following criteria: 1) new applications and/or activities requiring notice 2) have significant public interest, and 3) are within the following geographical regions: Urban metroplexes, West Texas, Panhandle, and the Texas/Mexico border. The form must be part of the initial submission, and the purpose of this plan is to allow facilities the opportunity to discuss their public outreach and involvement plans for projects being submitted. The first section of the form is the preliminary screening, and if you screen out, then you do not need to submit the form. All three of the criteria must be selected in Section 2 to proceed to Section 3.

Title V Actions and the NSR Implications

In June 2021, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) issued 12 new orders for Title V Operating permits and has objected to several Title V Operating permitting actions during the 45-day review period in Texas. There have been ongoing discussions between the U.S. EPA, TCEQ and the applicants on the resolution. Due to these actions, TCEQ will be focused on the following items as they continue to permit projects, with a heavy focus on better defined monitoring, recordkeeping, reporting and testing requirements for both NSR and Title V:

- Permits By Rule (PBRs) in Title V Operating Permit Applications: All Federal Operating Permits (FOPs) will require the OP-PBRSUP table be submitted with all PBRs in the application area listed. The form must contain monitoring requirements for registered and claimed PBRs.

- Monitoring and Demonstration of Compliance for both NSR and Title V: Conditions will likely be updated to reference less ambiguous monitoring and testing methods, and historical data (such as stack tests) or short-term averaging periods (i.e., 3 hours) may be revisited and updates may be required, including a new stack test to demonstrate compliance.

- If an applicable requirement or permit term references an item in a NSR application or PBR registration, it must not be confidential.

- A closer look will be taken at NSR conditions that are referenced within Title V Operating permits to ensure that the NSR condition has the specific information outlined that ensures monitoring requirements can be met.

As part of these actions, NSR special conditions will also be reviewed and revisited to ensure there is no ambiguity in the language and TCEQ may start requesting actual procedures used to meet a condition. If a plan or calculation methodology is referenced in the condition, it is likely that the specific calculation page or plan will be added to the reference (e.g., a page number associated with an application submitted on October 21, 2022). Historical stack test references will be revisited and may require re-testing (if the stack test was done over 10 years ago), and maintenance, start-up, and shutdown (MSS) monitoring conditions will be updated to add more specificity to the methodologies used.

Other updates

- PBR 106.261/262 updates: The TCEQ is working on making updates to the 261/262 workbooks which will be rolled out in the near future. There was discussion on the New Hour Footnote for PBRs 106.261/262 for projects where there is an increase in annual emissions but no increase in hourly emissions. These emissions can be authorized via PBR if hourly emissions stay below current authorized emissions limits, there is no change to any underlying air authorizations for the applicable units associated with BACT or health and environmental impacts, and the claim is certified via PI-7 CERT with no circumventing of major new source review requirements under 30 TAC Chapter 116. In addition, PBRs must be evaluated based on an old actual to new potential emissions increase, and for a site that is authorized via PBR only, the emissions must be evaluated on a sitewide basis for PBR applicability.

- As of October 27, 2022, applicants can submit their Title V Operating permit applications via STEERS.

- The U.S. EPA has proposed a reconsideration of the fugitive emissions rule, and TCEQ will be making appropriate updates once that goes into effect.

- There is a new ERC Generation General Workbook that was required to be used on October 1, 2022 as part of the Emissions Banking and Trading program. The workbook can be submitted via STEERS.

- An update to the fugitive workbook was rolled out earlier this month, and included the ability to identify unique components and calculate emissions for those components not defined in the fugitive guidance, as well as a summary tab summarizing total emissions quantified in the workbook.

Contact Information

With the new ozone bump-up standards, the new focus on public outreach and participation, as well as the focus on Title V Operating and NSR permit condition specificity, there will likely be more updates and requirements in the future from the TCEQ. ALL4 will be publishing any updates and requirements as they arise. For any questions or assistance with any of the items discussed in this article or for any Texas-related permitting questions, please contact me at 281.201.1251 or at relafifi@all4inc.com.

Decarbonization in the Cement Industry and the Role of the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi)

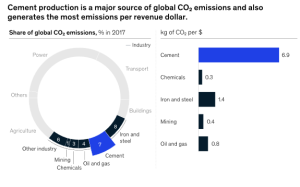

Like the power and transportation industries, decarbonization of the cement industry is crucial for meeting the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) Paris Climate Agreement to limit global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. The Paris Agreement roadmap includes a goal to reduce global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 45% by 2030 and to reach net zero by 2050 to combat climate change. Currently, the cement industry is the third-largest industrial energy consumer and the second-largest industrial carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter in the world, representing about 7% of global CO2 emissions. “The cement industry alone is responsible for about a quarter of all industry CO2 emissions, and it also generates the most CO2 emissions per dollar of revenue.” In addition, “around two-thirds of the cement CO2 emissions come from the calcination of limestone.” As a main ingredient to concrete, and with the demand for cement projected to climb steadily for years to come, action must be taken to optimize and decarbonize cement consumption in buildings and construction including finding methods that are less carbon intensive and more sustainable. This is key to help society meet the GHG emission reduction goals and help slow the effects of global climate change.

Source: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/chemicals/our-insights/laying-the-foundation-for-zero-carbon-cement

The cement industry faces many challenges in today’s marketplace, including supply chain disruptions from events such as geopolitical disagreements and global pandemics, and more prominently from pressure from investors and stakeholders to incorporate environmental, social, governance (ESG) practices into management and operations. These pressures loom large on the cement industry and make it difficult for companies to come up with effective management strategies to start their sustainability journeys effectively and with transparency.

One organization that is leading the way to assist companies with setting targets and strategies to meet the Paris Agreement’s net zero goal is the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi). The SBTi was launched in 2015 to help companies align GHG reduction with climate science to avert the impacts of climate change and provide a resource for peer benchmarking. The SBTi is a collaboration between the CDP, the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), the World Resources Institute (WRI), and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) with a goal to assist companies with setting science-based climate targets to decarbonize the planet. The guidance the SBTi provides publicly assists companies with figuring out how much and how quickly they need to reduce their GHG emissions to align with the Paris Agreement. The SBTi drives ambitious climate action in the private sector by enabling companies to set targets that are in line with sector standards and benchmarking. The SBTi’s success is demonstrated by the number of companies utilizing the standard today, with over 3,865 companies, that collectively hold a third of the global economy, involved.

The SBTi has developed science-based target setting methodologies, tools, and guidance specifically for the cement industry and other cement-related stakeholders. The recently launched Cement Science Based Target Setting Guidance is the world’s first known framework for companies in the cement industry and aims to assist companies with setting their near- and long-term science-based targets in line with the Paris Agreement. The guidance provides details on how to set targets and deal with processes that are specific to the cement and concrete sector, GHG accounting criteria and recommendations, as well as examples on how different types of companies can use the tools and guidance to submit a target for validation. Ultimately, the SBTi’s cement guide aims to specify how much and how quickly a company would need to reduce its GHG emissions in order to align with the 2050 net zero goals.

At the current moment, carbon reduction strategies in the cement industry have relied heavily on improving equipment and energy efficiency measures. “Today, the most efficient cement plants can squeeze only 0.04% of energy savings per year by upgrading technologies. More needs to be done.” With many of those initiatives already implemented, it’s clear that a much more multifaceted and collaborative cement ecosystem approach will be needed to offset total emissions from global cement production. As the SBTi presents in their cement guidance, the decarbonization of the cement industry will need to include a variety of techniques and strategies to meet the Paris Agreements net zero goal. The following priorities are a few areas of action and research that the SBTi lays out in their guidance to assist cement companies decarbonize their processes:

- The reduction of cement consumption: Using less concrete has the potential to reduce the demand for cement significantly. This can be done through building codes changes, better education for architects and construction workers, and more recycling and reuse of concrete.

- The use of the latest building and manufacturing technologies: Ensuring that production plants are fitted with the best available technology offers immediate gains. Improving insulation of industrial plants can save 26% of the energy used; better boilers cut energy needs by up to 10%; and use of heat exchangers can decrease the power demands of the refining process by 25%.” There is also a lot of opportunity for growth in how technology can assist emission heavy industrial sectors, as stated by Brian Deese, the Biden administration’s Director of the National Economic Council; “On the industry side, both investing in R&D and in the deployment of new technologies that will help US industry lead in creating low-carbon or zero-carbon industrial applications to the future, whether that’s low carbon materials, steel, cement, or in zero-carbon areas like CCS and hydrogen. Those are places where you need public investment to help unlock new breakthroughs. And we have a big stake in having that innovation happen in the United States and then having the manufacturing happen co-located with the innovation.”

- Developing new low-carbon cement varieties and reinventing the steel product: This includes making cement with limestone alternatives, using other cement variants that are low carbon, replacing some of the clinker with more sustainable materials including blast-furnace slag and ash from coal-fired power stations. An example of a new low carbon cement is known as carbon-free activated clay-based cement.

- The substitution of low-carbon energy sources for fuel and electricity: This includes the use of hydrogen, solar, wind and other renewable energy sources.

- The promotion of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology: This includes capturing carbon dioxide released from combustion and process sources and storing it underground or otherwise using it. Although the potential for carbon capture is quite high, the technology is not yet to scale. CarbonCure, a company that specializes in injecting CO2 into a concrete mix, and a leader in the space, states that most producers of cement using its technology only achieve CO2 emissions reductions of 4% to 6%. There is still a lot of growth and innovation needed in the CCUS arena to assist with the net zero goal and, as stated by the American Chemical Society, “most CO2 recycling technologies are still emerging, and their development has to be boosted in the next decades”.

- Proper governance: This includes effective policies and stakeholder engagement throughout the cement industry’s value chain that encourage sustainable development.

As pressure from stakeholders increases and the sales of traditional cement faces threats of non-viability, the combination of new technology, innovation, new ways of thinking, and new business models will be essential to ensuring a low carbon future that is sustainable for the cement industry. Working with the SBTi and using its Cement Science Based Target Setting Guidance will provide the support cement companies require to start their decarbonization journeys making sure they are robust, clear, and practical. It is vital that industries such as the cement industry collaborate and push each other to find innovative ways to decarbonize their industry.

If you would like to learn more about how ALL4 can assist your company with its environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals, including setting a scienced-based target with the SBTi, please reach out to James Giannantonio at jgiannantonio@all4inc.com.

Sources:

https://sciencebasedtargets.org/sectors/cement

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c06118

https://sciencebasedtargets.org/sectors/cement

https://www.nrdc.org/experts/sasha-stashwick/carbon-capture-concrete-could-one-day-be-carbon-sink

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00758-4

https://www.enr.com/articles/54809-new-technologies-for-reduced-carbon-concrete-are-on-the-horizon

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352728516300240

Reconsideration of the 2008 Fugitive Emissions Rule – What Does it Mean for Your Next Project?

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) is proposing to fully repeal the 2008 Fugitive Emissions Rule that has been stayed, in some form, since September 2009. The U.S. EPA is also proposing to remove an exemption for modifications that would be considered major solely due to the inclusion of fugitive emissions. As a result of the proposed changes, all existing major stationary sources would be required to include fugitive emissions in determining whether a physical or operational change constitutes a ‘‘major modification,’’ requiring a permit under the Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) or Nonattainment New Source Review (NNSR) programs. Importantly, fugitive emissions may continue to be excluded when determining whether a facility is a new major stationary source if the facility is not one of the 28 listed categories required to include fugitive emissions in 40 CFR 52.21(b)(1)(iii). As such, this reconsideration affects only non-listed, existing major stationary sources. U.S. EPA believes a limited number of sources have invoked the fugitive exemption but does not address whether sources that did invoke the exemption would be required to retroactively review major modification determinations.

Fugitive emissions are defined in 40 CFR 52.21(b)(20) as “those emissions which could not reasonably pass through a stack, chimney, vent, or other functionally equivalent opening.” Common examples of fugitive emissions include particulate matter (PM) emissions from material handling, wind erosion of storage piles or surface mines, and roadways, and volatile organic compounds (VOC) from leaking equipment. In 2008, EPA said that the cost of controlling emissions could be considered when determining whether emissions “could not reasonably pass” and be considered fugitive. With this proposal, EPA says cost of control should not be relied upon in making fugitive vs. non-fugitive permitting decisions. EPA suggests relevant considerations may be the extent to which similar facilities collect or capture similar emissions, how common the practice is, whether a federal standard has been established requiring some facilities to capture the emissions, and technical and economic cost of collecting or capturing (versus controlling) emissions. Specifically, for purposes of major NSR, once a project is considered a major modification for a particular pollutant, all emissions including fugitive emissions must be included in subsequent analyses including Best Available Control Technology (BACT) and ambient air quality impact analyses.

Fugitive emissions are challenging to characterize and quantify. Emissions are often based on engineering judgement and err on the side of conservatism. Source test data is limited due to the very nature of fugitive emissions and the challenge of capturing these emissions to accurately measure them. Add-on control technology is often infeasible due to these same challenges, forcing industry to rely on work practices like minimizing drop heights and watering of roadways at best to minimize emissions. Some facilities may have opportunities to work with industry work groups to better understand and characterize fugitive emissions. If you haven’t previously included fugitive emissions in your project increases, ALL4 recommends utilizing available means to refine fugitive emissions calculations.

Modeling of fugitive particulate matter emissions is equally challenging with the highest impacts typically occurring on and near facility fence lines. U.S. EPA’s particulate matter less than 2.5 microns in aerodynamic diameter (PM2.5) modeling guidelines now require a source to model primary PM2.5 if the project is a major modification for sulfur dioxide (SO2) or nitrogen oxides (NOX), even if PM2.5 emissions increases are less than the major modification significant emissions rate. If modeling results in impacts at or beyond the fence line that are greater than the PM2.5 modeling significant impact level, a cumulative modeling demonstration is required. The cumulative modeling demonstration includes site-wide PM2.5 emissions, off-property PM2.5 emissions, and background concentrations. States will often provide off-property emissions inventories for these analyses, but many times these inventories lack PM2.5 data and fugitives data (e.g., roadways), requiring research and even contacting of surrounding facilities to obtain data.

While most of these challenges are not new and facilities in the 28 listed source categories have been navigating these issues for many years, this rule would cement U.S. EPA’s position with respect to fugitive emissions and PSD/NNSR. Lack of data, conservative assumptions, and limited air pollution control options for fugitive emissions could be the tipping point for a proposed project resulting in a major modification, which will lead to a challenging and lengthy permitting process.

Comments on the proposal must be received by December 13, 2022. If you have any questions regarding the reconsideration of the fugitive emissions rule or would like assistance with commenting on the rule, please contact Jenny Brown at jbrown@all4inc.com or Amy Marshall at amarshall@all4inc.com.

Georgia to Require Electronic Discharge Monitoring Report (eDMR) Submittals

Background

The Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GAEPD) will require the electronic submittal of Discharge Monitoring Reports (DMRs) starting in 2023 using Network DMR (NetDMR), which is a web-based application created by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. NetDMR allows permittees to report through a Central Data Exchange to an Integrated Compliance Information System. The process is intended to reduce paperwork, improve DMR quality, timeliness, and accessibility, and provide instant confirmation of submission. DMRs may currently be submitted electronically using the GAEPD Online System (GEOS) or by sending hard copies to GAEPD via return receipt certified mail (or a similar service).

New Requirements

Beginning January 1, 2023, all stormwater discharge monitoring data collected per the GAEPD National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) General Permit for Stormwater Discharges Associated with Industrial Activity (GAR050000) must be reported on a quarterly basis using NetDMR. This permit was re-issued on June 1, 2022, and the NetDMR reporting requirement applies to all permit holders. The monitoring data includes indicator, benchmark, and impaired waters sampling results. The required monitoring parameters and frequencies will be pre-populated on the DMR based on the information provided on the Notice of Intent (NOI) that was filed to obtain coverage under GAR050000. If pre-populated information on the DMR needs to be changed due to a condition-specific nuance, the permittee is required to contact GAEPD. DMRs are required to be submitted within 45 days of the end of each calendar quarter. A DMR must be submitted for every monitoring period even if no monitoring was completed.

Failure to submit a DMR on time is a violation of the permit. Permit non-compliance could lead to enforcement actions, including permit termination, fines of up to $25,000 per day for each violation, and imprisonment for up to one year. Penalties increase for willful and repeat violations.

What Do Permittees Need to Do?

To get started with NetDMR, the permittee will need to create an account on the NetDMR website and then follow the prompts. Annual Reports required by GAR050000 must still be submitted to GAEPD on an annual basis via the GAEPD Online System (GEOS). Monitoring and sampling data for the period from the effective date of GAR050000 until December 31, 2022 must be reported with the 2022 Annual Report, which is due January 31, 2023.

ALL4 is available to assist with NetDMR set-up and/or data entry once the requirement goes into effect or any of your other permitting and compliance needs. If you have questions about using NetDMR, please contact Anna Richardson at arichardson@all4inc.com or Adam Czaplinski at aczaplinski@all4inc.com.

How Do I Know if My Project Needs an Air Permit?

There is not a whole lot that is black and white about air quality permitting. It can sometimes be hard to determine whether you need to submit an air permit application for a project and if so, what kind. The goal of this article is to provide some concepts and questions to consider when you are developing projects so that you can reach out to your favorite air quality expert to help you determine if your project needs an air permit.

What is a Project?

You might not think what you are planning to do at your facility rises to the level of being an air permitting project, but you should consider the following questions to help you determine whether your project meets the criteria of an air permitting project:

- Are there capital costs associated with the project being considered?

- Does someone have to pick up a wrench, saw, screwdriver, or other tool that will come into contact with something that is on my air permit or serves something that is on my air permit?

- Are you going to install new equipment that has associated air emissions?

- Are you going to install equipment or make a change that will make existing equipment have more associated air emissions?

- Are you changing a process control system so that you will be able to make products more efficiently and increase throughput?

- Are you relieving a “bottleneck” in your process?

- Will your project result in reduced process down time?

- Are you proposing to do something that your air permit does not allow you to do now?

If the answer is yes to any of these, we need to dig a little deeper.

What if my Project Does not Require any Changes to my Permit?

Sometimes staff charged with evaluating projects think that an air permit application is not required because they do not want to make any changes to the air permit. Even if your project does not contravene or conflict with any conditions in your air permit, you may still need to submit an air permit application. If you are making a “physical change” or a change in the way you are operating that will increase the air emissions the environment actually sees, you need to evaluate the possible need for air permitting. Simple example: Say you permitted your facility to emit 100 units of emissions, but the environment has only ever seen 50 units of emissions in the ten years that you have operated. If you are making a change that now allows you to achieve 100 units of emissions, you will increase actual emissions as a result of your project and will need to evaluate the appropriate air permitting mechanisms. The right question to ask is whether the project increases the emissions that the environment actually sees, not whether the project increases emissions or throughput above my currently permitted levels.

What Questions Should I Consider when Evaluating my Project?

You should consider the following when evaluating project impacts. Will this project/action:

- Result in an actual production/throughput increase?

- Remove any existing production constraints or capacity restrictions?

- Result in greater available hours of operation/less downtime?

- Require a physical change to the process or process control system?

- Result in the use of new and/or greater quantities of fuel or raw materials?

- Result in process chemistry changes at the facility that impact emissions?

The question is whether your project will result in an actual increase in emissions of any regulated pollutant, not just whether it will increase potential emissions or capacity.

Are there Changes that are Exempt from Permitting?

The short answer is yes. If you can increase hours of operation at your facility without making any changes and your permit does not restrict you from doing so, that action is not likely to need air permitting. Your permitting agency may have a list or description of types of activities that do not need to be permitted (and permitting requirements differ by location). Projects that are considered routine maintenance, repair, or replacement (RMRR) are not modifications. However, figuring out whether something qualifies as RMRR requires an evaluation of the nature and extent of the work; the purpose of the work; the typical frequency of the work; and the cost of the work. For example: changing the oil and replacing filters in your car is RMRR but replacing the engine is not. If you are replacing a unit with a bigger unit that will get you more throughput – that’s not RMRR. If you are replacing your old dingy thing with a new shiny thing because the old dingy thing is at the end of its useful life and you need to replace it to keep your plant running, that is not RMRR, it is a modification that likely needs to be permitted.

What does my Favorite Air Quality Expert need to Know to Tell me if my Project Needs an Air Permit?

If you think your project might need an air permit based on your consideration of the items above, it probably does. Here is what your favorite air quality expert needs to know to determine whether an air permit application is needed for sure, and what type:

- Are you installing new equipment?

- How big is it?

- What fuel does it burn to operate?

- Will it need steam and if so, how much steam will it need?

- Any emissions control equipment?

- Is there any vendor information for new equipment or replacement parts (e.g., burners)?

- How will this project affect the rest of the facility?

- What throughput/production level have we been at? (baseline)

- Where will throughput/production be at after the project? (projection/potential)

- Will we go over any permit limits?

Even with all the relevant information (back to the black and white thought) you may still want to request a determination from your friendly neighborhood permit agency to make sure you are on the right track with respect to the right permitting path (or whether you need a permit modification at all). Regardless of what the agency might say, liability regarding air permitting decisions (permit or no permit) falls on the facility.

Summary

Air permitting efforts can require a significant amount of information and resources and depending on your permitting agency’s requirements and the significance of the project air emissions impacts, it can take quite a bit of time before a final permit is issued and you can begin construction of your project. Therefore, it is best to engage your favorite air quality expert as early in the process as possible. Also note that a project that can be approved quickly in one state might take a long time in another state because public review, and possibly dispersion modeling, is required for a permit modification. Effective communication and input from all stakeholders is critical to preparing a technically sound and complete evaluation (and permit application, if needed). Also remember to tell your air permitting team if something changes with the project so they can address the change as needed. If you have any questions, please reach out!

The Clean Water Act Turns 50!

Introduction

In the summer of 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio had an oil slick significant enough to catch fire when sparks from a nearby train ignited the oil. Since 1868, this was the 13th time the Cuyahoga River had caught fire, but the first time that the blaze caught national attention. The Cuyahoga River and its history of pollution ultimately led to Congress passing the Clean Water Act (CWA) in October 1972.

Fast-forward to today, the CWA is turning 50! The United States (U.S.) Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) is currently celebrating by touring some iconic U.S. waterways, including the Florida Everglades, Chesapeake Bay, the Great Lakes, the Cuyahoga River, and the San Francisco Bay. Read on to find out what the CWA has accomplished over five decades.

History

Long before the CWA, the first U.S. law addressing water pollution was the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948. For 24 years, public awareness and concern for water pollution kept increasing until the Federal Water Pollution Control Act was revised and amended in 1972, becoming the CWA. The CWA establishes regulatory structure for discharges of pollutants into U.S. waters and quality standards for surface waters. The amendments made in 1972 kickstarted five decades of pollution prevention and have vastly improved wastewater and stormwater infrastructure.

The CWA gave U.S. EPA the authority to implement pollution control programs and established responsibility in each state to implement Water Quality Standards Programs (WQS). So far, the U.S. EPA has set wastewater standards for industry, has developed national water quality criteria recommendations for surface waters, and has made it unlawful to discharge any pollutant from a point source into navigable waters without a permit. The CWA is organized into sections, including but not limited to:

- Section 308 – Inspections, Monitoring, Entry

- Section 309 – Federal Enforcement Authority

- Section 401 – State and Tribal Certification of Water Quality

- Section 402 – National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System

- Section 403 – Ocean Discharge Criteria

- Section 404 – Discharges of Dredge or Fill Material

The success of the CWA is thanks to collaboration between Federal, state, local, and tribal governments — plus industry, agriculture, and non-profit organizations.

What to Remember

- Since the CWA was passed, the percentage of U.S. waterways deemed “fishable or swimmable” has increased from 40% to 60%.

- 47 states and one territory are authorized to implement NPDES. The states or territories with no NPDES program authorization are American Samoa, District of Columbia, Guam, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Northern Mariana Islands, and Puerto Rico. EPA is the permitting authority for states and territories that do not have authorization.

- The CWA has successfully reduced point source pollution in the United States. “Point source” pollution is pollution from identifiable sources, such as water treatment plants and industry.

- “Nonpoint source” pollution, or runoff pollution that flows through farmland and across industry facilities and city streets, inadvertently transports pollutants into our waterways and remains a significant challenge in the U.S.

- The U.S. EPA maintains an Office of Water (OW) that works to ensure that drinking water is safe, that oceans, watersheds, and ecosystems are restored and maintained, and that water sources are safe for human recreation and use.

- The U.S. EPA also sponsors the Watershed Academy that provides training on all things CWA, including professional learning modules, webcasts, publications, and youth resources.

Looking Ahead

For clean and safe U.S. waterways, there will always be progress to be made. The U.S. EPA is currently planning our next 50 years of clean water. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law established in 2022 has started the next 50 years on a high note with a $12.7 billion grant to the Clean Water State Revolving Fund.

ALL4 Water Quality Support

ALL4’s Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) Practice provides several services in water quality and water resources:

- Stormwater Permitting and Support

- National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permitting and Support

- Facility Compliance

- Spill Prevention, Control and Countermeasure (SPCC) Plans

- Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plans (SWPPP)

- Facility Response Plans (FRP)

- State-Specific Plans

- Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTW) Authorizations

- Water Resources

Q&A with Paul Hagerty, Directing Consultant

Q&A with Paul Hagerty, Directing Consultant

Q: What are your thoughts on the CWA?

A: It would be difficult for anyone to deny the obvious water quality achievements that have resulted from implementation of the Clean Water Act in 1972. No more rivers on fire, no more unfettered discharge of pollutants and no more treating surface water as a disposal point as opposed to a critical natural resource.

Q: How has the CWA adapted and matured since 1972?

A: In ALL4’s opinion, very nicely! The CWA was originally focused on point source discharges (e.g., wastewater) but has adapted over the years to include non-point discharges (e.g., stormwater runoff added in 1987 amendments), facility response planning (e.g., SPCC Plans, OPA90) and the continuous confirmation and modification to various water quality criteria (e.g., impaired waters, TMDLs).

Q: What do you see in the next few years regarding the CWA?

A: There are numerous items in front of U.S. EPA regarding clean water, including emerging contaminants (e.g., PFAS, microplastics), expansion of the SPCC requirements beyond just oil, the ever-changing definition of Waters of the U.S. and the challenges associated with water scarcity and water rights.

If you have any questions or are looking for support, please reach out to ALL4’s EHS Practice Director, Heather Brinkerhoff, CSP at hbrinkerhoff@all4inc.com or 571.325.0502 x512.

Louisiana Court Denies Air Permits for a Greenfield Plastics Complex on Clean Air Act and Environmental Justice Grounds: What are the implications?

On September 12, 2022, a Louisiana court rejected 14 air permits for a new plastics manufacturing complex to be developed by Formosa Plastics Group (Formosa). The nearly $10 billion complex, known as the “Sunshine Project,” would include 10 chemical manufacturing plants and supporting facilities spanning over 2000 acres. In the decision by Judge Trudy White in the case of Rise St. James, et al. v. Louisiana DEQ, the judge sided with the petitioners and rejected the permits on three grounds:

- That Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) violated the mandate of the Clean Air Act (CAA) by allowing the use of Significant Impact Levels (SILs) to demonstrate that the facility would not cause or contribute to a violation of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) or Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) class II increments.

- That LDEQ did not consider the cumulative impacts of the emissions of air toxics from not only the new complex, but also the emissions from other nearby facilities.

- The court also rejected as false LEDQ’s conclusion in its Environmental Justice (EJ) analysis that the nearby community, which is predominantly minority, would not be disproportionately affected by air pollution.

These three issues all have potential ramifications that are much more far reaching than just this individual case. This article takes a look at each and discusses how they might impact permitting of facilities in the future.

Clean Air Act “Cause or Contribute” Mandate

Possibly the most important of the three factors in the decision is the ruling that LDEQ wrongly determined that it could use the SILs to determine whether the proposed facility would cause or contribute to an exceedance of the relevant air standards. The key issue, one which has been the subject of debate for many years, is the definition of “contribute.” The SILs, de minimis thresholds set well below the air quality standards, have long been used to show that a project will not significantly contribute to air quality issues or that the project is not culpable for causing or contributing to an air quality standard exceedance; if the impacts from a project are below the SILs, it is concluded that the project will not have a significant impact on air quality, or cause or contribute to a NAAQS or PSD increment violation. SILs are also often used to determine which subset of a large receptor grid in a modeling exercise where there is any potential for a facility to cause or contribute to a standards violation at all. This SIL analysis assists in simplifying the process of determining which nearby facilities should be included in any cumulative modeling exercise, an important step because many states have poor databases of off-site sources that erroneously estimate their true potential impacts. Because of these issues and problems with off-site source characteristics, it is not uncommon for these off-site sources to have model-predicted impacts that exceed the standards when during normal refined modeling they would not. Demonstrating that a project’s contribution to such an exceedance is below the applicable SIL has long been the accepted method used to show the project does not significantly contribute to such an exceedance.

The basis for the court’s denial on these grounds comes from a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia rejecting a U.S. EPA SIL for PM2.5 in 2013. This ruling at the time vacated the PM2.5 SILs but did not reject the concept of the use of SILs as a whole, leading to the eventual creation of new U.S. EPA SIL guidance for PM2.5 (and ozone) in 2018. LDEQ used the 2018 guidance that allows the use of SILs. That 2018 guidance was also challenged in another lawsuit, but the D. C. Circuit held that the guidance was not a final action and therefore was not subject to litigation, thus leaving it up to the courts to assess whether the use of SILs was appropriate in permitting actions on a case-by-case basis. This decision is the basis for this denial.

Cumulative Impacts of Air Toxics

The second grounds for denial were that the permits allowed “excess air toxics,” specifically citing benzene and ethylene oxide (EtO). Additionally, the court noted that LDEQ did not conduct a cumulative impact analysis of not only the toxics emissions of the proposed facility but also the existing nearby facilities around the project site before concluding that they “together with those of nearby sources . . . would not allow for air quality impacts that could adversely affect human health or the environment.” The court again sided with the petitioners and found that statement to be false. The LDEQ Toxic Air Pollutants (TAPs) program, while it does require air dispersion modeling for non-criteria pollutants, does not require that nearby facilities also be included in the modeling. This is consistent with state toxics programs all across the United States: those that do require modeling rarely, if ever, require offsite sources to be included.

Environmental Justice

Finally, the court found that LDEQ’s conclusion in its EJ analysis that the nearby community is not disproportionately affected by air pollution was “…arbitrary and capricious.” The subject of EJ is on the one hand the highest profile (along with climate change) element of the Biden administration’s environmental agenda, but on the other is the least concrete in the sense that most states have no specific requirements around EJ in their permitting rules other than perhaps a policy statement that says that EJ must be considered in issuing permits near overburdened communities. In this specific case, while LDEQ concluded that “residents of the community closest to the (Formosa) complex do not bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial operations, the EJSCREEN analysis of the area performed by both LDEQ and the petitioners suggests it is, even though U.S. EPA has regularly stated that the tool is a screening tool and should not be used to determine whether a community is or isn’t overburdened. The petitioners’ and ALL4’s EJSCREEN review of the area show that numerous EJ Indexes are over the 80th percentile, the line that many agencies including U.S. EPA often use for such determinations (again, even though the documentation says you shouldn’t). LDEQ did not dispute the demographics shown by EJSCREEN in their decision but argued that the information in the tool does not reflect substantial reductions in emissions that have occurred since the information was published in 2014. The court reacted to this assertion by noting that the LDEQ ignored the situation in the immediate community by quantifying emission reductions in an area of 27 miles or 100 miles, depending on the pollutant, from the community in its assessment. Regardless of LDEQ’s decision, the EJ evaluation is further complicated because there is no specific regulation that says what would need to be done to mitigate or prevent additional levels of burden on an overburdened community in Louisiana’s, or federal, law.

What’s next?

On September 27, 2022, LDEQ and Formosa announced that they would appeal the court’s ruling, the chief argument being that the agency and Formosa followed all required agency and U.S. EPA procedures in issuing the permits. Regardless of how the appeal plays out, it appears that this project, which has been the subject of years of litigation already, will not be getting out of the courts any time soon.

What does the decision mean to permit applicants?

Each of the grounds for denial might have long term impacts on permitting actions across the United States. The potentially most impactful, in my opinion, is the denial of the use of the SILs in the cause and contribute analysis. Not only has this approach been standard practice for decades, but the denial of the use of SILs based on the grounds of the 2013 court decision leaves open the door for the potential denial of the use of SILs at all. Taken to an extreme, this could mean that a project might be required to execute cumulative modeling for every criteria pollutant regardless of how limited the increase in emissions from a project was, leading to a large increase in the permitting effort and agency review requirements with little or no real benefit. On the other hand, the 2013 lawsuit found that the validity of use of the SILs was left to the court’s discretion on a case-by-case basis, which could mean that this single decision is not likely to lead to an across-the-board end to the use of SILs. It does, however, give those opposing specific permit applications another legal decision to cite in their complaints, and ALL4 already has first-hand experience with a non-government organization citing this case in a permit appeal.

The denial on the grounds that LDEQ did not require cumulative modeling of toxics emissions is less onerous immediately: unless a state decided to revise its toxics program guidance to make such cumulative assessments a requirement, it seems unlikely that a court would be able to deny a permit solely on these grounds due to a lack of active regulations or laws that require it. However, we continue to await U.S. EPA’s guidance on cumulative impact assessments around permit actions located near overburdened communities. Stay tuned for more on this guidance as it is likely that it may include not only modeling requirements for toxics that include multiple facilities, but also a cumulative assessment of the impacts of several toxics to determine their combined impacts.

Finally, the denial on the grounds that the project would adversely affect an overburdened community is a continuation of activity we’re seeing in several permitting cases, where additional requirements or delays, or outright denials are occurring on EJ grounds when there are not specific requirements in the reviewing agency’s permitting rules. These cases have begun to trigger U.S. EPA review of state’s permitting rules under the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s Title VI provisions that state that no government agency may undertake an action that would disproportionately impact an overburdened community; the current investigation of Michigan’s permitting rules being a prime example. Additionally, back in August the U. S. EPA’s External Civil Right Compliance Office (ECRCO) published its Interim Environmental Justice and Civil Rights in Permitting FAQ, which provides details on how permitters should assess cumulative impacts and provides options for assessing the EJ impact of a project and potentially denying a permit under Civil Rights law even if it meets all other environmental requirements. The Formosa case is an example of how this concept might be used by the courts.

If you have concerns about the potential implications of this court decision and you’d like to discuss them, feel free to contact your ALL4 Project Manager or Rich Hamel. We’ll continue to monitor this case and others like it for their potential impact on permitting in the future. We can also help you evaluate permitting risks from EJ concerns to regulatory issues and assist in developing a strategy to make the permitting of your project as efficient as possible.

ECHO and ECHO Notify: Do you know what data is out there?

With different industries continuing to either expand their current facilities or build new facilities, public awareness and scrutiny has increased dramatically over the past few years. The public has started looking into different factors associated with facilities – including a facility’s location (and its associated Environmental Justice Index) and its enforcement and compliance history. As data becomes more publicly available, facilities will want to ensure that the data is as correct as possible to ensure the public is getting the most accurate image of the site in question. It also is a good basis of review to understand what kind of data is out there, and how can be used in different manners.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) publishes enforcement and compliance history for regulated facilities across the nation at their Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) webpage. ECHO provides permit, inspection, violation of environmental regulations, and enforcement action information for over one million EPA-regulated facilities. ECHO is available for public use, and users can register for email notifications for changes to the ECHO data via ECHO Notify. This article will provide information on how to use the ECHO webpage, what data is publicly available, how to sign up for ECHO notify, and guidance on updating any data related to your facility that may be inaccurate in the ECHO webpage. The U.S. EPA recently issued a press release announcing the updates associated with the Environmental Justice metrics and Benzene Fenceline Monitoring Dashboard for ECHO that are discussed below.

ECHO Search Tool

The ECHO database provides three-year compliance data and five-year inspection and enforcement history associated with Clean Air Act (CAA) stationary sources, Clean Water Act (CWA) permitted dischargers, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) hazardous waste handlers, and Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) public water systems. There are seven tabs to choose from on the ECHO website homepage. To search for data associated with a location or facility, the user can select either “Quick Search” or “Search Options.” The user can input a general location or facility specific information in “Quick Search,” and a more specialized search can be conducted using “Search Options.” The user has the option to specify media programs, geographic locations, community information, facility characteristics, enforcement and compliance data, environmental conditions, and pollutant information in “Search Options.” Upon conducting the search, an interactive map and data table are provided that summarize all the different applicable facilities associated with the search conducted. The user can add a layer summarizing Environmental Justice (EJ) information associated with a facility once it has been selected from the interactive map. The user can select “Add EJ Summary Map” at the top of the map to enable the EJSCREEN layer. The EJSCREEN option provides information associated with EJ indexes including, but not limited to, cancer risk, respiratory indexes, and Particulate Matter2.5 and ozone exposure information for the selected facility. This will allow the user to assess the sensitivity of the area being reviewed and can provide the user with EJ resources to help better navigate that arena.

ECHO Detailed Facility Report

To obtain a Detailed Facility Report from the map that provides details on the enforcement and compliance history of a facility, the user can select the chosen facility from the Facility Search Results page. The Detailed Facility Report allows the user to choose the media of interest (Air, Water, Hazardous Waste, or Drinking Water) as well as the Compliance History Timeframe (Monthly vs Quarterly). A summary of the Enforcement and Compliance History of the facility is provided in the report. The user also has the option to select other regulatory reports by selecting one of the related reports or other regulatory reports options on that page. The page also provides details associated with the facility characteristics and information, the compliance monitoring history and summary data, formal/informal enforcement actions, environmental conditions, toxic release inventory (TRI) data, and EJSCREEN EJ Indexes for the facility.

Reporting Errors

Upon reviewing the detailed summary report, the user can choose to report an error if needed. The user can report two types of errors. Data errors are associated with yellow error reporting icons next to applicable rows, and the icon must be selected to report a suspected data error. If the error is not associated with a line item with a yellow reporting icon, then a general error may be reported. To report an error, the user must navigate to the top right-hand corner of the Detailed Facility Report and select the “Report Data Error” button. Then, the user can either select a yellow reporting icon from the report or click the “Report General Error” button. Both options require the user to submit their personal contact information prior to providing their comment on the error. Once the error has been submitted, it will be entered into the U.S. EPA’s Integrated Error Correction Process and the appropriate Regional, State, or Local Steward will review the comment and make the appropriate changes. Errors can similarly be reported in all applicable charts and tabs from the ECHO database.

ECHO Notify

The user can sign up for ECHO Notify in the “Search Options” tool to receive email notifications of changes to enforcement and compliance data in ECHO tailored to an area of interest or for specific facilities. To access ECHO Notify, a login.gov account must be created by navigating to the top login link on the ECHO homepage. Once an account has been created, the ECHO Notify option can be selected in the “Search Options” tool, and the user can select the specific items they would like to receive notifications on, selecting specific locations/facilities, media, and types of enforcement/compliance actions. The bottom of the subscription page includes descriptions of the programs and terms being selected in this process. The email the user receives will include the time-period associated with the activities being reported, a high-level summary of the requested information, as well as links to receive more detailed information of the violations/enforcement actions being provided.

Trends (including the Benzene Fenceline Monitoring Dashboard updates)

The ECHO webpage also provides the option to “Analyze Trends” from the home page to review visualizations and performance trend tools including U.S. EPA/State Comparative Maps, a Data Visualization Gallery, and a Water Pollution Loading Tool. These three tools are briefly described in this paragraph, but there are additional tools under that section to explore compliance and enforcement data. The Comparative Maps tool allows the user to filter data by media, type of facility, and type of information requested (e.g., type of inspection/violation/penalties etc.). Once the user has filtered the data, they can select the state of interest. Clicking on the state provides a short summary of all activities in the state, and a state specific ECHO Dashboard or a National ECHO Dashboard can be selected to view the summary of trends for each criterion over time. The Data Visualization Gallery provides compliance-related dashboards and maps such as the Benzene Fenceline Monitoring Dashboard, which is a tool that reports benzene concentrations monitored by petroleum refineries since 2015. Users are able to view the data in maps and utilize the information for more detailed analyses of the facilities. The Water Pollution Loading Tool calculates and reports facility pollutant discharges by year or by monitoring period.

U.S. EPA Cases

The ECHO Homepage also allows users to find specific federal administrative and judicial enforcement actions by either searching by U.S. EPA case name or case number. The ECHO website also provides a News tab and allows the user to sign up for news notifications including updates to tools on the website, webinars, and enforcement news and actions set by the U.S. EPA.

Conclusion

With all enforcement, compliance, and EJ data available for public viewing, facilities are subject to more questions and commentary from the public. Understanding what data is out there and ensuring its accuracy can inform decisions facilities make moving forward and shape communication with the public. ALL4 is happy to provide guidance on the data and can help our clients make optimal decisions about their facility and industry growth and advise on mitigation strategies for any scrutiny that may arise from the publicly available data. For any questions or guidance on this matter, please contact me via email at relafifi@all4inc.com.

Universal Waste Series – Common Mistakes Managing Waste Batteries

This article is the second in a series of 4 the Record articles providing common mistakes and best practices to maintain compliance with universal waste regulations.

Universal waste regulations allow a universal waste generator to not count the designated waste towards their hazardous waste generator status as long as they comply with Chapter 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) §273. Handlers of universal waste can be classified as a small quantity handler, accumulates < 5,000 kg of universal waste at any one time, or a large quantity handler, accumulates > 5,000 kg of universal waste at any one time. A large quantity handler of universal waste must notify the Regional Administrator or State Agency where the state has primacy before exceeding the 5,000 kg accumulation storage limit to be issued a United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) identification number under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Subtitle C program.

The universal waste standards streamline the hazardous waste management standards for wastes that are commonly generated. There are three intended outcomes from the streamlined regulations according to the U.S. EPA website:

- Promote the collection and recycling of universal waste

- Ease the regulatory burden on retail stores and other generators that wish to collect these wastes and transporters of these wastes

- Encourage the development of municipal and commercial programs to reduce the quantity of these wastes going to municipal solid waste landfills or combustors

There are general requirements to be followed by all universal waste generators for every type of universal waste. For more information about EPA’s request for information on the development of best practices for the collection of batteries to be recycled, voluntary battery labeling guidelines, and examples of proposed best practices, read our other article Collecting and Storing Waste Batteries: Best Practices.

General universal waste management requirements

- One-year storage limit for universal waste accumulation

- Universal waste must be stored in structurally sound containers that are compatible with the waste and prevent breakage, spillage, or damage

- Universal waste containers must contain a label containing the phrases “Universal Waste” and the specific universal waste type. The start date of universal waste accumulation also needs to be included on the label

- Employees must be trained on applicable waste handling and emergency procedures

- Universal waste releases must be immediately contained

- Universal waste that meets the definition of hazardous materials per the U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S DOT) must contain the proper hazardous materials label and proper shipping paperwork per 49 CFR 172. U.S DOT hazardous material training must also be completed by any employee involved in the transportation of hazardous materials

- Track and maintain records of all universal waste shipments

- Universal waste must be sent to a universal waste destination facility

How are batteries defined?

In 40 CFR §273.9, batteries are defined as “a device consisting of one or more electrically connected electrochemical cells which is designed to receive, store, and deliver electric energy. An electrochemical cell is a system consisting of an anode, cathode, and an electrolyte, plus such connections (electrical and mechanical) as may be needed to allow the cell to deliver or receive electrical energy. The term battery also includes an intact, unbroken battery from which the electrolyte has been removed.” A used battery becomes a waste when it is discarded, and an unused battery become a waste once it is determined to be discarded.

Common battery chemistries:

- Alkaline

- Carbon zinc

- Lead acid

- Lithium & lithium-ion

- Mercury oxide

- Nickel cadmium

- Nickel metal hydride

- Silver oxide

The chemistry for many batteries will be provided using the elemental name on the battery label (e.g., Pb for lead). Voltage will be commonly provided on the battery label with a numeric value and the capital letter “V” for voltage (e.g., 12V). Some batteries will also include the watt hours on the battery label; watt hours will be provided as a numeric value with the letters “Wh” (e.g., 600Wh). Management requirements for waste batteries can vary by voltage and chemistry and being able to properly identify the chemistry and voltage of waste batteries is imperative.

What are common waste batteries management mistakes?

- Not having a dedicated and commonly known storage area for universal waste accumulation

- Exceeding the one-year storage limit for waste battery accumulation

- Storing waste batteries outside of a storage container

- Not having available waste battery containers near common points of generation (e.g., maintenance shops)

- Failing to label or appropriately label storage containers (using improper labels or not including the accumulation start date) for waste batteries

- Failing to keep containers storing waste batteries completely sealed unless waste batteries are being added to the container

- Using containers to store or ship waste batteries that are not compatible with the contents of the battery or approved by U.S DOT

- Handling leaking or corroded waste batteries without proper PPE, or in a manner that increases the likelihood that hazardous constituents are released to the environment

- Bagging or taping waste batteries together

- Storing waste batteries with incompatible chemistries together (e.g., alkaline and lead acid)

- Not managing waste batteries in accordance with applicable chemistry requirements (e.g., lithium-ion batteries)

- Shipping waste batteries without terminal protection that have U.S. DOT terminal protection requirements (e.g., lead acid batteries)

- Not completing the U.S. DOT hazardous material training if shipping universal waste that meets the definition of hazardous materials

How can I avoid the common waste batteries management mistakes?

- Pick a dedicated and commonly known universal waste storage area that allows for proper storage and is reasonably close to the source of universal waste generation.

- Include detailed instructions for proper waste batteries management in an annual universal waste training program. Also include the location of the universal waste storage area and which personnel are responsible for managing the universal waste program.

- Develop a Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) for waste batteries management and distribute to applicable personnel. Review and update the SOP routinely.

- Have a consistent inspection program that provides detailed corrective actions to employees responsible for waste batteries management.

- Know how to find battery chemistry and voltage information on each battery and manage waste batteries in accordance with applicable chemistry or voltage requirements.

- Minimize use of batteries with more stringent storage and shipping requirements.

- Fully understand the management, labeling, and shipping requirements for waste lithium-ion batteries.

- Keep track of supplies such as storage containers, labels, tape, or bags (terminal protection).

- Schedule pick-ups at intervals that avoid exceeding the one-year storage limit.

- Complete the U.S. DOT hazardous material training and complete the refresher training within the three-year requirement.

If you have any questions about universal waste or specifically waste batteries, please reach out to me at agolding@all4inc.com or Karen Thompson at kthompson@all4inc.com. ALL4 is here to answer your questions and assist your facility with all aspects of hazardous and universal waste management.

A Summary of Proposed Revisions to the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Rule

On June 21, 2022, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) proposed revisions to 40 CFR Part 98, the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Rule (GHGRR), with the comment period ending today, October 6th. The proposed GHGRR revisions include changes to 21 existing source-specific subparts, updates to the general provisions in Subpart A, and the addition of Subpart VV, Geological Sequestration of Carbon Dioxide with Enhanced Oil Recovery Using ISO 27916. The revisions fall into the following three general categories:

- Improvements to data quality

- Clarifications and corrections to rule language

- Streamlining and improving implementation of the GHGRR requirements

Additional information on each revision type is summarized below.

Data Quality Improvements

The following changes have been proposed with the intention of improving the quality of the data inputs and final results:

- Emission factors and emissions estimation methodologies have been updated to reflect a better understanding of emissions from several source categories.

- Pollutants and emissions sources for specific sectors have been added to address potential gaps in reporting.

- Reporting requirements have been refined and expanded to improve data quality and to collect more useful data to support verification of the reported data.

Rule Clarifications and Corrections

There have been several changes proposed with the intent of improving understanding of the GHGRR and its requirements. These include amendments to several subparts and clarification of definitions to clean up language that has resulted in reporting that is inconsistent with the rule requirements. Two examples of these types of changes include the following:

- Updating definitions of reported data elements that may be unclear and have historically been misread by reporters.

- Revising Subpart Y to resolve the potential discrepancy between the flare emission calculations at 40 CFR 98.253(b), which requires that all gas discharged through the flare stack must be included in the calculations except for pilot gas, and the requirements at 40 CFR 98.253(b)(1)(iii), which excludes startup, shutdown, and malfunction (SSM) events less than 500,000 standard cubic feet per day (scf/day) from equation Y-3.

Streamlining Requirements

The following changes have been proposed with the intention of streamlining and improving implementation of the GHGRR:

- The applicability criteria have been revised for three subparts to account for changes in usage of certain GHGs, or where the current applicability estimation methodology may overestimate emissions.

- Monitoring requirements have been revised in some instances where a less burdensome methodology is already allowed for similar emissions sources, or the frequency of data collection is not justified.

- Applicability provisions in some instances have been revised to reduce uncertainty regarding which calculation method should be used.

- Redundant reporting and recordkeeping requirements and inconsistencies that exist in the current rule have been removed.

- The frequency of reporting information that does not change on a frequent basis has been reduced.

The following subparts have been affected by the proposed revisions:

- Subpart A – General Provisions

- Subpart C – General Stationary Fuel Combustion Sources

- Subpart G – Ammonia Manufacturing

- Subpart H – Cement Production

- Subpart I – Electronics Manufacturing

- Subpart N – Glass Production

- Subpart P – Hydrogen Production

- Subpart Q – Iron and Steel Production

- Subpart S – Lime Manufacturing

- Subpart W – Petroleum and Natural Gas Systems

- Subpart X – Petrochemical Production

- Subpart Y – Petroleum Refineries

- Subpart BB – Silicon Carbide Production

- Subpart DD – Electrical Transmission and Distribution Equipment Use

- Subpart FF – Underground Coal Mines

- Subpart GG – Zinc Production

- Subpart HH – Municipal Solid Waste Landfills

- Subpart NN – Suppliers of Natural Gas and Natural Gas Liquids

- Subpart OO – Suppliers of Industrial Greenhouse Gases

- Subpart PP – Suppliers of Carbon Dioxide

- Subpart SS – Electrical Equipment Manufacturers or Refurbishment

- Subpart UU – Injection of Carbon Dioxide

- Subpart VV (new) – Geologic Sequestration of Carbon Dioxide with Enhanced Oil Recovery Using ISO 27916

In addition, U.S. EPA is requesting comment on future changes to the aluminum production source category, the expansion of certain other source categories, and the addition of new source categories that include the following:

- Energy consumption

- Ceramics production

- Calcium carbide production

- Glyoxal production

- Glyoxylic acid production

- Caprolactam production

- Coke calcining, and

- CO2 utilization

Finally, the U.S. EPA is proposing to establish and revise confidentiality determinations for existing, new, or revised data elements.

What do I need to do?

The original 60-day public comment period was set to end on August 22, 2022. However, on July 19th it was extended until October 6, 2022. U.S. EPA is planning to respond to comments and publish any amendments before the end of 2022 such that they would become effective on January 1, 2023. Reporters would be expected to review and understand the changes in their applicable subparts and implement them for the 2023 reporting year submittals that are due on April 1, 2024.

If you have questions about how the proposed GHGRR rule revisions could affect your facility’s program, or what your next steps should be once the rule is finalized, please reach out to me at cward@all4inc.com. ALL4 is monitoring all updates published by the U.S. EPA on this topic, and we are here to answer your questions and assist your facility with any aspects of GHGRR compliance.

Q&A with Paul Hagerty, Directing Consultant

Q&A with Paul Hagerty, Directing Consultant