Final Reconsideration Rules for Chemicals and Refineries

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) is finalizing changes to petroleum and chemical sector rules in response to petitions for reconsideration following recent risk and technology review (RTR) rulemakings. These rules include the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants for Ethylene Production (EMACT), Organic Liquids Distribution (Non-Gasoline) (OLD), Miscellaneous Organic Chemical Manufacturing (MON), and Petroleum Refineries source categories.

U.S. EPA issued a proposed reconsideration rule on April 27, 2023 and Administrator Regan signed the final rule on March 15, 2023. This article provides a summary of the significant changes to each rule as described in the pre-publication version of the final rule posted to U.S. EPA’s website.

Force Majeure Allowance Removed

First, U.S. EPA is removing the force majeure allowance from the atmospheric pressure relief device (PRD) release and emergency flaring work practices in the EMACT, MON, and Petroleum Refineries rules. These work practices include specific criteria defining what events constitute a violation of the standard. Previously, atmospheric PRD releases and emergency flaring resulting from a force majeure event (i.e., an event outside of the facility’s control) were not considered when determining whether a release or set of release events constituted a violation. Moving forward, force majeure events must be considered when determining whether a release qualifies as a violation under the work practice standards. In the preamble to the final rule, U.S. EPA states that the Agency will “continue to evaluate violations on a case-by-case basis and determine whether an enforcement action is appropriate.” U.S. EPA further indicates that sources may raise defenses to an enforcement action as part of court proceedings. In addition to removing the force majeure allowance, U.S. EPA is finalizing electronic reporting requirements for atmospheric PRD releases and emergency flaring events.

Storage Vessel Degassing and Maintenance Vent Requirements Clarified

For EMACT, OLD, and MON, U.S. EPA is finalizing work practice standards for storage vessel degassing. U.S. EPA did not include degassing standards in the proposed rules during the RTR process but promulgated work practices in the 2020 final rules. This resulted in a notice and comment issue. To address the notice and comment issue, U.S. EPA re-proposed the work practice standards in 2023. The standards allow storage vessels to vent to the atmosphere once liquids have been removed to the extent practicable and the vapor concentration inside the storage vessel is 10% of the lower explosive limit (LEL). U.S. EPA also addressed petitioners’ concerns that floating roof storage vessels could not meet the vapor concentration requirement without opening the storage vessel to attach temporary control devices. U.S. EPA is finalizing the degassing requirements as proposed, including an allowance for floating roof storage vessels to be opened in preparation for degassing. U.S. EPA is also providing two important clarifications in the preamble to the final rule: 1) emissions from breathing losses after landing a floating roof while preparing for degassing are not considered a bypass or a deviation of the standards, and 2) the MON and OLD overlap provisions for storage tanks do not apply to the new degassing standards (i.e., if a facility is using the overlap provisions under the MON or OLD, they are still required to comply with the degassing requirements).

Also, for EMACT, OLD, MON, and Petroleum Refineries, U.S. EPA is clarifying the use of the term LEL in context of storage vessel degassing and maintenance vent provisions. These rules previously required facilities to measure and reduce the LEL inside equipment and storage vessels prior to opening; however, commenters noted that LEL is a physical property and not something that can be altered by purging equipment. Thus, U.S. EPA is revising the rules to clarify the intent, i.e., that the vapor concentration inside the equipment or storage vessel is measured and compared to the LEL.

Ethylene Cracking Furnace Work Practices

Under EMACT, U.S. EPA is addressing work practices for ethylene cracking furnaces by finalizing a change that allows furnace operators to delay repair of burners until the next planned decoking operation or complete shutdown (whichever occurs first) if the repair cannot occur during normal operations. U.S. EPA is finalizing another change to the furnace work practices to allow furnace operators to wait to rectify isolation valve issues until after the furnace has been decoked if the operator determines that the furnace would be damaged if the repair was attempted before decoking and/or shut down of the furnace.

Heat Exchange Systems Monitoring

U.S. EPA is finalizing changes to heat exchange system monitoring in the MON by allowing the use of monitoring methods under 40 CFR § 63.104(b) in lieu of the Modified El Paso Method if 99% by weight or more of the organic compounds that could potentially leak into the cooling tower water are water soluble and have a Henry’s Law Constant of 5.0E-06 or less (at 25°C). With some qualifications, 40 CFR § 63.104(b) allows the use of any U.S. EPA-approved method listed in 40 CFR Part 136.

Ethylene Oxide Emissions

U.S. EPA is clarifying in the MON that sites are required to monitor the scrubber liquid-to-gas ratio, the scrubber liquid pH, and the temperature of the scrubber liquid (as opposed to “water”) entering the column if a scrubber with a reactant tank is used to control ethylene oxide emissions. If the scrubber does not use a reactant tank, the facility must establish site-specific operating parameters during the performance test to demonstrate ongoing compliance.

U.S. EPA is also finalizing revisions to allow calculations and site-specific data when determining the concentration of ethylene oxide in storage vessels.

Despite requests from commenters, the Agency is maintaining that delay of repair provisions are not available for pumps and connectors in ethylene oxide service, except in the instance that the equipment can be isolated from the process and it does not remain in ethylene oxide service.

Adsorbers

Under the MON, U.S. EPA is clarifying applicability for several provisions related to adsorbers that cannot be regenerated or that are regenerated off-site. The Agency is also requiring facilities to submit a supplement to the notification of compliance status (NOCS) to describe the adsorber characteristics as they relate to the initial and ongoing compliance demonstrations. The Agency is also finalizing updates to the recordkeeping requirements for these types of adsorbers to align with the design standard and monitoring requirements that were promulgated under the RTR. Also under the MON, U.S. EPA is finalizing the requirement to submit NOCS reports electronically.

Flares

In the Petroleum Refineries rule, U.S. EPA is finalizing requirements for pressure assisted flares. These are similar to the requirements promulgated for EMACT and MON. The Agency is also finalizing provisions to allow for the use of mass spectrometry to determine flare gas composition, along with clarifications on the associated quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) requirements.

Wrap-up

In addition to the revisions described above, U.S. EPA is promulgating changes to address typographical errors and other minor clarifications in each rule. With the exception the removal of the force majeure allowance and the changes outlined above for flares under the Petroleum Refineries rule, the revisions included in this rulemaking will be effective when the final rule is published in the Federal Register. The removal of the force majeure allowance and the flare amendments will come into effect 60 days following publication. Facilities should review the rules for changes affecting their operations. Please reach out to me or your ALL4 project manager with any questions on the new changes.

New Approved PFAS Testing Methods

As a follow up to our 2024 PFAS Look Ahead, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Water published Methods 1633 and 1621 in January. In the past, Method 537.1 has been modified to meet analytical needs. With the publication of these testing methods, the door has been opened for additional federal regulation of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

At present, a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) has been proposed to establish MCLs for six PFAS in drinking water: perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA [GenX]), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS).

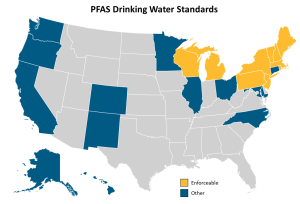

In the meantime, many states are taking the lead by setting their own drinking water standards and regulations. So far, ten states have enforceable standards (e.g., MCLs) for PFAS chemicals, and 13 others have adopted other standards such as guidance levels, notification levels, health advisories, or some combination of the three.

Methods for Industrial Wastewater & Stormwater

Method 1621

Worried about PFAS in your wastewater? The EPA’s Method 1621 can be a helpful first step. This method quickly and affordably screens for a broad range of organofluorine compounds at very low levels. PFAS are the most common sources of these compounds that are also found in pesticides and pharmaceuticals. While this method can’t tell you exactly which PFAS compounds or what quantities are present, it can identify samples with potentially problematic levels of organofluorines.

Think of Method 1621 as a red flag: if the screening shows high levels of organofluorines, it suggests further investigation might be needed. For a more detailed picture, specific analytical methods would be required to pinpoint the exact types and amounts of PFAS present.

In the field, 100-mL samples are collected in triplicate using high-density polyethylene or polypropylene bottles. Free-flowing wastewater is collected as grab samples or in refrigerated bottles using automated equipment. The pooled method detection limit (MDL) from the multi-laboratory validation study is 1.5 µg F–/L, and the minimum level of quantitation (ML) is 5.0 µg F–/L.

Method 1633

If results from your wastewater screening with Method 1621 indicate that you should dig deeper, the EPA’s Method 1633 has you covered: published in January 2024, this method tests for 40 PFAS analytes in eight different environmental matrices, including wastewater, surface water, groundwater, soil, biosolids, sediment, landfill leachate, and fish tissue. The method can be utilized for various applications, including for National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits.

The sampling procedure for Method 1633 differs significantly depending on the sample itself. For example, samples taken from free-flowing sources are collected as grab samples, while those from still waters must account for the enrichment of PFAS in the surface layer; leachate samples from landfills need only measure 100 mL due to the significant challenges they pose, while all other samples require 500 mL. The method detection limit (MDL) ranges from 0.32 to 9.59 ng/L for aqueous samples. Specific details can be found in the EPA Method 1633 January 2024 publication.

SW-846 Test Method 8327

The EPA’s Test Method 8327 can also be utilized to confirm the presence of PFAS in surface water, groundwater, and wastewater. This method is contained in the SW-846 Compendium, which is instrumental in compliance with Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) regulations. It accurately measures 24 PFAS analytes, 10 of which are primarily sulfonic acids.

Methods for Drinking Water

Method 537.1

In 2009, U.S. EPA published Method 537 to evaluate for 14 different PFAS in drinking water using solid-phase extraction (SPE) followed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). Updated in 2018, Method 537.1 now includes four additional PFAS for a total of 18 analytes and is approved to monitor PFAS during Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule 5 (UCMR5, 2023-2025) which measures 29 PFAS plus lithium. In this method, 250-mL drinking water samples are collected and combined with Trizma, a preservation reagent that eliminates free chlorine from the sample. The lowest concentration minimum reporting level (LCMRL) of this method ranges from 0.5 to 6.3 ng/L for various PFAS.

Method 533

Also utilized to evaluate drinking water, U.S. EPA published Method 533 in 2019, in addition to Method 537.1, to evaluate PFAS. This method places an emphasis on short chain PFAS (e.g., those whose carbon chains have a length between four and 12), captures 11 of these short chain analytes as well as 14 of the 18 PFAS tested by Method 537.1, and is also approved to monitor PFAS during UCMR5. Using Methods 537.1 and 533 in tandem, drinking water can be tested for a total of 29 PFAS. Although these two EPA Methods complement each other, they also differ significantly in several ways. An example is the addition of ammonium acetate to the collected drinking water samples. The LCMRL of this method ranges from 1.4 to 16 ng/L for various PFAS.

Looking Ahead

Comprehensive PFAS Testing Solutions for Water

The U.S. EPA offers various methods for analyzing PFAS in different water types, including drinking water, groundwater, surface water, and wastewater. This aligns with their PFAS Strategic Roadmap, which includes establishing MCLs for drinking water.

Uncertain about PFAS Testing Requirements or Methods?

Selecting the Right PFAS Test Method for Your Needs

Choosing the most suitable PFAS testing method is crucial for accurate and informative results. Here are some key factors to consider:

- Sample Type: The type of sample you’re analyzing (industrial wastewater, stormwater, drinking water, etc.) greatly influences the appropriate method. This blog post focuses on industrial wastewater and stormwater sampling.

- Specific PFAS Analytes: Are you interested in a broad screening of all potential PFAS or targeting specific PFAS compounds? Different methods cater to these needs.

- Detection Limits: How low of a concentration do you need to detect? This depends on your specific concerns and regulatory requirements.

ALL4 can help you make the critical decision on which test method best fits your situation.

Finding Certified Laboratories

Once you’ve identified a suitable method based on your sample type and needs, it’s essential to find a certified laboratory for analysis. ALL4 can assist you in this process by helping you:

- Match your project requirements with laboratories that hold the necessary certifications for your chosen PFAS testing method.

- Navigate the complexities of PFAS analysis and ensure you receive accurate and reliable results.

Sample Collection

The ubiquity of PFAS provides ample opportunity for cross-contamination in the sampling environment. Here are some possible sources of interference to consider:

- Materials & Equipment: Did you know that PFAS may still be present even if not listed on a safety data sheet? HPDE, polypropylene, silicone, and acetate have been proven to be most reliable for PFAS sampling, whereas glass is known to adsorb PFAS over extended periods of contact.

- Field Clothing: Do you have any clothes that were made to resist water, dirt, or stains? If so, they probably contain PFAS and are unsuitable for the sampling environment. Your best bet is to wear 100% cotton clothing.

- Personal Care Products: Items we use daily (e.g., cosmetics, deodorant, moisturizer, etc.) and during long periods outdoors (e.g., sunscreen, bug spray) can be detrimental to the sampling environment and should only be used in the staging area.

- Food Packaging: Pre-wrapped foods and snacks should be avoided altogether in the sampling environment if at all possible but can be handled or eaten in the staging area if necessary.

ALL4 can help you reduce the likelihood of contamination in your sampling environment by developing a project-specific quality assurance project plan (QAPP) and conducting an evaluation of your material inventory to ensure that any sampling you may conduct proceeds without cross-contamination.

If you’re unsure whether your state or facility needs PFAS testing, which method is most suitable for your situation, or require guidance on sampling and analysis strategies, contact our team at ALL4. Our experts, Madeline Statkewicz (mstatkewicz@all4inc.com), Tia Sova (tsova@all4inc.com), or Kyle Costello (kcostello@all4inc.com), can assist you.

D.C. Circuit Vacates U.S. EPA’s SSM SIP Call

On March 1, 2024, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia (D.C.) Circuit decided 2 to 1 to vacate the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (U.S. EPA’s) State Implementation Plan Call with respect to certain startup, shutdown, and malfunction provisions (SSM SIP Call). The SIP Call was vacated with respect to automatic exemptions, director’s discretion provisions, and certain affirmative defense provisions.

How did we get here?

When the 1970 Clean Air Act (CAA) Amendments were passed and the U.S. EPA was formed, they developed National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) and states were required to develop SIPs that protected those standards. Many states recognized that facilities often could not meet certain emissions standards during startup, shutdown and malfunctions, and put various provisions into their SIPs to address those scenarios. U.S. EPA approved these SIPs in the 1970s and 1980s, but U.S. EPA was petitioned by Sierra Club in 2011, who identified 39 SIPs that they believed contained SSM provisions that made the SIPs unlawful. U.S. EPA is allowed to “call” upon a state to revise a SIP if it makes a finding of “substantial inadequacy.” In 2015, U.S. EPA finalized its SSM SIP Call for 35 states and Washington D.C.

The SSM provisions of concern were:

- Automatic exemptions (e.g., provisions stating that a SIP emissions or opacity limit does not apply during periods of startup or shutdown or during a malfunction).

- Director’s discretion provisions (e.g., provisions that allow a facility to ask the state agency Director to determine that excess emissions during SSM events were not a violation).

- Overbroad enforcement discretion provisions (only one SIP, Tennessee’s, was called for this reason, as U.S. EPA thought that the provisions could be read to allow Tennessee officials to foreclose U.S. EPA enforcement actions and citizen suits).

- Affirmative defense provisions (where a state could prevent U.S. EPA and citizens from holding facilities liable for excess emissions during SSM).

Three sets of petitioners sought the court’s review of the SSM SIP Call: Texas and a coalition of Texas companies and trade groups, a group of 18 other states, and a group of industrial companies and organizations. When the Trump administration came into office, U.S. EPA asked the court to hold the case in abeyance as it reconsidered the SIP Call. During the four-year abeyance, U.S. EPA withdrew its SSM SIP Calls for Iowa, North Carolina, and Texas, leaving 16 states and the industry petitioners in the case. In November 2021, U.S. EPA reaffirmed the original SSM SIP Calls and asked the court to move forward. The case was argued in 2022.

What did the D.C. Circuit Court decide?

First, they evaluated U.S. EPA’s authority to make the SSM SIP Call. The D.C. Circuit determined that U.S. EPA did not have to show actual harm had occurred as a result of the offending provisions (i.e., that the SSM provisions were causing violations of the NAAQS), just that they had made a finding that something about the SIP was inconsistent with the requirements of the CAA. U.S. EPA had reasonably determined that a SIP provision could be understood to conflict with the CAA. The D.C. Circuit also found that U.S. EPA did not have to consider cost as part of its SIP Call (noting that the states could remedy their SIPs in a number of ways that could have differing costs and that balancing the benefits and burdens of a particular SIP revision was therefore best left to the states).

Second, the D.C. Circuit analyzed whether U.S. EPA correctly called the four specific categories of SSM provisions. U.S. EPA called the SIPs because they claimed the offending SSM provisions meant that the underlying standards did not meet the definition of “emissions limitation,” which the CAA defines as a requirement that limits emissions “on a continuous basis.” The CAA requires SIPs to include “enforceable emission limitations and other control measures, means, or techniques (including economic incentives such as fees, marketable permits, and auctions of emissions rights), as well as schedules and timetables for compliance, as may be necessary or appropriate to meet the applicable requirements of this chapter.” The court determined that when a standard is coupled with an automatic exemption or director’s discretion provision, even if it does not meet the definition of emissions limitation (which the court did not decide), that alone is not necessarily grounds for U.S. EPA to issue a SIP Call, because the SIP provisions may constitute “other control measures, means, or techniques” that can also be included in a SIP to meet CAA requirements. Therefore, U.S. EPA’s blanket call of automatic exemptions and director’s discretion provisions was set aside because the agency reasoned that every emissions restriction in a SIP had to be continuous to qualify as an emissions limitation, without explaining why that continuity is necessary or appropriate to meet CAA requirements.

With respect to the third category of SSM provisions, the court denied the petition to review the Tennessee SIP Call because the petitioners argued that U.S. EPA could not issue a SIP Call based on ambiguity, and the court rejected this argument. Finally, the D.C. Circuit examined two types of affirmative defense provisions. The first kind provides a complete affirmative defense to an action brought for non-compliance, and the court determined that those provisions were akin to automatic exemption provisions and vacated the SIP Call for those provisions. The second kind precludes certain remedies after a source has violated an emissions standard. The D.C. Circuit held that states cannot limit the relief that Congress empowered federal courts to grant for violations of emissions rules and denied the petition for review of the SIP Call for those types of affirmative defense provisions.

What does this mean?

This decision (which U.S. EPA still has time to attempt to appeal) only directly affects certain states. In Iowa, Texas, and North Carolina, U.S. EPA’s 2023 proposal to reinstate the SSM SIP Calls for those states presumably will have to be reconsidered and a revised rationale offered before SSM SIP Calls are re-issued. For the 16 remaining states that petitioned the court for review of the SSM SIP Call, they do not have to revise the SSM provisions in their SIPs except for the Tennessee provisions that can be read as being overly broad, and the states that have affirmative defense provisions that prohibit citizens and U.S. EPA from seeking certain types of relief (e.g., only monetary penalties) against sources that violate SIP standards. In states where the SIP has already been revised to address the SSM provisions that U.S. EPA called and has been approved by U.S. EPA, sources will be subject to those new provisions unless and until the SIP is revised and approved by U.S. EPA again. For more information about what SIP requirements apply in your state, reach out to your ALL4 project manager or Amy Marshall.

Amy Marshall would like to acknowledge and thank Russ Frye (who argued the case for industry petitioners) for reviewing and editing this article.

Louisiana Embraces Environmental Transparency: A Look at the New Voluntary Self-Audit Program

The state of Louisiana took a significant step towards environmental transparency and improved compliance with regulations for the implementation of its first-ever voluntary environmental self-audit program on December 20, 2023. The program is explained in detail as part of Vol. 49, No. 12 of the Louisiana Register (Starts on Page 2099). This program, established by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ), empowers businesses to proactively identify and address environmental violations, potentially lowering, and possibly eliminating civil penalties in the process. This article delves deeper into the details of the new program, exploring its benefits, and discussing potential considerations facilities should review before implementing the program.

Understanding Voluntary Environmental Self-Audits

Voluntary environmental self-audits are systematic reviews conducted by a business to assess its compliance with applicable environmental regulations. These audits involve examining operations, compliance documentation, and environmental management systems to identify potential violations or areas for improvement. Louisiana’s program is similar to both the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s (TCEQ) previously established Texas Audit Privilege Act and the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (U.S. EPA) Audit Policy. Both of these programs allow and outline requirements for environmental self-audits.

Key Features of Louisiana’s Self Audit Program

To better understand the new LDEQ self-audit program, a summary of major requirements and timelines are outlined below:

- Voluntary Participation: Businesses have the discretion to choose whether or not to participate in the program.

- Incentive for Disclosure: Upon disclosing violations discovered during the self-audit to the LDEQ, businesses may be eligible for reduced or even eliminated civil penalties, provided that violations meet the program’s disclosure conditions. This incentive encourages self-identification and rectification of environmental issues, fostering a more collaborative approach to environmental compliance.

- Audit Review Fee: Businesses are required to pay a fee for the LDEQ to review the self-audit report and any proposed corrective actions. The fee structure includes a minimum of $1,500 and additional charges based on hourly rates and associated costs of LDEQ as specified in Louisiana Revised Statutes (LA R.S.) 30:2044(C).

- Specific Requirements: The program outlines specific requirements for conducting and reporting on the self-audit, including:

- Initiation: The audit must be conducted by a qualified environmental professional once a Notice of Audit is given to LDEQ (notice forms and submission procedures will be available on LDEQ’s website).

- Disclosure: The program mandates a comprehensive audit scope that covers all applicable environmental regulations relevant to the business’s operations. Violations must be disclosed to LDEQ within 45 days of discovery (disclosure forms and submission procedures will also be available on LDEQ’s website).

- Extensions: Should a facility not complete their self-audit within six months of their original notice, they can request a 30-day extension from LDEQ with reasonable justification.

- Corrective Actions: Corrective actions taken as a result of audit findings must be completed within 90 days of the initial violation discovery. Any timeline longer than 90 days must be approved by LDEQ via writing.

- Audit Report: Once the audit and all corrective actions are complete, an audit report must be written and sent to LDEQ including the notice of audit, violation disclosure, and proof of corrective action.

Benefits of the Program:

The potential for reduced or eliminated civil penalties encourages self-disclosure and corrective action, ultimately leading to a more cost-effective approach to environmental compliance for businesses. As the program currently stands, there are nine separate conditions that must be met to be eligible for 100% penalty reduction including but not limited too correctly following all self-audit rules for notification and disclosure outlined above, and making sure the violation observed has not previously occurred at the Facility in the last three years. For more information and the full list of these conditions please see the Vol. 49, No. 12 of the Louisiana Register (Starts on Page 2101). Overall, the program fosters a more collaborative relationship between businesses and the LDEQ, promoting open communication and problem-solving regarding environmental compliance through proactively identifying and addressing environmental issues.

Potential Considerations

When reviewing or implementing the LDEQ self-audit program, facilities should consider the following:

- Cost: Facilities should evaluate the cost of performing a self-audit versus the cost of potential noncompliance fines and/or the attorney fees required to navigate noncompliance.

- Reliance on Self-Disclosure: The program’s effectiveness relies heavily on the accuracy and completeness of self-disclosed information. Facilities using this program should pay careful attention during the self-audit, notification, and report submission to avoid potential incomplete disclosures or notifications.

- Limited Scope: The program focuses solely on civil penalties, and criminal sanctions for environmental violations remain unaffected.

- Excluded Violations: The following environmental violations are excluded from relief under the self-audit program:

- Those that result in serious harm or substantial/imminent danger to the environment or public health.

- Those discovered by the LDEQ or U.S. EPA, prior to disclosure.

- Those detected through monitoring, sampling, or auditing procedures that are already required based on an order, regulation, permit, or consents agreement.

- Those that are deliberate or closely related to a violation in the last three years subject to 40 CFR Part 68 and LAC 33: III.5901 (Chemical Accident Prevention).

Looking Forward

Like many states that have already implemented similar programs, facilities in Louisiana can now start planning and implementing this new self-audit program that allows for self-disclosure of environmental violations and potential reduction of civil penalties related. The implementation of Louisiana’s voluntary environmental self-audit program marks a significant step towards promoting environmental responsibility and fostering a culture of compliance within the state.

ALL4 Can Help!

ALL4’s diverse roster of environmental professionals has not only worked with similar self-audit programs in other states, such as Texas, but has performed environmental audits and understand environmental audit processes for all disciplines under the Environment, Health, and Safety umbrella. If you have any questions about LDEQ’s new self-audit program or want to learn more about ALL4’s audit support capabilities, please reach out to Andrew Hebert at ahebert@all4inc.com.

Enforcement Alert – BWON

In February 2024, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Office of Civil Enforcement issued a long expected Enforcement Alert targeting facilities subject to 40 CFR Part 61 Subpart FF – National Emission Standard for Benzene Waste Operations (BWON). BWON applies to chemical manufacturing plants, coke by-product recovery plants, petroleum refineries, and hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities. The Enforcement Alert specifically calls out BWON compliance concerns at petroleum refineries and ethylene plants based on a series of inspections and reviews that have been completed by U.S. EPA. An explanation of U.S. EPA’s specific BWON compliance concerns can be found in the Enforcement Alert.

Background

Facilities potentially subject to BWON requirements must calculate total annual benzene (TAB) emissions from the facility using the procedures identified in 40 CFR §61.355. Requirements are then triggered based on three basic categories: TAB equal to or greater than 10 megagrams per year (Mg/yr), TAB is less than 10 Mg/yr but greater than 1 Mg/yr, or TAB less than 1 Mg/yr.

Petroleum refineries subject to BWON may also be subject to 40 CFR Part 60 Subpart QQQ – Standards of Performance for VOC emissions From Petroleum Refinery Wastewater Systems (NSPS QQQ). The subpart regulates individual drain systems and oil-water separators at refineries that have been constructed, modified, or reconstructed after May 4, 1987. EPA’s Subpart QQQ compliance concerns center around proper water seals, visual inspections, timely repairs, and maintenance of sewer lines.

The seriousness of these violations can be illustrated in a May 2023 Consent Decree resulting from a civil case, The United States of America and The State of Indiane v. BP Products North America, Inc. (found here). The recent Consent Decree (CD) includes a stipulated penalty demand of over $8.5 million and civil penalties of over $30 million. The CD also includes a supplemental environmental project and significant investment in operational controls. These penalties are for violations of BWON, NSPS QQQ, and the NSPS and NESHAP general provisions at 40 CFR part 60, Subpart A and 40 CFR Part 61, Subpart A. Additional Consent Decrees are currently in negotiation resulting from recent U.S. EPA inspections.

What action should you take?

ALL4 urges industries that are potentially subject to BWON and/or NSPS QQQ to carefully review the Enforcement Alert and the recent Consent Decree. Facilities should consider auditing their BWON and NSPS QQQ activities to ensure compliance with these regulations.

ALL4 will be hosting a Webinar on June 19th on BWON and QQQ with topics including background on the enforcement alert, what facilities can expect during an inspection, what facilities can do to prepare for an inspection, etc. More information and how to register can be found here. ALL4’s team of experienced engineers and scientists stand ready to assist clients with all of your EHS needs. If you have questions or would like to discuss your facility’s BWON program, contact Bob Kuklentz at rkuklentz@all4inc.com.

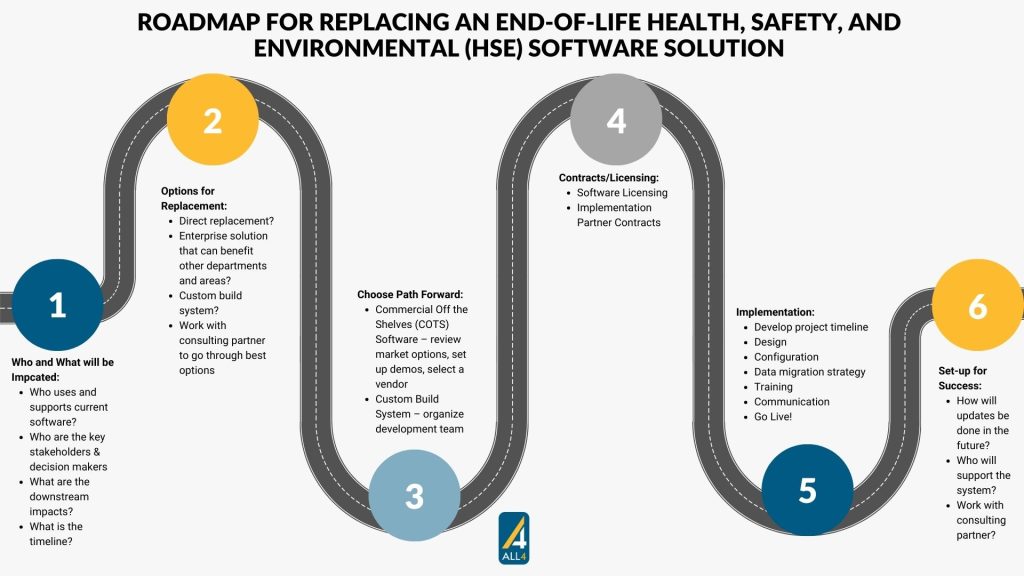

Roadmap for Replacing an End-of-Life Health, Safety, and Environmental (HSE) Software Solution

Have you been told your Health, Safety, and Environmental (HSE) software will no longer be supported? As software companies continue to evolve, so do their solutions, which leads to the inevitable emergence of new programs and the departure of the old. While losing a working solution is never ideal, it can be a great opportunity to improve existing processes.

Once you have heard a software tool will be discontinued, it is important to start developing an exit strategy to give your team plenty of time to plan the next steps, avoid missing regulatory reporting deadlines, reduce disruption to your user base, and to ensure that the company continues to stay in compliance.

If you have found yourself having to replace an established software tool, here is a high-level roadmap that your team can leverage to help make your company’s transition as stress-free as possible.

Identify Who and What will be Impacted

One of the key steps in effectively replacing an HSE software solution and avoiding unwanted roadblocks is identifying who and what will be impacted, and when it will take place.

- Who is using the current system and will be impacted by the change (i.e., business areas, departments, specific country locations)?

- Identify key stakeholders and decision makers and get them involved. This is especially important when considering what budget discussions and approvals may need to be considered.

- Who supports the current system (i.e., IT, EHS, consultants)? Start having discussions with these teams and keep them part of the conversation going forward.

- What other upstream or downstream systems are currently being used (i.e., integrations, Power BI) that may be impacted?

- When will the software stop being supported, and when would a new solution need to be in place? This is a good time to start drafting out a timeline and identify drivers such as regulatory reporting dates, the date for sunsetting the previous software, budget approvals, internal resource capacity/capabilities, etc.

- Does the company have specific security-related IT policies that could impact moving forward such as single sign-on or specific auditability requirements?

Identify Options for Replacement

ALL4 can help take out some of the guesswork of this stage. As a professional Digital Solutions Practice that has done many projects of this type before, we can help your team identify current and future-state business and technical requirements to consider in moving forward without the current software, while helping explore the industry’s current offerings and providing an unbiased perspective on the best tools for your organization.

Some items to start considering:

- Does it make sense to do a direct replacement of the existing system, or are there other departments within the company that could benefit from an investment in new software?

- What are the benefits and efficiencies of implementing new software while the current system is still functioning? This could include parallel reporting, giving the ability to reference the old while learning the new, and providing end users time to adjust without it being time critical.

- Customizability versus configurability of software: what makes the most sense for your company? What are the pros/cons?

- What budget do you have available? The perfect solution may be out there, but if budgetary constraints inhibit your options you may decide to plan for the expense early in the process.

- How urgent is the replacement? The answer to this question will help you gauge the feasibility of implementing different solutions and determine what to include in the initial project scope.

Choose a Path Forward

Once you have gathered all the potential options for replacement, it is time to decide. Depending on what the decision is, this step will look different for everyone. If you are replacing software, the next step is determining what software options exist and which is the best fit. If you are going a different route, such as building an in-house solution or using spreadsheets, you will want to get the appropriate resources organized to develop the plan to design and implement your new solution.

ALL4 can support your team through the software selection process. Our DSP team has extensive experience and industry knowledge, including subject matter experts (SME) across various states and HSE areas, and our team has implementation experience and partnerships with a variety of software vendors. ALL4 can:

- Provide vendor suggestions that can support identified business requirements and help set up appropriate vendor demos.

- Help ask vendor questions and offer professional guidance. We are familiar with the market and understand the areas of strength for various digital solutions.

- Assist in evaluating vendors against business and technical requirements, identifying potential gaps.

- Support developing a Request for Proposal (RFP) for vendors and/or implementation partners.

- Bring in a change management resource to support your team with a successful transition.

Get Contracts and Licensing in Order

If your replacement decision includes purchasing new software and/or including an implementation partner, it is time to get those contracts ironed out. Depending on who you are working with it can take time to come to licensing agreements and implementation contracts, and internal and legal reviews can add time to getting contracts signed. The sooner your project can get any contractual negotiations started and signed, the sooner the project can kick off.

Implement the Replacement

Whether you’re working with an implementation partner, vendor services team, or an internal team, now is the time to finalize the timeline, organize internal resources, and start progressing on the implementation process. Here are a few examples of what should happen in this phase:

- Develop an implementation timeline, start designing the new system (or process, forms, spreadsheets), and address necessary business and technical requirements during the design.

- Get the design approved by key decision makers and start configuration.

- If migrating data, figure out how data can be extracted from the old system and in what format, along with what kinds of data transformation may need to occur. If not migrating, decide where historical data will be stored and accessed in the future. Learn more about ALL4’s legacy data migration planning and approach here.

- Start building end user excitement and buy in and decide on how to roll out training. This is an area where a change management specialist can provide value.

- Train your system administrators and end users and go live!

- Once the new process is in place and confirmed to be working, finalize any data migration or archiving that needs to occur and retire the old system.

Set-up for Success

During the implementation, start having conversations on how your company will support the new software post go-live. To set up the new system for on-going success, you’ll want to have a long-term sustainment plan in place identifying who and how will the software be maintained and updated. Some options to consider:

- Does your internal team have the knowledge and resources to manage the software?

- Are you going to rely on the vendor when system changes are needed?

- Will you work with a consulting partner, like ALL4?

- Has the project been properly documented to ease knowledge transfers?

Following this roadmap can help your company move through the process of replacing an End-of-Life software solution. It is critical that you start looking into alternatives as soon as you can, so that you do not end up making rushed decisions or risk being out of compliance. A longer process greatly reduces the risk of causing stress to your team and end users and impacting the success of your project. If you would like to discuss further, please contact Kaitlin George at kgeorge@all4inc.com or 585-687-2124.

The SEC’s Final Rule on Climate Disclosures

On March 6th, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved the highly anticipated final rule for The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors. This rule will become effective 60 days after it is published in the Federal Register which is still pending. The rule amendment is aimed at compelling companies to disclose information about their climate-related risks to investors. However, the final rule significantly deviates from the proposal released two years ago, featuring weaker provisions that grant companies the authority to determine the extent of information to be shared. In a notable shift, the final rule mandates climate-related disclosures only if deemed “financially material.” Under the original proposal, all public companies would have been obligated to calculate and report both Scope 1 direct greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and Scope 2 indirect GHG emissions with no exceptions. In contrast, the final rule allows companies to report this information only if they consider it financially material. Approximately 40% of domestic public companies will be required to assess whether their emissions are material, exempting smaller companies and emerging growth businesses, generally those with less than $1.2 billion in annual revenues.

The final rule features several elements that significantly impact how companies approach climate-related disclosures in the United States (US). Below is a detailed breakdown of the final rule’s key takeaways:

- Companies registered as Accelerated Filers (AFs) and Large Accelerated Filers (LAFs) (non-exempt) are mandated and required to disclose their financially material Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions.

- Scope 3 GHG emissions are no longer required for mandatory disclosures.

- The first disclosures will be required in Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 for FY 2025 data and compliance will be phased in based on the registrant type.

- Companies will be required to seek limited assurance for their disclosures starting within 3 years of the final rule, moving to reasonable assurance for LAFs within 7 years. Limited assurance represents the foundational level of assurance, where the independent auditor gathers ‘sufficient and appropriate evidence,’ restricting assurance to particular aspects of the sustainability report.

- The final rule did not adopt double materiality (impact materiality and financial materiality); The final rule will rely solely on the traditional US legal definition of financially material which is defined as “a substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important in deciding how to vote or make other investment decisions”.

- Companies must disclose and be audited on the financially material impacts of severe weather events, carbon offsets, Renewable Energy Credits (RECs), and other climate-related factors where expenditures are greater than 1% of profits (before taxes including the disclosure of capitalized costs, expenditures, charges, and losses incurred.)

- Companies will be required to discuss identification, management, and oversight of climate-related risks, with the framework heavily based on Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) principles.

- Board oversight descriptions will be required with the disclosure of material climate-related targets and goals.

- The final rule includes the requirement that companies must disclose climate-related risk assessment and management processes.

- There will be mandatory electronic tagging of climate-related disclosures in Inline XBRL, a structured data language that allows filers to prepare a single document that is both human-readable and machine-readable.

As highlighted, the framework from the TCFD served as the foundation of the climate-related disclosure final rule. Given that the TCFD framework is also a key influencer in shaping other major climate standards, such as the European Union (EU) and International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards, it becomes a convenient starting point for companies seeking a streamlined approach to navigate through the new requirements.

Since its publication in March 2022, the SEC’s proposal received unprecedented attention, with over 24,000 comment letters, making it the most commented-on proposed rule in SEC history. While the final rule aims to establish a more formal and consistent public reporting system, dissenting SEC Commissioners, including Commissioner Caroline Crenshaw, argued during the live meeting that the information presented to investors will be incomplete. Crenshaw characterized the final rule as adopting an unnecessarily limited version of disclosures, describing it as a “bare minimum” step forward. She expressed concerns about passing the responsibility to future commissions to ensure investors receive necessary information, stating, “Today’s rule is better for investors than no rule at all, and that’s why it has my vote. But while it has my vote, it does not have my unencumbered support.”

The final rule mandates that all required disclosures, except for material Scope 1 and Scope 2 climate emissions, must be included in the annual 10K filing, with the latter being disclosed in the second-quarter 10Q filing. This schedule will allow companies additional time for annual emissions data collection. Under this framework, companies are entrusted to determine the materiality of their emissions without obligation to share their analysis with investors. While the final rule lacks a specific test to determine the financial materiality of emissions, experts anticipate that the inclusion of a materiality test will not result in a total lack of emissions reporting, as failure to disclose may expose companies to SEC fines or investor lawsuits if the information is later deemed material.

The SEC’s final rule sets compliance dates depending on registrant type and disclosure content. The rule mandates the disclosure of vital climate-related information in registration statements and annual reports, responding to the recognition that such risks significantly impact a company’s risk and financial performance. Acknowledging the costs and disclosure burdens, the final rule adopts a phased-in approach with exemptions for smaller companies. Initial compliance falls on the largest corporations or filers, mandating them to gather information from FY 2025 for reporting in FY 2026. This phased introduction also extends to assurance requirements. See the timeline below for a look at the SEC’s climate final rule phased-approach based off the SEC’s climate final rule fact sheet:

While hailed as a positive stride for sustainable development, critics argue that this final rule may be insufficient, lacking comprehensiveness. Nevertheless, it signifies progress in achieving consistent, comparable, and reliable climate-related information disclosure, attempting to meet the escalating demand for transparency on climate risks and management from investors. A notable drawback is the exclusion of Scope 3 GHG emissions, representing indirect emissions beyond a company’s control but within its value chain. John Tobin, a professor at Cornell University and former managing director of sustainability at Credit Suisse, emphasized the rule’s shortcoming in lacking requirements for disclosing certain Scope 3 emissions, particularly upstream supply chain emissions, which could pose significant risks to a company’s business. Critics argue that this misses the purpose of climate disclosures, which is to provide investors with information regarding a company’s exposure to climate-related risks, climate policy changes, energy prices, and shifts in consumer sentiments.

Despite criticisms, tying required disclosures to a materiality test may serve as a legal safeguard for the rule when it inevitably faces legal challenges. Many groups, including the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), have threatened to sue the Commission if it exceeds its legal authority. A total of 13 Republican-led states and two energy companies have already filed lawsuits against the new rule, just days after the final vote.

In addition to the SEC, there are currently several regulatory authorities that have adopted ESG reporting disclosures for the companies that operate and/or do business within their jurisdictions. With the addition of the SEC’s final rule, the following chart summarizes the current regions that have adopted ESG reporting as law.

Summary Chart of ESG Reporting Disclosure Requirements in Various Regions |

||

| Region | Reporting Requirements | Regulatory Authority |

| ASEAN | Mandatory and ‘comply or explain’ basis reporting for publicly listed companies in countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. | Detailed jurisdiction-specific requirements in GRI’s 2022 report. |

| Chile | Annual reports must disclose ESG information based on SASB and GRI, material climate-related risks (TCFD), and sector-specific SASB sustainability information. | Financial Markets Commission |

| China | Listed companies with high environmental impact must disclose various environmental information. | Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) |

| Egypt | ESG issues disclosure in annual reports for financial institutions (excluding banks) and listed companies. | Financial Regulatory Authority |

| European Union (EU) | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requires detailed reporting on ESG matters like climate change, environmental impact, social responsibility, human rights, and anti-corruption. | European Commission |

| Hong Kong | Mandatory and ‘comply or explain’ ESG reporting requirements for listed companies. | Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX) |

| India | Top 1,000 companies by market cap must disclose material business conduct and sustainability issues, including climate risks. |

Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) |

| New Zealand | Large publicly listed companies, insurers, banks, non-bank deposit takers, and investment managers must make climate-related disclosures. | Ministry for the Environment |

| United Kingdom (UK) | Mandatory climate-related risk disclosure for the largest listed businesses. | Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) |

| United States (SEC) | Climate final rule mandates climate-related disclosures if deemed “material,” impacting approximately 40% of domestic public companies. | Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) |

| United States (California) | Two state senate bills and one state assembly bill that collectively require certain public and private U.S. companies that perform certain business activities in California to provide disclosures about their GHG emissions

|

California Legislative |

The phase-in periods outlined in the SEC’s final rule should provide ample time for companies to adequately prepare for their reporting requirements. It’s worth noting that many of the more prescriptive and challenging elements proposed, such as Scope 3 GHG emissions and most financial statement requirements, are absent from the final rule. It’s crucial for companies to conduct a preliminary materiality determination to guide their disclosure and compliance preparation, including organizing their GHG emissions data and conducting a gap assessment to compare current voluntary disclosures with anticipated mandatory requirements. Additionally, companies should evaluate the need for additional governance, policies, controls, procedures, and digital software solutions to support reporting and data organization while also considering global climate disclosure requirements. Moreover, companies should develop a compliance plan based on their materiality determination, gap assessment, applicable phase-ins, and other climate disclosure requirements. The phased-in approach of the SEC’s final rule emphasizes the importance of providing investors with consistent, comparable, and reliable information, enabling companies to adjust based on their filing status. While the new rule represents progress towards comprehensive and standardized climate-related risk information, concerns remain about its effectiveness in meeting investor needs and addressing reporting gaps. The final rule reflects a delicate compromise between transparency demands and corporate autonomy.

ALL4 can provide support in materiality assessments, GHG accounting procedures, ESG reporting strategy, assurance services, setting carbon reduction targets, pursuing net-zero goals, and implementing climate initiatives. As companies navigate this evolving landscape, assistance from organizations like ALL4 becomes crucial in navigating materiality assessments, developing GHG accounting procedures, addressing ESG reporting strategy, and establishing assurance services, as well as setting carbon reduction targets and net-zero goals, and climate initiatives.

For inquiries, contact ALL4’s Sustainability experts at:

- Daryl Whitt, Technical Director of Climate Change & Sustainability, at dwhitt@all4inc.com

- James Giannantonio, Managing Consultant of ESG & Sustainability, at jgiannantonio@all4inc.com

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/sec-approves-rule-that-requires-some-companies-to-publicly-report-emissions-and-climate-risks

- https://www.sec.gov/news/statement/munter-statement-assessing-materiality-030922

- https://finance.yahoo.com/news/one-big-change-sec-climate-094602446.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAEorEcQy-YEvsfLQPI9hop4K_cAvDqPmD08e4b9G9NxC4NctpgFQQeOSqjo633Mk-92VtSRokrbLTNWb-YUJGI5n8I9o5KGtAgQo1GxQKUIUW3pkzJMnUtLLQ671skx_HIZyZJzlU2X0mKKTLbfy0DpBL-F4ihtRmUQI9ZA9z4Qu

- https://www.globalreporting.org/media/oujbt3ed/climate-reporting-in-asean-state-of-corporate-practices-2022.pdf

- https://www.investmentnews.com/regulation-and-legislation/news/sec-passes-climate-rule-that-leaves-no-one-happy-250403

- https://heatmap.news/economy/sec-climate-disclosure-change

- https://nam.org/manufacturers-sue-sec-on-proxy-rule-rescission-18335/

- https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/materiality#:~:text=Northway%2C%20426%20U.S.%20438%2C%20449,total%20mix’%20of%20information%20made

- https://www.sustain.life/blog/limited-assurance-vs-reasonable-assurance

Now Boarding: Mississippi Facilities to CAERS Version 5

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Combined Air Emissions Reporting System (CAERS) is officially being rolled out to 11 Mississippi pilot facilities in 2024!

U.S. EPA hosted a training in December 2023 with Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) to welcome Mississippi facilities to CAERS for reporting year (RY) 2023. The pilot Mississippi facilities that are required to report emissions for RY2023 will be expected to submit their reports using CAERS on or before July 1st.

Even if your facility isn’t required to report in CAERS this year, read on for some more information about what CAERS is!

What is CAERS?

CAERS is an online portal for facilities located within enrolled state, local, and tribal (SLT) programs to report air emissions annually or triennially in accordance with the Air Emissions Reporting Requirements (AERR) Rule. The portal is housed within U.S. EPA’s Central Data Exchange (CDX) platform and aims to decrease the amount of repeat data entry that is done by facilities. Currently, air emissions reported in CAERS can be imported in Section 5.2 of the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) and U.S. EPA hopes to link CAERS to other reporting platforms in the future, such as the electronic Greenhouse Gas Reporting Tool (e-GGRT), to further reduce repeated data entry by facilities.

I’m a facility located in Mississippi, what do I need to do to access CAERS?

A CAERS Subscriber Agreement must be completed by each facility that will report annual emissions within CAERS. The Subscriber Agreement (available here) must be signed by the responsible official who will be submitting and certifying the annual emissions report. Submission of the Subscriber Agreement also serves to register the responsible official as the Certifier in CAERS. Note that only one person is allowed to be listed as a Certifier for each facility. However, one person can be listed as a Certifier for multiple facilities. A few items to note about completing and submitting the Subscriber Agreement:

- The responsible official must already have an account in CDX prior to submitting the Subscriber Agreement.

- The signed Subscriber Agreement must be submitted as an attachment to a signed cover letter that is printed on the company’s letterhead.

- The signed cover letter and signed Subscriber Agreement can either be submitted as an original hard copy or as a scanned attachment via email. Both the mailing address and email address for submission are provided in the Subscriber Agreement.

- If you would like to authorize a person as the Certifier who is not the responsible official, you must also complete and submit MDEQ’s “Duly Authorized Representative (DAR) Designation Form (AIR Only)” that is available on MDEQ’s website.

If you are not the Certifier, you can request access to CAERS as a Preparer within CDX without going through the Subscriber Agreement process. Once you have logged in to your existing CDX account or created a new CDX account, you can add the “CAER: Combined Air Emissions Reporting” to your active program services list and follow the prompts to request access to your facility as a Preparer. Once all steps have been completed, you will be able to access the CAERS My Facilities page and request access to your facility in CAERS specifically. MDEQ will review the request in CAERS to ensure it matches the information submitted in CDX prior to granting the facility access request.

How do I complete my emissions report in CAERS?

Once Preparer and Certifier roles are established, you are now able to begin completing your emissions report in CAERS. CAERS offers multiple ways to develop your emissions report – data entry via the user interface, data entry via the bulk upload spreadsheet and file upload, or JSON file upload.

If your facility is brand new to CAERS, it is recommended that you start with the user interface option to establish your facility’s set-up. The CAERS user interface has built-in quality assurance (QA) checks that alert you immediately if something has been entered incorrectly. If you have submitted an AERR to MDEQ previously, some of the facility information will be pre-populated. Once your facility is set-up correctly in CAERS, you can then download the bulk upload spreadsheet template, which will now be filled in with your facility-specific information and complete your emissions data entry using the spreadsheet.

Once you are done with your report in CAERS, you will be required to run a QA check of your report and address any errors prior to submission. Pro-tip: you can complete these QA checks at any point during report development to check for errors as you go! Once your report passes the QA check, you are then able to notify the Certifier within CAERS that the report is ready for their review/submission or submit the report directly if you have Certifier access.

ALL4 has been assisting facilities with reporting through CAERS since its creation and will be helping other Mississippi facilities navigate reporting in CAERS for the first time. Although only the pilot facilities will be required to report in CAERS this year, you can be taking steps now to get ready for CAERS in the future. If you have any questions about setting up your account in CAERS or developing your emissions report in CAERS, please reach out to Stacy Arner-Jenkins at sarner@all4inc.com!

Lime Manufacturing NESHAP Supplemental Proposal Issued

A supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking to the 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart AAAAA (National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants for Lime Manufacturing Plants [Lime Manufacturing NESHAP]) was published in the February 9, 2024 Federal Register. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) is proposing to revise the proposed hydrogen chloride (HCl), mercury, organic hazardous air pollutant (HAP), and dioxin/furans (D/F) emissions limits. Comments on this supplemental proposal are due March 11, 2024.

Background

To supplement the U.S. EPA’s 2020 residual risk and technology review (RTR) and as a result of a D.C. Circuit Court decision, the U.S. EPA proposed maximum achievable control technology (MACT) standards for the following previously unregulated HAPs on January 5, 2023: HCl as a surrogate for acid gas HAPs, mercury, total hydrocarbon (THC) as a surrogate for organic HAP, and D/F. This supplemental proposal addresses concerns related to economic impacts of the 2023 proposal on small businesses and data quality issues identified during the comment period.

Updates to Proposed Emission Standards

HCl – Dolomitic lime (DL) and dead burned dolomitic lime (DB) subcategories were added for vertical kilns and the proposed numerical limits for several subcategories were updated (see Tables 2 and 3 of the preamble to compare both sets of limits). Corrections were made to the kiln type subcategorization used in the calculations to establish the proposed limits.

The Clean Air Act (CAA) allows the U.S. EPA to consider a health-based emission limit (HBEL) for a HAP with an established health threshold. A D.C. Circuit Court decision related to the Brick NESHAP found that the U.S. EPA had not sufficiently supported its determination that HCl has an established health threshold. Scientific evidence and discussion on whether or not HCl has a health threshold is provided in the preamble and docket for this rulemaking. Thus, U.S. EPA is proposing an HBEL for HCl of 300 tons per year (tpy), with short-term emissions not to exceed 685 pounds per hour (lb/hr). The U.S. EPA is requesting comment on an appropriate structure for incorporating the HBEL for HCL in the rule text. This is the first time in any recent rulemaking that U.S. EPA has proposed to incorporate an HBEL and will be of interest to other industries where NESHAP are being revised to fill regulatory gaps.

Mercury – As part of the January 5, 2023 proposed rulemaking, the U.S. EPA evaluated the use of an intra-quarry variability (IQV) factor to account for the naturally occurring variability of mercury content of the raw materials. The U.S. EPA concluded that they did not have sufficient data to apply an IQV factor at that time. The lime industry provided clarification and additional information concerning storage pile homogenization and quarry sampling during the comment period, and the U.S. EPA has applied an IQV factor in this update. The originally proposed mercury emission limit for new and existing quick lime (QL) and DL sources increased from 24.9 pounds per million tons of lime produced (lb/MMton) for both new and existing sources to 27 lb/MMton for new sources, and 34 lb/MMton for existing sources in the QL subcategory (see Tables 2 and 4 of the preamble to compare all mercury limit changes).

Subcategories were removed for new and existing sources because the U.S. EPA determined there were minimal differences in emissions across kiln types and that residence time has little impact on mercury emissions.

THC as a surrogate for organic HAP – The U.S. EPA is proposing to change the format of the standard for organic HAP emissions from THC as a surrogate to an aggregated emission standard comprised of the eight organic HAP consistently identified in the data analysis (formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, toluene, benzene, xylenes [m, o, and p isomers], styrene, ethylbenzene, and naphthalene). The proposed emission limit is equivalent to the sum of three times the representative detection level (3xRDL) of the test method for each of the eight organic HAPs (1.7 ppmvd at 7 percent oxygen versus the originally proposed THC limit of 0.86 ppmvd as propane at 7 percent oxygen).

D/F – The U.S. EPA is proposing to update the proposed D/F numerical limits for new and existing sources based on a change to the sample collection volume used in the 3xRDL calculations. This change results in a slightly higher emissions limit (0.037 ng/dscm (TEQ) at 7 percent oxygen versus the originally proposed 0.028 ng/dscm (TEQ) at 7 percent oxygen). As with the original proposal, the limits for new and existing sources are the same. The U.S. EPA is requesting any additional D/F stack test data comprised of at least three test runs to supplement its data set.

Other Proposed Changes

- Definitions of new and existing source will be based on the January 5, 2023, proposal date.

- Existing sources will have three years from the effective date of the final amendments to comply with the new emissions limits, subject to certain exemptions.

- The U.S. EPA is proposing a definition of “stone produced” used in the units of measure for the HCl and Hg emissions limits to indicate it refers to the production of lime.

- The U.S. EPA is proposing to add emissions averaging which provides compliance demonstration flexibility. The emissions averaging alternative is for HCl and mercury emissions across existing kilns in the same subcategory located at the same facility. A 10 percent adjustment factor will be incorporated into the emissions averaging approach lowering the proposed averaging limit (e.g., alternative mercury averaging 31 lb/MMton stone produced versus 34 lb/MMton stone produced with no averaging).

Implications of the Proposal

There are 34 major sources subject to the Lime Manufacturing NESHAP. The final rule will include first-time emissions limits for these facilities, which will come with new requirements for emissions testing, monitoring, reporting, and (in some cases) additional controls. While the re-proposal lessens the potential burden at a facility somewhat, the U.S. EPA estimates the average annual cost per facility to comply with these new requirements will be more than $5 million. The U.S. EPA is seeking comments on all aspects of the proposal, particularly the proposed HBEL for HCl, and is requesting additional D/F stack test data.

If your facility is impacted by this rule, ALL4 can help you develop comments, collect and submit data, develop a compliance strategy, design a stack testing program, and improve your monitoring and data collection systems. Please reach out to your ALL4 Project Manager or JP Kleinle for more information on how we can help. We’ll be tracking the final rule requirements, which are due to be signed on June 30, 2024.

Revisions to the Risk Management Program Safer Communities by Chemical Accident Prevention Requirements

Introduction

On February 27, 2024, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) signed final Safer Communities by Chemical Accident Prevention (SCCAP) Risk Management Program (RMP) regulations. The amendments include changes and enhancements to accident prevention program requirements, emergency preparedness requirements, and increased public availability of chemical hazard information for facilities subject to the “Chemical Accident Prevention Provisions,” codified at 40 CFR Part 68.

Background

The 1990 Clean Air Act (CAA) Amendments include Section 112(r), the accidental release prevention rule, to “provide for the prevention and mitigation of accidental chemical releases.”1 The U.S. EPA published the initial RMP regulation in 1996 with risk management requirements for covered sources. The rule requires owners and operators of stationary sources that produce, process, handle, or store regulated hazardous substances in amounts above threshold quantities, as promulgated under Section 112(r), to develop and implement an RMP. An RMP includes development of a hazard assessment, an accident prevention program, and an emergency response program. An RMP must be established prior to any regulated substances being present on-site above threshold quantities at a facility. Once an RMP is established and a risk management plan is submitted to the U.S. EPA, it is subject to review and renewal every five years, and includes documentation of a five-year accident history at the facility. The purpose of the RMP regulations is to require facilities to:

- Identify the potential effects of an accidental release of a regulated substance,

- Identify the proactive actions established to prevent an accident, and

- Establish emergency response procedures in the event an accident occurs.

Development of an RMP includes consideration of the program level specific to each process at the facility. There are three program levels under the RMP rule, with Program 1 applying to “extremely safe facilities,” Program 2 applying to facilities subject to threshold quantities that trigger Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) or U.S. EPA planning requirements, and Program 3 applying to facilities that do not meet Program 1 requirements, but are subject to OSHA Process Safety Management (PSM) requirements. RMP requirements are specific to the applicable program level, but generally include:

- Conducting a hazard assessment,

- Developing a prevention program,

- Establishing an environmental emergency-response program, and

- Operating an overall management system.

Threshold quantities vary by the specific regulated substance, between 500 and 20,000 pounds onsite for toxic chemicals and 10,000 pounds onsite for flammable substances. U.S. EPA estimates approximately 11,740 facilities have filed current RMPs and are potentially affected by the amended RMP regulations.

Amendments to the Risk Management Program Regulations

Amendments to the RMP rule were published in January 2017 and contained new provisions addressing prevention program elements, such as a Safer Technology and Alternatives Analysis (STAA), incident investigation root cause analysis (RCA), emergency response coordination with local responders, and availability of information to the public. Most of the amendments, however, were rescinded in December 2019. In August 2022, EPA proposed amendments to the RMP regulations aimed at restoring many of the requirements in the 2017 rule in response to Executive Order (EO) 13990, “Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis” 2 directing Federal agencies to review existing regulations and take action to address Administration priorities, including improving resilience to climate change impacts and environmental justice (EJ).

The 2024 amendments to the RMP rule implement changes the U.S. EPA considers as better focused prevention programs compared to the 2017 amendments and promotes better information availability, employee participation, and emergency response compared to the 2019 reconsideration. U.S. EPA believes many, if not most, regulated sources will respond by implementing enhanced prevention measures to avoid accidents, but increased public and employee participation will help prevent sources from evading accident-prevention requirements. U.S. EPA believes the “prevention-focused” nature of these revisions could provide additional protection to human health and the environment. Amendments included in the 2024 RMP rule include:

- Hazard Evaluation Amplifications – Program 2 and 3 regulated processes, which already were required to conduct hazard reviews of regulated substance processes, must now address:

- Natural hazards (defined as meteorological, environmental, or geographical phenomena that have the potential for negative impact, and accounting for impacts due to climate change).

- Loss of power, including, for covered processes, a requirement for monitoring equipment to have standby or backup power.

- Stationary source siting, including the placement of processes, equipment, buildings, and their potential hazards posed to the public.

- Prevention Program Provisions – Several modifications intended to enhance community safety are included in the 2024 RMP rule, including:

- Program 3 regulated processes in either the petroleum and coal products industries (NAICS code 324) or chemical manufacturing industry (NAICS code 325) must consider the practicability of applying safter technologies and alternatives, which includes inherently safer technologies or design (IST/ISD). Additionally, facilities in NAICS code 324 using hydrofluoric acid (HF) in an alkylation unit must consider safer alternatives to HF alkylation.

- For Program 3 regulated processes, the implementation of at least one passive risk reduction measure, or an IST/ISD or a combination of active and procedural measures that would be equal to, or greater than, the risk reduction from a passive method.

- A root cause analysis must be performed and completed within 12 months for Program 2 and 3 processes following an RMP-reportable accidental release.

- A third-party compliance audit must be performed, no later than three years after the previous compliance audit, following an RMP-reportable accidental release.

- Employees knowledgeable in a Program 3 process must be included in the implementation of Process Hazard Assessments (PHAs), incident investigations, and compliance audits, and be given authority to recommend to the operator in charge that a process be partially or completely shut down based on the potential for a catastrophic release.

- Emergency Response – RMP facilities should partner with community emergency response agencies to ensure a community notification system is established for reporting accidental chemical releases, and coordinate with local officials to establish an appropriate frequency, at a minimum of once every ten years, for conducting a simulated accidental release field exercise.

- Information Availability – RMP facilities must provide specific chemical hazard and emergency preparedness information within 45 days of receiving a request from the public living, working, or spending significant time within six miles of the facility fenceline.

- Clarifications to Regulatory Definitions – Updates to process safety information, hot work permit documentation (hot work permits must be retained for three years), and Recognized and Generally Accepted Good Engineering Practices (RAGAGEP) compliance requirements.

Potential Impacts to Regulated Facilities

Facilities regulated under CAA Section 112(r) will be required to comply with modifications to the chemical accident prevention regulations within timeframes established by the 2024 RMP rule. STAA, root cause analysis, employee participation, and information availability requirements must be met within three years for impacted facilities. A revised emergency response field exercise must be performed by March 15, 2027, or within ten years from a previous exercise conducted between March 15, 2017 and August 31, 2022. A revised risk management plan must be submitted within four years.

How Can ALL4 Assist?

ALL4 has a staff of experienced Environmental and Safety Consultants familiar with RMP and PSM regulations, hazard assessments, prevention programs, and emergency response planning. We are able to provide facilities with evaluations and recommendations to stay current and compliant with revised CAA Section 112(r) requirements. ALL4 can evaluate your facility’s RMP status, help you develop a timeline for implementing and complying with the new requirements, and work with you to address your compliance needs. Contact Ryan Cleary at rcleary@all4inc.com or (919-230-0716) for more information.

1Accidental Release Prevention Requirements; Risk Management Programs Under Clean Air Act Section 112(r)(7); Amendments, 64 Fed. Reg. 964 (January 6, 1999).

2The White House; Executive Order on Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-protecting-public-health-and-environment-and-restoring-science-to-tackle-climate-crisis/ (January 20, 2021).