Electric Generating Units: Are You Submitting the Appropriate Electronic Reports for NSPS TTTT?

40 CFR Part 60, Subpart TTTT, Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Electric Generating Units (NSPS TTTT) establishes emissions standards for new stationary combustion turbines for the control of greenhouse gases (GHGs). NSPS TTTT applies to certain steam generating units, integrated gasification combined cycle units (IGCCs), and stationary combustion turbines [i.e., electric generating units (EGUs)]. For NSPS TTTT to apply, these units must (1) have a base load rating greater than 250 million British Thermal Units per hour (MMBtu/hr) of fossil fuel and serve generators capable of selling greater than 25 megawatts (MW) of electricity, and (2) commence construction after January 8, 2014 or commence modification or reconstruction after June 18, 2014.

Certain emissions limits for units subject to NSPS TTTT require electronic self-reporting through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (U.S. EPA’s) Emissions Collection and Monitoring Plan System (ECMPS) Client Tool, which is managed by U.S. EPA’s Clean Air Markets Division (CAMD). Specifically, for units that are required to demonstrate compliance with emissions limits on a 12-operating-month rolling average basis, quarterly reports are required. For new applicable units that have recently commenced operation, the first report must be submitted after accumulating 12 operating months of data, for the first calendar quarter that includes the 12th operating month. We’ve learned that there is confusion on initiating NSPS TTTT-specific reports within ECMPS, especially for those facilities already reporting under the Acid Rain Program, or other regulations that require reporting.

Possible Compliance Gaps

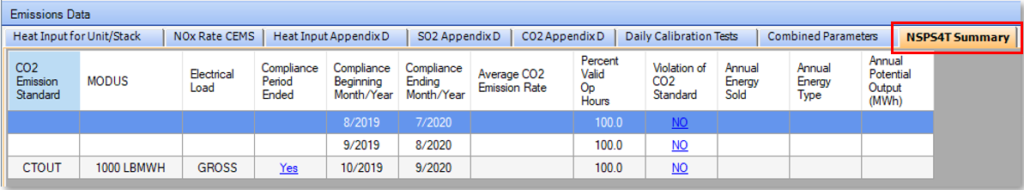

Affected sources, with applicable 12-operating-month rolling average CO2 emissions standards are required to submit reports electronically. For example, an affected source that is subject to an output-based emissions limit (e.g., lb CO2/MW) and has gathered more than 12-operating months of data should have an NSPS4T Summary tab in their ECMPS Client Tool, highlighted in the figure below.

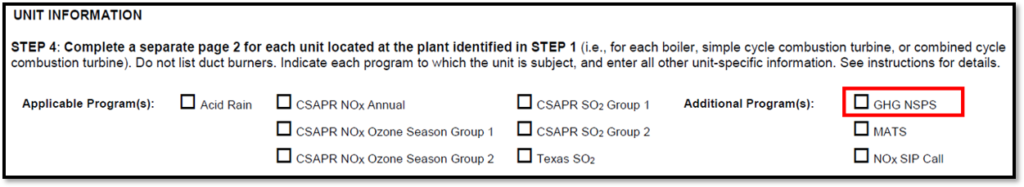

However, for NSPS TTTT data to be submitted via ECMPS, a Certificate of Representation Form must be properly completed and sent to CAMD, and older versions of the Certificate of Representation Form did not identify GHG NSPS (including NSPS TTTT) as being an applicable program. Therefore, while many Facilities may be subject to NSPS TTTT, they may not have submitted a Certificate of Representation Form that indicates NSPS TTTT applies, as presented in the image below.

Required Action Needed

For many combined-cycle combustion turbine and other EGU projects that were permitted in the early to mid-2010s, NSPS TTTT (originally proposed on June 2, 2014, and finalized on October 23, 2015) was a new rule, with little compliance guidance published. Moreover, electronic report submissions were not due until 12-operating months of data were collected, further prolonging required reporting.

CAMD does not maintain a list of units subject to electronic reporting under NSPS TTTT; therefore, the responsibility falls to owners and operators to inform CAMD of a unit’s correct applicability via the Certificate of Representation Form. Whether your newly constructed EGUs are coming online or have been operating for more than a year, it is important to review your NSPS TTTT reporting obligations.

Because these reporting platforms and obligations can, at times, be a little unclear, our ALL4 team has formed relationships within U.S. EPA’s CAMD over the years and has assisted our clients with navigating ECMPS and electronic quarterly reporting. We’re always ready to assist you with compliance questions, so if this article made you stop and think about your NSPS TTTT reporting obligations or if you have additional questions, do not hesitate to reach out to Frank Dougherty at fdougherty@all4inc.com or 281-937-7553 x302.

Final Amendments to 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart MM Signed October 9, 2020

On October 9, 2020, U.S. EPA finalized amendments to 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart MM (National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants for Chemical Recovery Combustion Sources at Kraft, Soda, Sulfite, and Stand-Alone Semichemical Pulp Mills)i. This action was highly anticipated, as mills were under a deadline to conduct a performance test by October 13, 2020, and some of the amendments pertained to how certain operating parameter limits were to be established during the test (i.e., for fan amperage). While most mills tested in advance of the amendments being finalized, the final rule provides some certainty going forward. Some background on the rulemaking and additional details about the final amendments are provided below.

BACKGROUND

40 CFR Part 63, Subpart MM regulates recovery furnaces, smelt dissolving tanks, lime kilns, and other combustion units at pulp mills. In particular, the rule establishes emissions limits for hazardous air pollutant (HAP) metals for existing sources [as particulate matter (PM)] and gaseous organic HAP for certain new sources [as methanol or total hydrocarbons (THC) depending on the type of source]. The initial compliance date was March 13, 2004. Amendments to Subpart MM were proposed on December 30, 2016 as part of U.S. EPA’s 8-year Residual Risk and Technology Review (RTR), and were finalized on October 11, 2017 with a compliance date of October 11, 2019, except that a performance test was due by October 13, 2020. Other significant changes to the rule included reduced allowances for opacity exceedances, new emissions quantification requirements, provisions for maintaining proper operation of the Automatic Voltage Control (AVC) for electrostatic precipitators (ESPs), removal of exemptions during periods of startup, shutdown, and malfunction (SSM), and electronic reporting requirements. Additional information about the 2017 amendments can be found here.

Amendments to the 2017 final rule were proposed on October 31, 2019 to correct cross reference errors, including to clarify that a numerical operating limit for AVC is not required, and to add the method for establishing the minimum scrubbing liquid flowrate for smelt dissolving tank scrubbers, which was accidentally omitted from the 2017 final rule. However, the most significant updates pertain to the alternative fan amperage operating parameter for certain smelt dissolving tank scrubbers that was included in the 2017 final rule.

SCRUBBER FAN AMPERAGE

The 2017 final rule incorporated an alternative parametric monitoring compliance method for certain smelt dissolving tank scrubbers (i.e., “dynamic scrubbers that operate at ambient pressure” and “low-energy entrainment scrubbers where the fan speed does not vary”). Instead of pressure drop, which was determined not to be an appropriate indicator of compliance for these types of scrubbers, the rule included fan amperage as an alternative parameter. Many mills already utilized fan amperage for these scrubbers as a result of site-specific alternative monitoring petitions for compliance with the original rule.

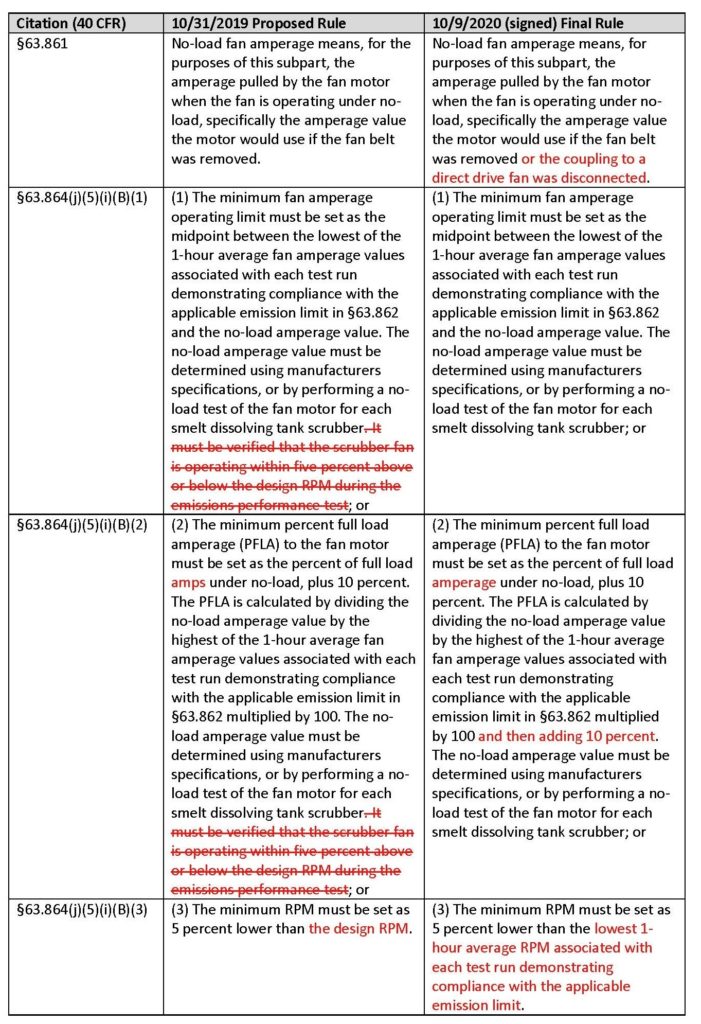

However, as mills began to prepare for the first periodic performance test, it was determined that the method for establishing the numerical fan amperage minimum operating limit was problematic. The 2017 final rule stated that the minimum fan amperage operating limit was to be set equal to the lowest 1-hour average value achieved during the performance test. Due to the natural variability of fan amperage for these scrubbers while operating properly, it was determined that these new operating limits would be difficult to meet on a continuous basis, and that lower fan amperage values would not necessarily represent excess emissions. U.S. EPA agreed with this determination and included three new alternatives to pressure drop for these scrubbers in the 2019 proposed amendments, pertaining to fan amperage, percent full load amperage (PFLA), and revolutions per minute (RPM) of the scrubber fan motor.

However, all three options included a requirement to keep the RPM of the scrubber fan motor within 5% of the design value. That was determined to be another problematic provision, as the design value may not be available due to the age of the unit, the motor may have been changed since the original installation of the scrubber, and measuring RPM during the test would be difficult, impossible, or dangerous. It was also noted that it should not matter whether the RPM of the scrubber motor is within 5% of the design value if the performance test demonstrates compliance with the applicable emissions limit. In the 2020 final rule, the requirement to operate the scrubber fan motor within 5% of its design RPM was removed from all three options. The definition of no-load fan amperage was also updated. A comparison of the 2019 proposed provisions relating to these three options and the 2020 final provisions is provided below (red text indicates a change from the 2019 proposal):

CLOSING THOUGHTS

On April 21, 2020, Subpart MM was remanded (without vacatur) back to U.S. EPA due to an unrelated court case concluding that the rule does not regulate all HAPs that are known to be emitted from the sources affected by the rule. This concept is referred to as “HAP gap,” and Subpart MM is not the only rule that will be impacted by this determination. So, while there is now clarity for affected sources regarding the 2019 proposed amendments, mills can expect to see more activity for this rule in the coming months and years. For now, mills should review the final rule, especially if using the fan amperage alternative compliance parameter, and continue with ongoing compliance obligations.

ALL4 will keep you posted on further updates to the rule, but should you have any questions or want to discuss in more detail, please contact your Project Manager or Lindsey Kroos.

iThis action also finalized amendments to 40 CFR Part 60, Subpart BBa (Standards of Performance for Kraft Pulp Mill Affected Sources for Which Construction, Reconstruction, or Modification Commenced After May 23, 2013); however, this article focuses solely on 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart MM.

New York’s Air Toxics Program: Part 212, What you need to know

The goal of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s (NYSDEC’s) air program is to protect the public and the environment from the adverse effects of exposure to air contaminants. As part of this protection, Title 6 Part 212 of New York Codes, Rules, and Regulations (NYCRR) includes regulations applicable to process operations at stationary sources of emissions. The Part 212 regulations achieve public and environmental protection via assessments of emissions control technologies and through an assessment of site-specific emissions and resulting ambient air concentration levels. There are three groups of air contaminants for process sources that include pollutants with a National Ambient Air Quality Standard (i.e., NAAQS or criteria pollutant), High Toxicity Air Contaminant (HTAC), and other non-criteria/HTAC air contaminants The program codified in Title 6 Part 212 of New York Codes, Rules, and Regulations (NYCRR) requires an analysis to determine how much control is needed to reduce air emissions to concentration levels such that human health is not adversely impacted. Although the Part 212 regulations have been in place for some time, NYSDEC has become more diligent in making sure facilities are addressing it with permit modifications and renewals.

Part 212 regulates air pollutant and air contaminant emissions from emissions sources associated with any process operations at facilities in the state of New York. For the purposes of the rule, the definition of process operation is:

“Any industrial, institutional, commercial, agricultural or other activity, operation, manufacture or treatment in which chemical, biological and/or physical properties of the material or materials are changed, or in which the material(s) is conveyed or stored without changing the material(s) if the conveyance or storage system is equipped with a vent(s) and is non-mobile, and that emits air contaminants to the outdoor atmosphere. A process operation does not include an open fire, operation of a combustion installation, or incineration of refuse other than by-products or wastes from a process operation(s).”

To assist regulated facilities with understanding Part 212 regulations, the Division of Air Resources developed DAR -1, which provides guidance on how to comply with the requirements of the Part 212 regulations. DAR-1 outlines the control requirements for the emissions of each air contaminant based on an assigned Environmental Rating and provides guidance for implementing the regulation.

Part 212 applies to all facilities with process operations, whether they have Title V permits, State Facility permits, or have Minor Facility Registrations:

(1) upon issuance of a new or modified permit or registration for a facility containing process emission sources and/or emission points;

(2) upon issuance of a renewal for an existing permit or registration.

Some process operations are exempted from the rule as described in Subpart 212.4 as they are regulated by other rules that take precedence. Additionally, 40 CFR Part 60 New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) and 40 CFR Part 61 and 63 National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) sources may be considered in compliance with Part 212 under certain conditions as described in the Part 212 regulation for those pollutants covered under those rules.

Facilities that are regulated under Part 212 must evaluate the amount of their air contaminant emissions, including criteria, HTAC, and non-criteria/non-HTAC compounds. For those contaminants on the HTAC list, the emissions rate in pound per year (lb/year) is compared to the threshold given in Part 212 Subpart 2.2 Table 2 to determine if the regulations apply. For those air toxics emitted as part of the process operation but not listed in the HTAC table, a threshold of 100 lb/year is used for assessing regulatory applicability.

For those air contaminants for which the emission thresholds are exceeded, the following steps are required to demonstrate compliance:

- Perform an air modeling screening analysis for the air contaminant using U.S. EPA’s AERSCREEN air dispersion model.

- Should the screening analysis not demonstrate compliance, perform refined air dispersion modeling using U.S. EPA’s AERMOD air dispersion model. When refined modeling is required, an air modeling protocol proposing the methodology to be used in the AERMOD demonstration must be submitted to NYSDEC and approved before the modeling can be executed.

- If compliance with Part 212 cannot be demonstrated with air dispersion modeling at the current emissions rates, a more stringent permit limit must be taken to bring concentrations below the applicable Short-term and Annual Guideline Concentrations (SGC/AGC) or the installation of additional controls may be required.

Facilities that are performing a Part 212 analysis during a permit renewal process are also often required to perform 1-hour nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and 24-hour and annual particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5) demonstrations if the facility has not been required to do one since those NAAQS were promulgated, in 2010 and 2012, respectively.

How can ALL4 help?

ALL4 air quality experts are actively involved in helping facilities in New York demonstrate compliance with Part 212. Determining the applicability of the regulation, characterizing the sources and emissions that are affected, and completing the required air dispersion modeling demonstration can be a challenge, especially given the low thresholds of many of the HTACs. If your facility’s permit or registration is nearing time to renew, or you are planning a project that requires a permit modification, ALL4 can help:

- Determine whether your facility has a process operation that is subject to Part 212.

- Quantify your toxics emissions and sources to determine which need to be evaluated to show compliance with the rule.

- Perform an AERSCREEN modeling analysis to assess compliance for each applicable toxic.

- For those toxics for which the AERSCREEN analysis is unsuccessful, perform refined modeling using the AERMOD dispersion model to show compliance.

- Work with you to determine control requirements or other ways to reduce emissions to bring the facility into compliance should modeling show concentrations above the thresholds.

- Perform NO2 and/or PM5 modeling if NSYDEC has also asked for those analyses.

In ALL4’s experience, AERSCREEN often overstates concentration levels because of the screening meteorology it uses that is designed to replicate worst case dispersion conditions. As a result, we find that in most cases facilities that have to demonstrate compliance with Part 212 air dispersion modeling will need to go to AERMOD. Typically, we would suggest skipping the AERSCREEN analysis and straight to AERMOD refined modeling. However, since DAR-1 requires an air modeling protocol be submitted to NYSDEC before AERMOD can be used to satisfy the Part 212 requirements, which requires additional time and effort to gain approval, and because in the course of setting up the AERMOD analysis most of the information required for AERSCREEN is generated as part of that process, we recommend trying AERSCREEN first to confirm that a refined air dispersion modeling analysis is required..

If you’d like to discuss whether your facility is subject to Part 212 as part of an upcoming renewal or modification, feel free to contact your ALL4 Project Manager or Rich Hamel. We’d be happy to share what we’ve learned in our experiences with this regulation and assist you in any way we can.

Have You Ever Wondered About U.S. EPA’s Regulatory Process?

Have you ever wondered about the process behind U.S. EPA’s rule development? Decoding a final rulemaking in Federal Register amendatory language can seem to take forever, but the road to arrive at that final rule can be months, years, or even decades long. Regardless of how long it takes to finalize a rule, the basic steps are generally the same. This article aims to familiarize readers with the federal regulatory process.

Regulatory Drivers

There are several reasons U.S. EPA develops a rule. One of the major drivers are laws enacted by Congress. Read any of the risk and technology review (RTR) rules promulgated by U.S. EPA this year and you’ll see references to Section 112 of the Clean Air Act (CAA) and U.S. EPA’s summary of the statutory language requiring the Agency to conduct the rulemaking.

But laws aren’t the only reason U.S. EPA embarks on a rulemaking: court decisions also drive regulation, or in many cases, revisions to regulations. For example, in July of this year, U.S. EPA proposed amendments to the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) for Major Sources: Industrial, Commercial, and Institutional Boilers and Process Heaters, otherwise known as Boiler MACT. The proposal was in response to a court decision that found U.S. EPA had erred in setting certain numerical emission limits.

There are also other rulemaking drivers such as petitions for rulemaking, technical corrections, and Executive Orders. If you’re interested in the drivers behind a particular rule, U.S. EPA summarizes the reasons and their statutory authority for any rulemaking in the preamble that accompanies the regulatory language.

Proposed Rulemaking

After initiating the rulemaking, U.S. EPA develops and publishes a proposed rule. To develop the proposal, the Agency gathers information from a variety of sources. U.S. EPA sometimes meets with industry stakeholders, environmental advocacy groups, and state and local regulators. The Agency can consult their environmental databases such as the National Emissions Inventory (NEI), control technology databases (e.g., the RACT/BACT/LAER Clearinghouse or “RBLC” database), and the Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) database. U.S. EPA may also issue an information collection request (ICR) to facilities potentially subject to the rulemaking to collect information on processes, practices, controls, emissions, and other items. After collecting the necessary data, U.S. EPA analyzes the information to develop emission limits, work practices, monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements with statutory requirements, legal precedents, Agency policy, and the overall objectives of the rulemaking in mind.

Several offices within U.S. EPA are involved with development, either directly or through internal review. These include the Office of General Counsel (OGC), the Office of Policy (OP), the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA), and the Office of Research and Development (ORD). U.S. EPA also analyzes the environmental and economic impacts of the rule and conducts various reviews required by Executive Orders such as Executive Order 12898: Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. This process can take months or years to complete.

But before U.S. EPA can publish a proposed rule, the Agency must determine if the rulemaking will be “significant” under Executive Order 12866. Significant rulemakings are those that meet certain criteria in terms of the impact the regulatory action might have. For example, rules that have annual cost of $100 million or more are classified as significant, as well as those rules that might interfere with actions by other agencies. If the rulemaking would be significant, it must undergo interagency review by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Once all necessary reviews are complete, the U.S. EPA Administrator signs the proposal, the rule is published in the Federal Register, and the docket is opened so the public can view the information that was used to develop the rule and how the impacts were estimated.

Public Input and Finalization

After publication of the proposal in the Federal Register, U.S. EPA accepts comments on the rule, usually for a period of 30 to 90 days. U.S. EPA might also hold public hearings to allow members of the public, the regulated community, and other stakeholders, an opportunity to voice concerns with the proposal. Often, U.S. EPA indicates in the preamble to the proposed rule the items or questions for which it is most interested in receiving comments or additional information. Following the close of the public comment period, U.S. EPA will review and consider comments and data submitted to the Agency and develop the final rule. The final rule must undergo OMB review if it is deemed significant, just like the proposed rule. The final rule is published in the Federal Register following signature by the Administrator, many times at least a year after the proposed rule was published. Some regulations are effective immediately and some have a delayed effective date.

When Final Doesn’t Mean Final

U.S. EPA’s initial publication of a final rule is often not the end of the road. Section 307 of the CAA allows for judicial review of issues raised “with reasonable specificity during the period for public comment.” Additionally, if parties have objections that were impracticable to raise during the comment period, or if parties have objections central to the outcome of the rule for which the basis came about after the comment period, U.S. EPA can reconsider those issues, and sometimes the effective date of a rule is stayed while reconsideration proceeds. But, if the Agency refuses to reconsider their final action, petitioners can turn to the courts.

Court decisions can have major impacts on not only the rule in question, but on future rules developed by the Agency. For example, a court decision made in 2008 regarding the legality of startup, shutdown, and malfunction exemptions has prompted U.S. EPA to remove these exemptions in the recent RTR rules. Court decisions have also shaped the way U.S. EPA calculates numerical emission limits under Sections 112 and 129 of the CAA. But while litigation can sometimes result in more favorable outcomes, the often-lengthy process adds another level of uncertainty for the regulated community. For example, U.S. EPA has been trying to establish final Boiler MACT standards for about 20 years now.

How to Stay Informed

The good news is that there are opportunities to help shape the regulations that affect your industry. Check out U.S. EPA’s website on how to be involved in the regulatory process. Sign up for email alerts from Regulations.gov or federalregister.gov. Join and participate in your industry’s trade associations. Attend environmental and trade association conferences. Reach out to your consultants! ALL4 is involved with several industry trade associations and we routinely monitor both the federal and state-level regulatory pipelines to keep ahead of new and revised rules. Contact your ALL4 project manager or Philip Crawford with questions about how to get involved or upcoming rules affecting your industry.

Meet John Hinckley

John Hinckley // Senior Project Manager // Vermont Regional Support

How does it feel being ‘The New Kid on the Block’?

Well, it didn’t take long to not be known as ‘The New Kid’ with our recent additions to the team! Onboarding has been great, and I’ve been able to hit the ground running with a lot of excitement and energy around expanding ALL4’s brand in the New England market. On the technical side, I dove right in working with ALL4’s clients in Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, Maine, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Georgia, so it feels good to be contributing.

What has surprised you the most about working at ALL4?

There is a vast amount of knowledge and experience amongst my team members. As a new(er) employee, I have valued the “one for all, all for one” collaborative approach on projects. It has been awe-inspiring to work alongside ALL4’s staff, who I get to learn from and vice versa.

What technical and regulatory drivers have your attention right now?

Two come to mind, and there is one that I’m keeping tabs on:

- Changes to New Hampshire’s air toxics rule (Env-A 1400) could trigger a number of permitting activities and possibly operational and mechanical changes at facilities to comply with newer, more stringent requirements.

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) proposed to revise the particulate matter (PM) emissions limits in Title 6, Part 227-1 of the New York Codes, Rules and Regulations (6 NYCRR 227-1) for stationary combustion installations. I recently wrote a blog describing the revisions that will likely reduce air emissions of particulate matter on the one hand, and which may trigger additional emissions control expenditures on the other hand.

- Vermont has not formally proposed any changes to its air pollution control regulations in 2020; however, I’m still keeping tabs on this.

What’s in store for 4Q2020 and as you look ahead to 2021?

I will be focusing on connecting in-person and virtually with existing/new clients, business partners, and colleagues to make a strong finish to 2020 and to gear up for 2021. Look for an upcoming blog from me regarding changes to New Hampshire’s Env-A 1400 rule in a 4TR article…it may ultimately become a webinar, so stay tuned!

Cycling is one of your passions. What rides are on your fall bucket list?

Great question – so hard to narrow the choices down! Lately, I’ve been enjoying riding a new “gravel bike” on dirt roads, jeep roads, snowmobile trails, and even mountain bike trails (at least the smooth ones). There are quite a few Vermont dirt roads and trails I’ve yet to explore on my gravel bike. When I’m not watching my kids’ soccer games, I’ll spend my free time taking a ride. The more off-road, the better!

What three words would your teenagers use to describe you?

I polled them and got a range of “creative” answers. Figures! I should have known given my sense of humor. Here’s the Rated G version: funny, caring, and a good listener.

To learn more about John, please visit his profile. You can reach him at jhinckley@all4inc.com // 610.422.1178

ALL4 is part of the New Hampshire Business & Industry Association

Changes to Oil and Gas General Operating Permits in Texas

Big changes are coming for oil and gas general operating permits (GOPs) in Texas – are you ready for them? Will these changes apply to your site? Don’t wait around until it’s too late; you only have until January 13, 2021 to review your GOP and submit an authorization to operate (ATO) application to revise it. This article will provide you a high-level overview on the changes and help you plan the next steps for compliance at your site.

Background

In Texas, a GOP is a type of Federal Operating Permit (FOP) that has a streamlined application and permitting process for sources of air emissions. GOPs can only be used by sites which have similar operations, emissions units, and applicable regulations. There are four GOPs (511, 512, 513, and 514) which cover upstream and midstream oil and gas sites, each with different requirements based on the county in which the site operates. Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) has proposed changes to these GOPs which are scheduled to become effective on October 15, 2020. Affected oil and gas sites will need to submit a revision to their GOPs via ATO applications to TCEQ after October 15, 2020 and no later than January 13, 2021.

What’s changed?

The biggest change to the oil and gas GOPs is the addition of multiple permitting tables, which list the requirements for specific unit. For example, TCEQ will be adding permitting tables for 40 CFR Part 60, Subparts OOOO and OOOOa (Standards of Performance for Crude Oil and Natural Gas Facilities) to oil and gas GOPs if the proposed changes are finalized. Sites with storage vessels, gas sweetening units, wells, and fugitive emissions that are subject to these two Federal regulations will be affected. Additionally, a permitting table will be required for process heaters subject to 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart DDDDD (National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants for Major Sources: Industrial, Commercial, and Institutional Boilers and Process Heaters).

A new periodic monitoring option is available for acid gas only flares that are subject to opacity emissions limits as stated in 30 Texas Administrative Code (TAC) §111.111(a)(4). This monitoring option requires quarterly visible emissions observations. Opacity and visible emissions monitoring are similar to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Reference Test Methods 9 and 22, respectively. This option will be added to the periodic monitoring option tables as PMG-OG-PM-001 and provides sites another monitoring option to streamline their application.

For GOPs 511 and 512, surface coating permitting tables will be added. This change will affect oil and gas sites subject to 30 TAC Chapter 115, Subchapter E, Division 2 in Dallas-Fort Worth, El Paso, and Houston-Galveston-Brazoria areas and in Gregg, Nueces, and Victoria Counties. The main units that will be affected are storage tanks, but other units such as engines may be affected as well.

These are the main changes for GOPs. Additional changes such as the removal of certain regulatory references, index number changes, and administrative changes have also been proposed by TCEQ. The proposed changes for each GOP can be found on TCEQ’s Title V Operating Permits Announcements page, here.

What do I need to do?

Once the changes to the GOPs become effective on October 15, 2020, each affected site must revise their GOPs by submitting an ATO application. Affected sites may continue operations before a new ATO is granted if the permit holder meets the following requirements as per guidance from the TCEQ:

- The permit holder complies with 30 TAC Chapter 116, all applicable requirements, all state-only requirements, and provisional terms and conditions.

- The permit holder maintains, with the authorization to operate under the general operating permit, the application until a new authorization to operate is granted.

- The permit holder operates under the representations in the general operating permit application.

The January 13, 2021 deadline is quickly approaching and does not allow a lot of time for site to submit GOP revisions. Thus, ALL4 is here to help and alleviate some stresses that this tight deadline might cause you, or your site.

Be on the lookout for TCEQ’s official announcement of the effective date of the GOP revisions on this page. If you have any questions regarding this blog or about changes to oil and gas GOPs, contact us.

Final Rulemaking to Address Reclassification of HAP Major Sources as Area Sources

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) has finalized its July 26, 2019 proposal to revise the 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart A General Provisions to include requirements for facilities that want to reclassify from a major source of hazardous air pollutants (HAP) to an area source. This rulemaking follows a January 25, 2018 U.S. EPA memorandum titled “Reclassification of Major Sources and Area Sources Under Section 112 of the Clean Air Act.” With the memo and rulemaking, U.S. EPA has formally reversed its longstanding “Once In, Always In” (OIAI) policy and coined a new acronym: Major Maximum Achievable Control Technology (MACT) to Area (MM2A). The rule should be published in the Federal Register soon.

The former OIAI policy was set out in a 1995 John Seitz memo and stated that a major source of HAP had only until the first substantive compliance date of an applicable MACT standard to reclassify as an area source. After that time, once a MACT standard applied to a facility, it always applied. Even if a facility was subsequently determined to be an area source, it could only avoid MACT compliance obligations under future major source rules. The current administration determined that the OIAI policy is not consistent with a plain reading of the Clean Air Act because the definitions of major source and area source lack any reference to the compliance date of major source requirements and there is no other text that indicates a time limit for changing between major and area source status. The January 2018 memo repealed the policy and U.S. EPA has now codified procedures for reclassifying from major source to area source (and vice versa) in the 40 CFR Part 63 General Provisions. Formally codifying the change in policy ensures that it will be implemented consistently by state and local agencies.

The following changes are being finalized:

- U.S. EPA is adding a new paragraph §63.1(c)(6) that states a major source can become an area source at any time by reducing its emissions of, and potential to emit (PTE), HAP to below the major source thresholds.

- Until the reclassification to area source status becomes effective (e.g., is included in a revised air permit), the source remains subject to the major source requirements. After the reclassification becomes effective, the source is subject to any applicable 40 CFR Part 63 area source requirements, including any requirement to make an initial notification.

- A major source that becomes an area source must meet applicable 40 CFR Part 63 area source requirements immediately (provided the first substantive compliance date for area sources has passed).

- A major source that becomes an area source and then later becomes a major source again must comply with applicable major source MACT requirements immediately (including any necessary updates to an initial notification).

- Reclassification does not absolve a source subject to enforcement action or investigation of any compliance obligations.

- Sources that obtain enforceable PTE limits in order to reclassify are required to keep the applicability determination records as long as they rely on the PTE limits to be area sources.

- Sources that reclassify in either direction must notify U.S. EPA electronically via the Compliance and Emissions Data Reporting Interface (CEDRI) after the effective date of the rule. Note that this requirement applies to any source that has reclassified since January 25, 2018.

- U.S. EPA is amending §63.13 to clarify that when Part 63 requires submittal of a report or notification to CEDRI the obligation to report to the U.S. EPA Regional office is fulfilled.

U.S. EPA is also proposing to revise individual subparts under 40 CFR Part 63 that currently specify dates that would conflict with the MM2A revisions and to include new citations in each rule’s general provisions applicability table.

U.S. EPA had proposed to require limitations on PTE to be legally and practicably enforceable and add definitions of those terms at §63.2. However, they received significant comments on these proposed changes and are still considering them. U.S. EPA is making a “ministerial” change to the definition of PTE at §63.2 by removing the word “federally” to address the outcome of a court decision that required U.S. EPA to explain why PTE limits must be federally enforceable. Permitting agencies and facilities should continue to rely on the historical U.S. EPA guidance relating to PTE and PTE limits.

The policy change and rulemaking are meant to provide a mechanism for sources to reduce their regulatory burden and an incentive for facilities to implement pollution prevention measures or enhanced air pollution control technologies in order to reduce emissions to below major source levels. U.S. EPA anticipates facilities will investigate reformulation of materials to contain less HAPs and more efficient, cleaner technologies and estimates the final rule will result in annual cost savings of $90 million. ALL4 recently assisted a facility with reclassification as they reconfigured their operations and significantly reduced emissions. The revised Title V permit has resulted in reduced regulatory burden (we eliminated requirements for three major source MACT standards) and we also took the opportunity to update and streamline the facility’s air permit compliance tools.

The rule is simply removing the timing requirement of the OIAI policy, under which sources could only reclassify if they took a PTE limit prior to the compliance date of the MACT standard. U.S. EPA reviewed permits for 69 major sources that have reclassified as area sources as a result of the change in policy and determined that 68 of the facilities would continue to employ the same compliance methods used to comply with the major source MACT rules, preventing emissions increases. U.S. EPA did not finalize any regulatory language that would prohibit an increase in emissions, however. They estimate that 7,187 facilities are subject to major source MACT rules.

Although reclassification can potentially provide a significant reduction in regulatory burden, as you are considering the implications of reclassification, keep in mind that there could be other requirements that become applicable when a major source MACT standard no longer applies. These could include area source standards under 40 CFR Part 63 or state air toxics rules. You should also consider the potential for future expansion or contraction of the facility and the implications of a requirement to immediately comply with the relevant 40 CFR Part 63 standard upon the effective date of reclassification. U.S. EPA did not finalize language allowing for any amount of time to come into compliance with either area or major source MACT requirements, so you should not reclassify until you are ready to comply with the requirements imposed by the reclassification. Finally, you should consider whether accepting HAP PTE limits in your permit will result in requirements for additional monitoring, testing, and recordkeeping to demonstrate that emissions remain below the major source thresholds. Conducting a site-specific analysis, developing a compliance strategy, and obtaining the requisite air permit revision will take time. The pros and cons of major versus area source status should be carefully considered, but can result in a reduction in burden and present a good opportunity to streamline compliance requirements and tools. Contact your ALL4 project manager or Amy Marshall with questions or for assistance with strategizing and permitting. If you have already reclassified since January 25, 2018, take note of the new requirement to submit a notification in CEDRI after the rule is published in the Federal Register.

The Fifth Revision of the TCEQ’s Penalty Policy

Even the mention of a penalty provokes worry in the minds of regulated entities. Now, what would happen if penalties were raised? The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) recently opened the public comment period on proposed Penalty Policy changes –which will result in higher fees and more violation events. These changes were motivated by recent incidents that have caused significant public and environmental impact in Texas.

Penalties are evaluated by the TCEQ using percentages of a maximum penalty. Each violation in an enforcement action is categorized as:

- Actual Release

- Potential Release

- Programmatic

The violations are further broken down as major, moderate and minor harm within each category above. The determined percentage is multiplied by the highest penalty amount for the statute and this becomes the base penalty amount. Changes to these percentages can have a significant impact on the total base penalty for enforcement. The following sections outline the changes and potential impacts of the revision to the TCEQ Penalty Policy.

Changes

Proposed changes to TCEQ’s Penalty Policy include increased percentage penalties for actual releases and potential for major and minor sources, increased percentage penalties for programmatic violations, increased frequency of penalties for continuous violations events, and inclusion of a penalty enhancement for emissions events that can be enforced in counties with a population of 75,000 people or more.

- For major sources actual release events, the statutory maximum penalty recommended for moderate and minor harm will increase from 30 to 50% and 15 to 30% respectively. The base penalty amount will increase due to this change.

- For minor sources actual release events, the statutory maximum penalty recommended for major, moderate, and minor harm increase from 30 to 50%, 15 to 25%, and 5 to 15% respectively. The base penalty amount will increase due to this change.

- For programmatic major violations, the recommended statutory maximum penalty will increase from 15 to 20% for major sources and 5 to 10% for minor sources. The base penalty amount will increase due to this change.

- For continuous events that do not have a daily frequency period, frequency periods will increase by one step (i.e., single events will be tracked quarterly, quarterly events will be tracked monthly, and monthly events will tracked weekly). The smaller evaluation time period will likely result in a higher total penalty for continuous events.

- For sites which have violation events in counties with a population of 75,000 or more, a penalty enhancement of up to 20% can be enforced.

In addition to the changes listed above, the proposed Penalty Policy changes affect dry cleaners, aggregate production operations, and underground petroleum storage tanks.

- For dry cleaners that are not registered, a penalty up to $50 per day will be issued for every day after the 30th day registration fees are due. The same penalty applies to late dry cleaner registration applications for every day after the 30th day the application must be submitted.

- For aggregate production operations that operate without registration, the yearly penalty will increase from $10,000 per year to $20,000 per year. The maximum total penalty will increase from $25,000 to $40,000.

- For facilities that have underground petroleum storage tanks on site, major source designation will increase from 50,000 gallons per month to 100,000 gallons per month.

Next Steps

The public comment period for these changes began on September 30, 2020 and will continue until October 30, 2020. Contact information, a link to the proposed changes document, and more information can be found on the TCEQ’s website here. If you have any questions about these upcoming Penalty Policy changes or the public comment process, contact us.

Texas Toxics Effects Screening Level (ESL) for Air Quality Impacts Analysis

Effects Screening Levels (ESLs) are used by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) to determine when a more in-depth review of air toxics modeling is necessary. The human health and welfare effects evaluation is an integral part of the air permitting process in Texas. For case-by-case permits including minor and major sources, prevention of significant deterioration (PSD), and nonattainment new source review (NNSR), TCEQ requires an air toxics impacts analysis for air contaminants based on the ESLs for the respective air contaminants. ESLs are comprised of short-term (1-hour average) and long-term (annual average) concentrations for various toxics. The primary focus of this blog is to provide guidance for air toxics modeling in case-by-case and amendment applications where offsite concentrations are over the ESL, and when they are under the ESL.

An air toxics impact analysis must be performed for any site that has the potential to emit a substance that is included on, but not limited to, TCEQ’s ESL list. TCEQ’s ESL list changes often, so it is important to obtain the most recent ESL list for air contaminants which may be involved in an air permitting project. To do this, follow TCEQ’s instructions on how to download the ESL list from the Texas Air Monitoring Information System (TAMIS) database. If a chemical is not found from TAMIS, you can request ESL values by sending a form to TCEQ’s toxicology group.

TCEQ uses a Modeling and Effects Review Applicability (MERA) analysis to determine if an in-depth review is required. The MERA is a nine-step (steps 0 to 8) analysis that determines the scope of air dispersion modeling and effects review and is documented in TCEQ’s MERA guidance document titled “Modeling and Effects Review Applicability (MERA)”. The key to correctly completing the MERA analysis is to determine at which step a chemical “falls out” of the MERA, which is done by evaluating the criteria of the certain step. The MERA begins with analysis of the net potential emissions increase and increases in complexity from project potential emissions to site-wide modeling. Modeling can be performed at any point after step 3 and is a requirement starting on step 7. For chemicals which do not “fall out” before step 7, a site-wide air toxics modeling analysis must be performed following TCEQ’s Air Dispersion Modeling Team (ADMT) guidance.

When a project air toxics modeling analysis is performed and reveals off-site concentrations below the levels listed in the table within the MERA reference guide step 4 for Maintenance, Startup, and Shutdown (MSS) and production emissions, no further analysis is required. When a site-wide air toxics modeling analysis is performed and reveals off-site concentrations below the ESL, there is no further analysis required. The MERA analysis, along with any site-wide air toxics modeling files, are then ready to be submitted to TCEQ with the rest of the air permit application or amendment. For site-wide modeling only, TCEQ’s Toxicology Division will then evaluate the modeling based on a three-tiered approach, which is outlined in Appendix D of TCEQ’s MERA guidance document.

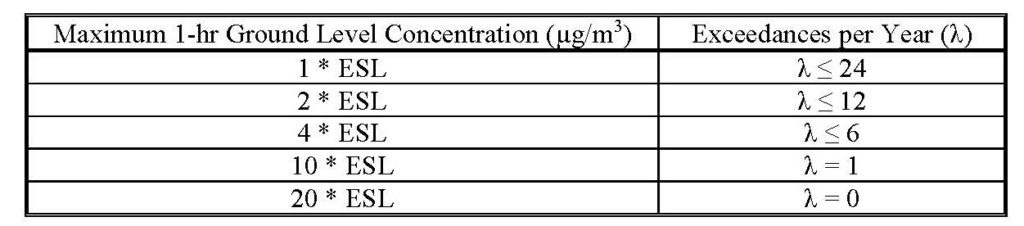

When the results of an air toxics modeling analysis are greater than the short-term ESL for a substance due to MSS emissions, there may still be a way to avoid an in-depth review. TCEQ allows some exceedances to the short-term ESL. Planned MSS emissions for certain compounds may exceed the ESL a certain amount of times, depending on the magnitude of the ESL exceedance. The number of allowable exceedances is determined using the following table from MERA step 5B:

For modeling scenarios that exceed the ESL and do not meet the criteria for these exceptions, an in-depth review will be required. An in-depth review is the third tier of the Toxicology Division’s evaluation procedure (Appendix D of TCEQ’s MERA guidance document) in which they consider the health and welfare impacts of the compound to determine if the impact is acceptable, allowable, or unacceptable.

For more information or if you have any questions regarding this blog, please reach out to our team at info@all4inc.com.