Hazard Alert: OSHA Steps Up Enforcement As Extreme Heat Endangers Workers Across the Nation

On July 27, 2023, President Biden requested the Department of Labor (DOL)’s Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) to issue a first-ever Hazard Alert for heat. This Hazard Alert reminded employers of their responsibility to protect workers from heat, to reaffirm worker rights, and to note upcoming federal enforcement actions.

Hazard Alert for heat explains how workers can notify OSHA of safety violations and details whistleblower protections. It includes resources and OSHA current/future actions on heat-related issues, including compliance assistance.

The alert is one of two measures the Biden administration is taking to help combat heat-related issues in the workplace. The other is increased inspections in high-risk industries such as construction and agriculture.

Background

In October of 2021, OSHA began heat-specific workplace rulemaking by publishing the document, Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings in the Federal Register. During the comment period, over 1,000 comments were received, which OSHA is reviewing prior to publishing any draft rules.

According to the hazard alert issued on July 27, employers should also:

- Give new or returning employees a chance to gradually acclimatize to high-heat conditions, provide training and plan for emergencies, and monitor for signs/symptoms of heat-related illness.

- Train employees on heat-related illness prevention, signs of heat-related illness, and how to act if they or another employee appears to be experiencing a heat-related illness.

In accordance with OSHA’s regulation at 29 CFR Part 1904, employers with more than 10 employees in most industries are required to keep records of occupational injuries and illnesses that occur in the workplace, including injuries and illnesses caused by heat exposure.

Resources

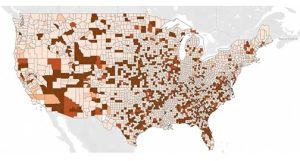

- As detailed in ALL4’s Cindy Castillo’s recent 4 The Record article, heat exposure in the workplace during the summer months can lead to serious injuries or even death. To increase awareness about heat illnesses and injuries, the Department of Health and Human Services recently published an interactive EMS HeatTracker map on the National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) website in partnership with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. It displays heat-related EMS activations at national, state and county levels and breaks down patient data by age, race, gender and location. This tool can be used to identify regions that are more prone to such illnesses.

- OSHA, in partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently published an infographic reminding workers to drink a cup of cool water every 20 minutes, take rest breaks in the shade or another cool location, and to know the sings of heat illness.

- The OSHA-NIOSH Heat Safety Tool is a useful resource for planning outdoor work activities based on how hot it feels throughout the day. It has a real-time heat index and hourly forecasts specific to your location. It provides occupational safety and health recommendations from OSHA and NIOSH. The tool also allows workers and supervisors to calculate the heat index for their worksite, and, based on the heat index, displays a risk level to outdoor workers. Then, with a simple “click,” you can get reminders about the protective measures that should be taken at that risk level to protect workers from heat-related illness-reminders about drinking enough fluids, scheduling rest breaks, planning for and knowing what to do in an emergency, adjusting work operations, gradually building up the workload for new workers, training on heat illness signs and symptoms, and monitoring each other for signs and symptoms of heat-related illness.

- HEAT.gov lists a variety of tools and websites that can be used to educate and prevent against heat related illnesses and injuries.

Next Steps

The best ways companies can continue to prevent heat-related illnesses or injuries include developing a written Heat Illness Prevention Plan, providing training to appropriate facility personnel, and implementing good heat safety practices as described in the OSHA-NIOSH Heat Safety Tool.

ALL4 will continue to monitor as OSHA and the Biden Administration promulgates workplace and heat injury and illness-related regulations. ALL4 has experience in assisting clients with developing OSHA program plans and assisting in implementation of those plans. ALL4 can partner with you to develop strategies for maintaining compliance as new regulations develop. If you would like to discuss your project or have any questions, please reach out to your ALL4 Project Manager or to Corey Prigent at cprigent@all4inc.com.

The Early Bird Gets the Worm: Preparing for Enhanced Flare Monitoring in the Chemical Sector

In case you haven’t heard yet, the U.S. Environmental Protection agency (U.S. EPA) has proposed revisions to the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) and New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) applicable to facilities in the Synthetic Organic Chemical Manufacturing Industry (SOCMI) and Group I and II Polymers and Resins (P&R) Industries. Check out ALL4’s previous blogs for a summary of the broader changes. This article is going to focus on a smaller chunk of those revisions, specifically, getting your facility ready to implement the proposed changes to the flare monitoring requirements in 40 CFR Part 63 Subparts F, G, H, and I (HON) and Subpart U (P&R Group I).

If there’s one thing we’ve learned from implementing changes to flare monitoring from the Refinery Sector Rules – it’s never too early to start planning ahead! The sooner you finalize your facility’s flare strategy and begin implementation of the monitoring systems, the better off you’ll be.

But where do I start?

Good question. There are many items to consider when developing a flare strategy, but a few of the most important pieces include:

- Are the new rule requirements different from my permit or my consent decree?

- What monitoring technology will be best suited for your operations?

- Will your facility’s data acquisition and handling system (DAHS) need upgrades/additional configuration to be able to demonstrate ongoing compliance?

- Do you have the resources needed for a robust quality assurance and quality control (QAQC) program?

- How will you comply with the recordkeeping and reporting requirements?

Great, but I have time, right?

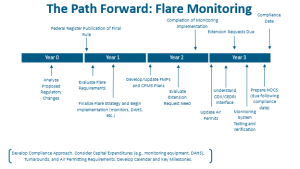

ALL4 has participated in several successful flare monitoring projects from the initial flare strategy planning all the way through implementation and verification of the monitoring systems. In our experience, this process can take 2-3 years on average to successfully complete. Take a look at the timeline below – there’s a lot to fit in!

An important piece that may be easy to overlook is building in the time necessary for testing and troubleshooting prior to the compliance date. You’ll want to plan for a period of time to allow the monitoring systems to collect data, the DAHS to handle and report the data, and the environmental and operational staff to review and evaluate the data and monitoring systems.

If you have questions or would like to discuss approaches for upgrading your flare monitoring programs, please reach out to me at kfritz@all4inc.com or 610-422-1116. We will also be hosting a complimentary in-person workshop for members of industry in Lake Charles, LA on November 8, 2023, to provide an overview of the proposed changes and will touch on flare monitoring impacts. ALL4 is monitoring all updates published by the U.S. EPA on this topic, and we are here to answer your questions and assist your facility with any aspects of environmental regulatory compliance.

New Jersey Environmental Justice Rule Public Participation and Implications

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) published the final Environmental Justice Rule (EJ Rule) on April 17, 2023. The EJ Rule (N.J.A.C. 7:1C) was promulgated in response to New Jersey’s Environmental Justice Law (EJ Law) that was signed into effect in September 2020. Facilities subject to the EJ Rule must hold “meaningful public participation” as part of the EJ Rule process. Read on to learn more about what is involved in the public participation requirements and what impacts it may have on your facility’s permitting process.

General Overview of the EJ Rule

Compliance with the EJ Rule can be broken down into the following steps. You can read more about the overall structure and applicability of the EJ Rule here.

- Determine Applicability

- Initial Screen

- Determine Application Requirements

- Develop Environmental Justice Impact Statement (EJIS)

- Meaningful Public Participation

- NJDEP Review

- NJDEP Decision

Each applicant subject to the EJ Rule must prepare an EJIS along with supplemental information, as applicable. N.J.A.C. 7:1C-3.2 describes the information required in the EJIS, including initial screening information, an assessment of facility impacts to environmental and public health stressors, a public participation plan, and other details pertaining to the facility. Supplemental information, as described at N.J.A.C. 7:1C-3.3, may be required if the overburdened community (OBC) is already subject to adverse cumulative stressors or if the facility cannot demonstrate that it will avoid a disproportionate impact.

Once the EJIS is reviewed and approved, NJDEP will post the EJIS online and the facility may then move forward with the public participation steps. There are three elements to the public participation process:

- Public Notices

- Public Hearing

- Public Comment Period

Public Notices

Public notices must be first submitted to NJDEP’s Office of Permit and Project Navigation (OPPN) for review. The notice must include:

- The name of the applicant;

- The date, time, and location of the public hearing, including virtual attendance instructions;

- A summary of the project;

- A facility location map;

- A brief summary of the EJIS and information on how to access the EJIS;

- A copy of the application(s) and authorization(s) (current and pending) associated with the project;

- The start and end dates of the 60-day public comment period;

- An email or mailing address for submitting comments;

- OPPN’s mailing address for submitting comments; and

- A statement inviting participation in the public hearing.

The public notice must be provided to NJDEP, the governing body and clerk of the municipality in which the OBC is located, property owners within 200 feet of the facility, and local environmental and EJ bodies. The notice also must be published in at least two newspapers circulating within the OBC and posted on a sign at the facility’s location. Additionally, the applicant is required to develop a community-specific engagement plan to employ additional notice methods, as necessary, to ensure that all individuals in the OBC receive direct and adequate notice. Public notices may need to be provided in non-English languages commonly spoken in the OBC.

Public Hearing

The applicant must conduct a public hearing in the OBC that is affected by the facility’s operations. In the public hearing, the applicant should present the EJIS to the members of the OBC to explain operational information, the environmental and public health stressors affecting the OBC, and how the facility proposes to avoid or minimize impacts to the affected stressors. There are many important factors to consider when planning and conducting a public hearing, as addressed in the following subsections.

Location and Timing

The public hearing must be conducted during a weekday, beginning no later than 6:00 PM. The community must be notified of the hearing at least 60 days before the scheduled date. The hearing must be held in-person at a suitable location in the OBC, while also providing a virtual attendance option. The hearing must be recorded and officially transcribed, and this information must be made available online following the hearing. NJDEP also recommends having a moderator for hearings anticipated to have a high attendance rate.

Accessibility

NJDEP recommends using interpreters in communities that speak multiple languages. The content presented must be visually and auditorily accessible to all attendees; therefore, NJDEP recommends the use of microphones. The applicant is also required to provide copies of the EJIS, public notices, and other supporting materials in languages commonly spoken in the OBC. Closed-captioned and translation tools in virtual meeting programs (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams) are also recommended to promote accessibility for attendees.

Presentation Content

The purpose of the public hearing is to present the content of the EJIS to the OBC in a clear, concise, and accessible manner, and to allow for members of the OBC to comment and ask questions. The hearing should be extended for as long as reasonable to allow all community members to comment.

Public Comment Period

Applicants must hold a 60-day public comment period that remains open at least 30 days after the public hearing is held. The applicant must then provide NJDEP with responses to all comments received.

The public participation requirements can add a significant amount of time to your facility’s permit review process. It is important to start planning early for the public hearing and communicate with NJDEP throughout the process to ensure that you are meeting all of the requirements.

If you have questions or need assistance planning for compliance with the NJ EJ Rule, please contact Sarah Raver at sraver@all4inc.com or (610) 422-1161.

Michigan Regulates PFAS via NPDES

On March 14, 2023, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE or department) published an interoffice communication summarizing a comparison of the department’s current strategy for using the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to regulate the discharge of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with that of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). The communique outlined two of the primary sources of PFAS being discharged directly to surface waters: industrial facilities and municipal publicly owned treatment works (POTW). In the same month, EGLE published revisions to guidance documents for NPDES permitting strategies around these two sources, which provide additional insight into what PFAS limits, monitoring and reporting requirements, and enforcement will look through the lens of the NPDES program in Michigan.

Background

In February 2018, at the recommendation of their Wastewater Workgroup, the EGLE launched the Industrial Pretreatment Program (IPP) PFAS Initiative, which prompted investigative activities such as conducting point source monitoring, targeted sampling, and identification of significant sources of PFAS in surface waters. Note that EGLE was previously the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), which appears in this and other publications from the department before April 22, 2019. The following year, the Surface Water Workgroup began sampling surface waters around the state and continued at an increasing pace through 2022. Based on the monitoring results and Michigan’s Part 57 Rule (MCL §323.1057), which allows for narrative methods in the development of Water Quality Values (WQV) protective of human health and aquatic life, WQV for the following three PFAS were either revised or published for the first time:

| Human Noncancer Value (HNV) [Nanograms per Liter (ng/L)] |

||

| Chemical | Drinking | Nondrinking |

| Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS) | 11 | 12 |

| Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) | 66 | 170 |

| Perfluorobutanesulfonic Acid (PFBS) | 8,300 | 670,000 |

As a result, water quality-based effluent limits (WQBELs) for surface water discharges of toxic substances, based on Michigan’s Part 8 Rules (MCL §§323.1201-1221), can be developed for receiving waters and will be incorporated into permit limits going forward. However, based on the high concentrations and prevalence identified by surface water monitoring, EGLE chose to focus on PFOS in developing a permitting strategy for POTW. The department then developed and published an online mapping tool for identifying municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), which is another way to describe a POTW, and categorizing them by PFAS source classification. The Michigan IPP WWTP PFAS Status tool categorizes these WWTP by EGLE’s new classification system, which directly relates to the regulatory requirements for that facility and service region.

Publicly Owned Treatment Works

The classification system that EGLE has developed for determining monitoring requirements for WWTP is outlined in the Municipal NPDES Permitting Strategy for PFOS and PFOA. The new system categorizes facilities into “Bins” based on the results of effluent testing as well as the potential of their Industrial Users (IU) to be contributing sources of PFOS, the most prevalent PFAS based on the monitoring data collected. These Bin classifications are outlined in Table 1:

Table 1

Bin Categories for WWTP with PFOS

| Bin | IU Sources Present | PFOS Effluent Data > WQBEL | PFOS Effluent Data (ng/L; ppt) |

| 3b | Yes | Yes | ≥ 50 |

| 3a | Yes | Yes | 13-49 |

| 2 | Yes | No | ≤ 12 |

| 1 | No | No | < 12 |

These criteria are straightforward and objective; however, another more subjective factor, reasonable potential, is implemented in concert with the criteria above. Bin 3a or 3b designations appear to be the least subjective category, reserved for facilities that have IU sources and WWTP effluent data that supports high levels of PFOS passing through the treatment system. Bins 2 and 1, on the other hand, are subject to less frequent monitoring and are not all immediately subject to pollutant minimization, source evaluation, or corrective action plans. Instead, the guidance indicates that outside of some routine monitoring for all Bins there would only be additional requirements imposed if a triggering event occurs. A triggering event will most likely be defined as an exceedance in WQBELs during routine monitoring, but it is not unreasonable to think that EGLE could justify further action based on a different, more qualitative definition of a triggering event.

Direct Discharges from Industrial Sources

Industrial facilities (e.g., manufacturing, utilities, transportation) that discharge wastewater or storm water, and have been identified as known or suspected sources of PFAS, can expect to have monitoring, reporting, or even voluntary administrative consent orders associated with their next permit renewal. According to Table 1 of the communique, the following types of facilities have been identified thus far:

- Metal Finishing

- Airports and Military Installations

- Landfills

- Chemical Manufacturers

- Petroleum Refineries

- Bulk Fuel Transfer Facilities

- Pulp & Paper Manufacturers

- Automotive Manufacturing Facilities

EGLE makes it clear that a facility’s industrial category will not preclude them from PFAS regulation, or in other words, no facility is off the hook. The industrial wastewater and storm water guidance goes on to say that when PFAS is not a requirement of a facility’s current permits, and neither the facility or EGLE knew of the presence of PFAS at that time, then the presence of PFAS in a discharge is not a violation. In this scenario, EGLE suggests that voluntary administrative consent orders (ACO) will be the preferred resolution, but firmly outlines how the failure of a facility to enter into the ACO could result in revocation of permits and ultimately enforcement action for unauthorized discharges.

Regardless of industrial activity or size, the department has promised regulation of PFAS sources discharging to surface waters, specifically stating that limits will be incorporated into any NPDES permits issued after October 1, 2021, and can be anticipated to expand that where it hasn’t already. ALL4 has confirmed that these limits have already been implemented into municipal permits and those municipalities have implemented PFAS into their respective IU permits.

What Actions Should You Take

The significance of upcoming PFAS regulations is widely discussed, although rarely clear. In this case, however, it is abundantly clear how EGLE is planning to establish and enforce wastewater and stormwater discharge limitations on industrial and municipal dischargers. Whether your facility discharges directly to surface water or a POTW, if the facility has been identified as a source of PFAS, then it is highly likely that PFAS limits will be implemented into your next NPDES permit. If you have not been identified as a source, but your facility is in one of the industries mentioned above, then it’s more than likely that EGLE will want to discuss PFAS during your next permit renewal cycle.

It’s critical for your facility to determine whether PFAS discharge limits will be implemented in your wastewater or stormwater permit(s). If your facility has already been issued PFAS discharge limits, or has been subject to enforcement actions, identifying the source of PFAS at your facility, treatment or disposal options, and alternatives for PFAS-containing process materials is crucial for compliance. In either case, developing and executing a sound strategy around PFAS discharges could be the difference between maintaining permit compliance and harsh permit requirements, fines and violations, and public notices.

ALL4 is well positioned to provide strategic support in the form of sampling and analysis plans, PFAS alternatives assessments, treatment or disposal investigations, and implementation of permitting strategies. ALL4 will continue to monitor regulatory developments regarding PFAS in Michigan and at the federal level. If you are looking for guidance or have questions on navigating upcoming permitting or compliance issues around PFAS, please contact Cody Fridley at 269.716.6537 or CFridley@all4inc.com, or Tia Sova at TSova@all4inc.com.

Proposed Revisions to the “Guideline on Air Quality Models”

On October 23, 2023, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) published a proposed rule to revise 40 CFR Part 51, Appendix W (the “Guideline on Air Quality Models” or “Guideline”). The proposed revisions include enhancements to the formulation and application of the U.S. EPA’s preferred near-field air dispersion model (AERMOD) and its meteorological pre-processor (AERMET), and updates to the recommendations for development of representative background concentrations for cumulative National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) air quality modeling demonstrations. The 13th Conference on Air Quality Modeling, mandated by Section 320 of the Clean Air Act (CAA), scheduled for November 13-14, 2023, at U.S. EPA’s RTP, NC Campus will serve as the public hearing where public comments will be taken and placed in the docket. Public comments on the proposed revisions to the Guideline will be accepted through December 22, 2023.

The proposed regulatory updates to AERMOD include:

- Addition of a new regulatory non-default Tier 3 nitrogen oxides (NOX) to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) conversion option, the Generic Reaction Set Method (GRSM),

- Incorporation of the Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere Response Experiment (COARE) algorithms into AEMRET, and

- Addition of RLINE as a mobile source type.

GRSM NO2 Screening Option

The GRSM NO2 screening option was developed to address photolytic conversion of NO2 to nitrogen oxide (NO) and to address the time-of-travel necessary for NOX plumes to convert the NO portion of a plume to NO2 via titration and entrainment of ambient ozone. The existing Tier 3 NO2 options, Plume Volume Molar Ration Method (PVMRM) and Ozone Limiting Method (OLM), do not address these mechanisms and have been shown to overpredict ambient impacts within the first one to three kilometers (km) from the emissions source. To run the GRSM option, in addition to the NO2/NOX in-stack ratios and hourly ozone (O3) ambient monitoring data required for PVMRM and OLM, GRSM also requires hourly NOX ambient monitoring data. The hourly ozone and NOX ambient monitoring data must coincide with the hourly meteorological dataset utilized in the model. As a regulatory non-default option, the GRSM will be able to be used with prior approval of the regulatory jurisdiction and be another tool for NO2 modeling demonstrations.

COARE Addition

With the recent surge in offshore wind air permitting projects the proposed Guideline revisions include adding the COARE algorithms to AERMET for meteorological processing of observed or prognostic meteorological data in overwater marine boundary layer environments. The addition of COARE to AERMET will replace the current standalone AERCOARE program. Lastly, this revision would remove the current lengthy and tedious process of completing an alternative modeling demonstrate to utilize the COARE algorithms. However, use of the COARE algorithms will still require U.S. EPA Regional approval similar to the current process for utilizing Tier 3 NO2 non-default screening options.

RLINE Addition

Based on an Interagency Agreement between U.S. EPA and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) a new source type, RLINE, is being proposed to be added for regulatory modeling of mobile sources. Like COARE, RLINE was originally developed as a stand-along model known as the Research Line Model (R-LINE). The RLINE model was designed for near-surface releases to simulate mobile source dispersion focusing on the near-road environment. U.S. EPA has noted that RLINE does not replace the existing AREA, LINE, and VOLUME source types, so all four can be utilized for characterizing mobile source emissions.

General AERMOD Enhancements

In addition to the updates discussed above, a new proposed version of AERMOD (v. 23132) has been released which includes a slew of other bug fixes and general enhancements to improve the model. The new version of AERMOD can be used immediately for regulatory modeling demonstrations. However, the updates discussed above are considered regulatory and, therefore, won’t be able to be utilized until the Appendix W revisions are finalized.

Updates to Recommendations on the Development of Background Concentrations

U.S. EPA is proposing updates to Section 8 (Model Input Data) of the Guideline to refine the guidance for identifying ambient monitoring data to be utilized as part of NAAQS modeling demonstrations. The proposed updates are to address the current lack of specificity and inconsistent approaches regulatory agencies have implemented based on the lack of specificity. The proposed updates outline a framework that focuses on defining representative background concentrations through qualitative and semi-quantitative considerations. In addition, to the proposed updates to Section 8 U.S. EPA has also developed “Draft Guidance on Developing Background Concentrations for Use in Modeling Demonstrations.” The Draft Guidance outlines U.S. EPA recommended stepwise considerations designed to identify representative background concentrations for cumulative impacts analyses and to avoid conservative “double counting” of local sources. What the Draft Guidance does not address, or update, is the conservative approach of combining design value (e.g., Tier 1) or near design value (e.g., Tier 2) monitoring data with modeled design values.

Takeaways

The proposed revisions to the Guidelines provide some additional regulatory non-default options that will be useful in specific modeling applications (i.e., NO2 modeling, overwater modeling, mobile source modeling) and require less “hoops to jump through” by way of being regulatory approved. The updates to Section 8 related to identifying background concentrations and the supporting background concentration guidance document will have the broadest impacts and will be especially important with the pending proposal to lower the particulate matter less than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) annual NAAQS from 12 micrograms per meter cubed (µg/m3) to 9 µg/m3 or 10 µg/m3. However, the proposed revision doesn’t represent a stepwise improvement in the air quality modeling process and as a result regulatory air quality modeling will continue to be a difficult and critical step in the air permitting process. U.S. EPA has indicated they hope to finalize the revisions to the Guideline by Spring of 2024.

Several ALL4 staff will be in attendance at the 13th Conference on Air Quality Models on November 14-15, 2023, in RTP, NC. If you have any questions about how the proposed revisions will impact your facility or your next project, please contact Dan Dix.

U.S. EPA Hazardous Air Pollutant Permitting Process-Clarifications, Regulatory Updates, and Deadlines

U.S. EPA has proposed to amend the General Provisions for National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP). The proposed amendments relate to both to applicability and deadlines associated with the addition of a compound to the list of hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) under the Clean Air Act (CAA) and a facility’s classification for air quality permitting and regulatory purposes. The action (referred to as the HAP infrastructure rule) was proposed in the Federal Register on September 13, 2023 and can be found here. This action focuses on addressing the following three issues:

- Whether already promulgated NESHAP would apply to a newly listed HAP.

- Permitting implications for facilities that become major sources under CAA section 112 solely due to the addition of a new HAP to the HAP list (hereinafter Major Source Due to Listing or “MSDL” facilities).

- The applicable emission standards (e.g., new source standards or existing source standards) and the compliance deadlines for an MSDL facility that result from the applicability of a major source NESHAP1.

The CAA requires U.S. EPA and states with delegated authority to regulate emissions of HAPs. The original list from 1990 included 189 pollutants. Aside from a few clarifications and minor changes, that list has been relatively static. In fact, those changes were largely in the category of removals from the list. However, in January 2022 U.S. EPA issued a final rule to add 1-Bromopropane (n-propyl bromide or NPB) to U.S. EPA’s list of HAP; this was the first HAP addition to the list since it was developed over 30 years ago. If you are curious about this, see my article on that topic and some of the anticipated implications at the time.

How do I know if the HAP infrastructure action will impact me and to what extent?

The impact will vary from little or no impact to somewhat substantial impact (e.g., an air permitting action triggered) depending on your facility and its operations. Here are some thoughts that might help you consider if this impacts you.

- Am I currently a major source of HAP or an Area Source of HAP? If you are an area source, keep reading.

- Does my operation currently use NPB or another material that may be classified as a HAP in the future? If yes, keep reading.

- What are my current actual and potential HAP emissions, and do I have a Title V operating permit already?

If your facility is an area source of HAPs, and adding emissions from a newly listed HAP to current facility HAP emissions will cause facility-wide emissions to meet or exceed either 10 tons per year of an individual HAP or 25 tons per year for combined HAPs, the HAP infrastructure rule will impact your facility. A major source of HAPs is a facility with a potential to emit (PTE) at or above either 10 tons per year of an individual HAP or 25 tons per year for combined HAPs from the facility. In the previous example of an existing area source facility, not only will your facility become a major source under Title V of the CAA and require a Title V Operating Permit (if your facility is not otherwise required to have a Title V Operating Permit), you may become subject to major source NESHAP rules that did not previously apply. Complying with applicable requirements for a major source NESHAP can be complicated. Determining what requirements apply, developing an adequate compliance demonstration, and understanding implementation timing can have a large impact on operations (and sometimes capital costs).

What does the HAP infrastructure action mean to me?

There are several situations that could result in the need for a facility to take action. Some examples of requirements that you may need to meet include, but are not limited to, the following:

| If your facility emits the newly listed HAP: | You must add the new HAP to your facility’s PTE as of the effective date of the listing of the new HAP. |

| If your facility is a synthetic area source (e.g., one with permit limits on HAP emissions below major source thresholds): | You must evaluate whether your HAP emissions will remain below your permit limits and revise your permit, as necessary. |

| If your area source becomes a major source due to listing of a new HAP (e.g., your PTE now exceeds major source levels), you must either: | (1) obtain an enforceable limit on your HAP PTE to avoid major source status, or

(2) submit a Title V permit application within 12 months of becoming a major source. |

| If you are subject to an area source NESHAP and you become a major source due to listing of a new HAP, you must: | · Evaluate whether any major source NESHAP applies.

· Submit an initial notification for each newly applicable NESHAP. · Determine if a permit application is needed to comply with the newly applicable NESHAP. · Comply within the timeframe provided (U.S. EPA has proposed that the time required to comply will be based on the difficulty of complying with the newly applicable NESHAP and could range from 0 to 3 years). Facilities may request a 1-year extension to install controls. |

| If you emit a newly listed HAP, you should also: | Watch for changes to NESHAP to incorporate applicable requirements related to the newly listed HAP. |

Note that U.S. EPA has proposed that a newly listed HAP is not regulated under any NESHAP promulgated before the effective date of the listing of that new HAP. For example, if a new listed HAP is also a VOC and the NESHAP regulates VOC as a surrogate for organic HAP, or if a coating regulation limits the total HAP that may be contained in a coating, the newly listed HAP is not covered by the NESHAP until EPA reviews the rule and either establishes new standards or revises previous standards to include the newly listed HAP. EPA has also proposed that facilities that become MSDL are existing sources, not new sources, for purposes of determining which standards in a NESHAP might apply.

It’s important to note that requirements will be specific to your situation and there are other considerations besides those listed above. The implications of the rule, should it impact your facility after finalization, could fundamentally result in changes to how you operate (e.g., changes to applicable requirements and necessitating changes to your air quality operating permit). Due to this and the lead time to address the changes, the action warrants a strategic assessment of future business and operating plans as it relates to air quality-related regulations and permits. Should you have interest in preparing comments on the draft infrastructure rule, comments are due by November 13, 2023. U.S. EPA is likely to get significant comment on their proposed compliance timing requirements for MSDL facilities and will likely get requests to clarify requirements in situations they have not yet addressed. Note that U.S. EPA plans to address other related issues in the future, so this proposal is not likely to be the last thing you hear on this subject.

If you are curious about this topic and would like to discuss its potential impacts to your facility or need assistance preparing formal written comments, contact Nick Leone at nleone@all4inc.com or 610-422-1121.

1See U.S. EPA Federal Register Notice 62711: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-09-13/pdf/2023-19674.pdf

Proposed Changes to Storage Tanks New Source Performance Standards

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) recently proposed changes to the “Standards of Performance for Volatile Organic Liquid Storage Vessels (Including Petroleum Storage Vessels).” These changes to the New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) include proposed revisions to 40 CFR Part 60, Subpart Kb, applicable to sources that commenced construction, reconstruction, or modification after July 23, 1984, and a new Subpart Kc that will apply to sources that commence construction, reconstruction, or modification after October 4, 2023. U.S. EPA packed a significant amount of information and changes into about 20 pages of a Federal Register notice. This article provides an overview of the proposed amendments.

Applicability

40 CFR Part 60, Subpart Kb applies to storage vessels above certain capacity thresholds that store volatile organic liquids (VOLs) above a maximum true vapor pressure threshold. Subpart Kb contains another set of thresholds for storage vessels that require control. For Subpart Kc, U.S. EPA is proposing to eliminate the use of a vapor pressure threshold for regulated storage vessels and instead determine applicability based solely on the size of the storage vessel. U.S. EPA is, however, proposing to retain the vapor pressure threshold concept to determine which storage vessels must install controls. The tables below present the proposed applicability and control criteria.

Comparison of Rule Applicability Criteria

| Subpart Kb Applies to Storage Vessels… | Subpart Kc Would Apply to Storage Vessels… |

| With a capacity of 20,000 gallons or more that store VOL with a maximum true vapor pressure over 2.2 pounds per square inch absolute (psia), or

With a capacity of 40,000 gallons or more that store VOL with a maximum true vapor pressure over 0.5 psia. |

With a capacity of 20,000 gallons or more that store a VOL. |

Comparison of Control Requirement Thresholds

| Capacity (gallons) | Control is Required if the VOL Maximum True Vapor Pressure is Greater Than…(psia) | |

| Subpart Kb | Subpart Kc | |

| ≥ 20,000, < 40,000 | 4.0 | 1.5 |

| ≥ 40,000 | 0.75 | 0.5 |

U.S. EPA is proposing to carry over most of the exemptions specified 40 CFR §60.110b(d) to the new Subpart Kc, with the exception of storage vessels subject to 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart GGGG (National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants: Solvent Extraction for Vegetable Oil Production) on the basis that the proposed Subpart Kc improves upon Subpart GGGG. Consistent with Subpart Kb, the proposed definition of storage vessel in Subpart Kc does not include process tanks.

Control Requirements for Subpart Kc: Storage Vessels Containing VOL with a Maximum True Vapor Pressure less than 11.1 psia.

For new or reconstructed affected storage vessels that contain a VOL with a maximum true vapor pressure less than 11.1 psia, U.S. EPA is proposing to revise the existing Kb requirements in a new Subpart Kc such that an internal floating roof (IFR) must be equipped with either a liquid-mounted or mechanical shoe type primary seal and be equipped with a rim-mounted secondary seal. Gauge hatches and sample ports must be gasketed and guidepole configurations must incorporate the provisions outlined in the 2000 U.S. EPA Storage Tank Emissions Reduction Partnership program.

U.S. EPA is also proposing to update the requirements for an external floating roof (EFR) storage vessel used as an alternative to an IFR. U.S. EPA is proposing that:

- EFRs must have a primary and secondary seal as specified for IFRs, in addition to welded seams.

- If unslotted guidepoles are used, they must be equipped with gasketed sliding covers and pole wipers.

- If slotted guidepoles are used, a liquid mounted primary seal must be used and the slotted guidepoles must have a gasketed sliding cover, pole sleeve, and pole wiper.

Facilities that plan to use an EFR as an alternative compliance method should review the proposed Subpart Kc rule language for other equipment design requirements.

Similar to Subpart Kb, U.S. EPA is proposing to retain the option to use a closed vent system (CVS) and a control device as an alternative to using an IFR in Subpart Kc; however, the Agency is proposing to increase the required control efficiency from a 95% to a 98% reduction in emissions. Additionally, U.S. EPA is proposing requirements for design and operation of CVSs as detailed below for storage vessels that contain VOL with a maximum true vapor pressure of 11.1 psia or more.

New for Subpart Kc, a “modification” would include storing a VOL that has a higher maximum true vapor pressure than the VOL previously stored. This is contrary to U.S. EPA’s previous interpretation of the exemptions at 40 CFR §60.14(e)(4) that a change in the type of material stored was not a modification if the storage vessel was capable of accommodating the new material. There are sure to be numerous comments on this proposed change.

U.S. EPA is proposing that modified storage vessels that store a VOL with a maximum true vapor pressure less than 11.1 psia that do not have an EFR, or that do not route emissions to a control device, must meet the requirements for IFRs described above. If the modified storage vessel has an existing internal or external floating roof, it can alternatively meet the requirements of Subpart Kb for IFRs or EFRs, as applicable. If the modified storage vessel routes emissions to a control device, the source would be required to reduce inlet volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions by 98% or greater under Subpart Kc (Subpart Kb requires a reduction of 95%).

Control Requirements for NSPS Subpart Kc: Storage Vessels Containing VOL with a Maximum True Vapor Pressure of 11.1 psia or More.

For new, modified, or reconstructed storage vessels that contain a VOL with a maximum true vapor pressure of 11.1 psia or more, U.S. EPA is proposing that emissions must be routed through a CVS to a control device achieving at least 98% control, as opposed to 95% in Subpart Kb. Furthermore, U.S. EPA is proposing the following requirements for the storage vessels, CVSs, and control devices:

- The storage vessels must be designed and operated to have a gauge pressure no less than 1 psi greater than the maximum true vapor pressure of the VOL and anticipated back pressure.

- Vacuum breakers must have a close pressure of no less than 0.1 pounds per square inch gauge (psig) vacuum.

- Unless the CVS is operated under vacuum, the CVS must operate with “no detectable emissions” demonstrated by a leak definition of 500 parts per million by volume (ppmv) above background. U.S. EPA is proposing that sensory monitoring (e.g., visible, audible, olfactory inspection) be performed quarterly, and Method 21 monitoring be conducted at least annually.

- Bypasses of the CVS or control device must be monitored.

- Any pressure relief device must be equipped with a monitoring device to identify pressure releases, notify operators of a release, and record the time and duration of the release.

- If emissions are routed to a flare, U.S. EPA is proposing that the flare meet the requirements in 40 CFR §63.670 (i.e., the enhanced flare provisions in the refinery sector rule).

Monitoring Requirements for NSPS Subpart Kc

In addition to the monitoring requirements described above for CVSs, bypasses, and pressure relief devices, U.S. EPA is proposing several monitoring updates for Subpart Kc to ensure compliance with the emissions standards. These include monitoring the vapor concentration of the air space above IFRs against the lower explosive limit (LEL) annually to assess the condition of the IFR and closure systems. In addition, U.S. EPA is proposing that floating roofs be equipped with alarms to indicate when the roof is approaching the specified landing height. Other significant proposed updates to monitoring requirements include a requirement to repeat control device performance tests every 5 years and a requirement to establish and comply with operating parameter monitoring limits on a rolling 3-hour average basis.

Perhaps one of the most significant revisions to monitoring requirements compared to Subpart Kb is the proposed change to require periodic testing for liquid vapor pressure for all VOL of variable composition, instead of just waste mixtures, for tanks storing VOL that are subject to the rule, but not otherwise subject to control. As mentioned earlier in this article, U.S. EPA is proposing to eliminate the vapor pressure threshold criteria for Subpart Kc applicability. Thus, facilities storing VOL with very low vapor pressures but variable composition will be required to conduct physical testing for vapor pressure every 6 months.

Startup, Shutdown, and Malfunction Requirements for NSPS Subpart Kc

In addition to the changes described above, U.S. EPA is addressing startup and shutdown emissions through the application of degassing requirements for storage vessels complying with the CVS and control device option (or requirement), and for any vessel with a design capacity of 1 million gallons or more that contains a VOL with a maximum true vapor pressure of 1.5 psia or more. EPA is proposing that these storage vessels must be degassed to a control device that reduces VOC emissions by 98% or more.

U.S. EPA is not proposing any separate allowance or exemption for malfunction events. U.S. EPA explains in the preamble to the proposed rule that discretion will be used in the application of enforcement to malfunction events, and that sources are able to raise defenses in enforcement cases before a court.

Additional Changes and Compliance Dates

U.S. EPA is proposing additional changes for both Subparts Kb and Subpart Kc. These changes include updates to analytical methods and the use of electronic reporting. U.S. EPA is proposing the specified reports required under Subpart Kb be submitted as PDF documents to the Compliance and Emissions Data Reporting Interface (CEDRI). Under Subpart Kc, facilities would be required to use Microsoft Excel reporting templates to submit reports via CEDRI.

Additionally, in Subpart Kc U.S. EPA is proposing to supersede the semi-annual reporting requirements under 40 CFR §60.7. U.S. EPA is proposing separate semi-annual reporting requirements that include:

- Storage vessel and compliance option identification;

- Whether a storage vessel was inspected during the reporting period;

- Dates that storage vessels were last emptied and degassed;

- Identification and details regarding required inspections;

- Indications as to whether floating roofs were repaired, replaced, or taken out of service;

- Information related to landing of floating roofs;

- Inspections of CVSs and instances where a continuous monitoring system (CMS) indicates operation outside the range of an established monitoring parameter;

- Information on the operation of a flare used to control emissions; and

- Information on releases from pressure relief devices and bypasses.

These semi-annual reports would be due on a scheduled based on the date the storage vessel first becomes an affected source under Subpart Kc. This could potentially lead to multiple reporting timelines for facilities with more than one affected source, prompting facilities to consider using the procedures in 40 CFR §60.19 to adjust reporting deadlines.

U.S. EPA is proposing affected sources would be required to comply with the changes upon publication of the final rule. Comments on the proposed rule are due by November 20, 2023. The final rule should be signed by September 30, 2024.

What do the Proposed Changes Mean for You?

Although we’ve condensed them into a few paragraphs, there are numerous changes to the NSPS storage vessel requirements coming in the future. As described above, U.S. EPA is proposing the applicability of Subpart Kc would be triggered by the storage of a VOL with a higher vapor pressure than that currently stored; therefore, facilities should carefully read and understand the proposed requirements prior to changing their storage vessel service in case this requirement is finalized as proposed. Environmental professionals at facilities should communicate now with operations staff about the implication of such a service change to avoid being caught off-guard in the future.

Have questions about the new requirements? Or need help determining future permitting changes required as a result? Don’t hesitate to reach out to me, Philip Crawford at pcrawford@all4inc.com, or your ALL4 project manager for additional information.

Preparing for HON: Lessons Learned from Recent Petrochemical Rulemaking

On April 25, 2023, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) proposed revisions to several National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP), including 40 CFR Part 63, Subparts F, G, H, and I (referred to as the Hazardous Organic NESHAP, or HON). These revisions were a result of U.S. EPA’s required periodic technology review, a decision to conduct another risk review of the source category (due to concern over risk from emissions of ethylene oxide), and recent court decisions related to gap filling and startup, shutdown, and malfunction exemptions. Proposed revisions to the HON affect a variety of sources, including process vents, storage tanks, heat exchange systems, pressure relief devices, and flares. The proposed revisions would also add new fenceline monitoring provisions and define new standards for sources “in ethylene oxide service”. Check out this post by Chris Ward for a full summary of all the changes in the proposed HON.

The proposed changes to HON are the latest in a string of rulemakings that add more stringent requirements for sources in the petrochemical sector, starting with the refinery sector rule (RSR) in 2015. These regulations, including NESHAP affecting the ethylene production sector and the miscellaneous organic chemical manufacturing sector included similar requirements to those in the proposed HON revisions. In this article, we’ve summarized some lessons learned from helping petrochemical sector clients with these regulatory changes to ensure an easy road to compliance with the revised HON.

Lesson 1: Start Early

This may seem obvious, but it’s not too early to start evaluating how changes to HON may affect your facility. Once finalized, existing affected facilities could have as little as one year to comply with some provisions of the proposed rule while new affected facilities could have as little as 60 days to comply. Compliance dates are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Proposed Compliance Times for HON Provisions

| Requirement | Proposed compliance date for affected sources that… | |

| Commence construction or reconstruction on/before 4/25/2023 | Commence construction or reconstruction after 4/25/2023 | |

| Ethylene Oxide Provisions | 2 years after final rule is published or upon startup, whichever is later | 60 days after final rule is published or upon startup, whichever is later |

| Fenceline Monitoring | 1 year after final rule is published to begin monitoring 3 years after final rule is published to evaluate corrective actions |

|

| Other Provisions | 3 years after final rule is published or upon startup, whichever is later | |

Compliance with the proposed HON may require a capital project either to install a new control device to control process vents that currently vent to atmosphere or to upgrade a control device such as an existing flare to meet the increased monitoring requirements. Capital projects could require significant engineering, procurement of equipment with long lead times, construction permitting, and even a unit shutdown; therefore, these types of projects need to be planned far in advance to be considered in budgets and production schedules. Now is a great time to evaluate your affected sources to assess if any modifications are necessary to meet the proposed revisions to the HON.

Lesson 2: Consider a Pilot Study

Fenceline monitoring is a new requirement proposed to be added to the HON. While the RSR only required monitoring for benzene, HON facilities have an expanded list of chemicals that must be monitored depending on whether they are used, produced, stored, or emitted. Monitoring frequencies may also vary – for example, ethylene oxide and vinyl chloride have a 24-hour sampling period once every five days compared to other chemicals (such as benzene) which have a 14-day sampling period. Fenceline monitoring data collected by HON facilities will be reported to U.S. EPA quarterly and made available to the public.

Many HON facilities have not collected concentration data for these chemicals at their fencelines before. A pilot study is one effective tool to better understand these concentrations and benchmark performance relative to the proposed action levels. In addition, early data collection gives your facility time to implement potential corrective actions ahead of the effective date of the rule, improving compliance once the rule is in effect. Pilot studies also provide an opportunity to try siting monitors at different locations and to understand potential offsite impacts on a facility’s fenceline monitoring data. Facilities subject to the HON can submit Site Specific Monitoring Plans (SSMP) to the U.S. EPA for approval to account for these offsite impacts. ALL4’s Air Quality Modeling and Monitoring team has deployed fenceline monitoring systems and can help conduct a pilot study at your facility.

Lesson 3: Engage Stakeholders Across Your Facility

While the environmental department is typically responsible for implementing changes to comply with the revised HON, those personnel will need buy in from across the facility and the organization to be successful. For example, operations may need to make process vent determinations, process engineering may need to design a capital project, controls engineering may need to implement new flare monitoring, and procurement may need to secure new vendors such as a turnkey fenceline monitoring service or order equipment with long lead times. Engage these resources now by sharing information about the proposed rule changes so that key decision makers aren’t surprised when the HON is finalized and the clock is ticking to comply.

ALL4 has already begun assisting our clients with developing strategies on how to comply with the proposed HON while we await the final rule, which is expected in March 2024. If you’d like to talk about what you can do to get your facility ready for compliance, you can reach out to me at klingard@all4inc.com or (470) 231-3770 or contact your ALL4 project manager.

Advancing Environmental Justice: New Jersey’s Approach to Addressing Cumulative Stressors

Advancing Environmental Justice: New Jersey’s Approach to Addressing Cumulative Stressors

On April 17, 2023, the final Environmental Justice (EJ) Rule (N.J.A.C. 7:1C) officially became effective in New Jersey (NJ). The overall goal of this EJ Rule is to avoid disproportionate impact to overburdened communities (OBC) that could occur by a facility creating stressors or a facility contributing to a community already subject to stressors. While announcing the Nation’s first ever EJ Rule, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy stated, “…the final adoption of DEP’s EJ Rules will further the promise of environmental justice by prioritizing meaningful community engagement, reducing public health risks through the use of innovative pollution controls, and limiting adverse impacts that new pollution-generating facilities can have in already vulnerable communities” (NJDEP). Further general applicability of New Jersey’s EJ Rule can be referenced here.

What are the Environmental and Public Health Stressors of NJ’s EJ Rule?

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) analyzed various factors that impact OBCs and identified 26 stressors that are considered in the EJ Rule. The environmental or public health stressors are either a source of environmental pollution or a source that may cause public health impacts. NJDEP selected these stressors by choosing at least on core stressor in each of the legislatively mandated categories of concern, the quantifiability of the stressor, the availability of meaningful data in at a geographic scale, the value of the stressor in terms of representing the concern in an OBC, and consistency with stressors chosen by California or EPA. The 26 stressors are listed in the table below along with their brief description.

The Environmental and Public Health Stressors of New Jersey’s EJ Rule

| # | Stressor | Description |

| Concentrated Areas of Air Pollution | ||

| 1 | Ground-Level Ozone | Days above National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) |

| 2 | Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) | Days above NAAQS |

| 3 | Cancer Risk from Diesel Particulate Matter (PM) | Estimated cancer risk |

| 4 | Cancer Risk from Air Toxics Excluding Diesel PM | Estimated cancer risk |

| 5 | Non-Cancer Risk from Air Toxics | Estimated noncancer risk |

| 6 | Permitted Air Sites | Number of sites per square mile |

| Mobile Sources of Air Pollution | ||

| 7 | Traffic – Cars, Light- and Medium-Duty Trucks | Vehicle density per square mile |

| 8 | Traffic – Heavy-Duty Trucks | Vehicle density per square mile |

| 9 | Railways | Rail miles per square mile |

| Point Sources of Water Pollution | ||

| 10 | Surface Water | Non-attainment of designated uses for the Integrated Report |

| 11 | Combined Sewer Overflows | Number of CSOs in block group |

| 12 | NJPDES Sites | Number of sites per square mile |

| Solid Waste & Scrap Yards | ||

| 13 | Solid Waste Facilities | Number of transfer stations, solid waste and recycling facilities, and incinerators per square mile |

| 14 | Scrap Metal Facilities | Number of sites per square mile |

| Contaminated Sites | ||

| 15 | Known Contaminated Sites | Density of Weighted Known Contaminated Sites (KCSL) |

| 16 | Soil Contamination Deed Restrictions | Percent acres of the block group with Deed Notice restrictions |

| 17 | Groundwater Classification Exception Areas/Current Known Extent Restrictions | Percent acres of the block group with Classification Exception Area (CEA) or Currently Known Extent (CKE) notice restrictions |

| May Cause Public Health Issues: Environmental | ||

| 18 | Drinking Water | Number of Maximum Concentration Level (MCL), Treatment Technique (TT), and Action Level Exceedance (ALE) violations |

| 19 | Emergency Planning Sites | Density of TCPA, DPCC and CRTK facilities |

| 20 | Potential Lead Exposure | Percent of pre-1950 housing |

| 21 | Lack of Recreational Open Space | Population living greater than a ten-minute walk (1/4 mile) from Public Recreational Open Space |

| 22 | Lack of Tree Canopy | Spatially weighted mean tree canopy cover |

| 23 | Impervious Cover | Percent impervious surface in a block group |

| 24 | Flooring (Urban Land Cover) | Percent of urban land use area flooded |

| May Cause Public Health Issues: Social | ||

| 25 | Unemployment | Percent of an adult population that is unemployed |

| 26 | Education | Percent of an older population that has less than a high school diploma |

Initial Screening

Once a facility subject to the EJ Rule submits a permit application, the NJDEP completes an initial screening of the facility and the surrounding community. The goal of the initial screening is for the facility to work with the NJDEP to confirm the facility is in an OBC and identify which stressors are being impacted by the facility and which stressors are already borne by the OBC. The following information will be provided to the facility via the initial screen:

- Identification of the environmental and public health stressors that are impacted by the facility.

- The geographic point of comparison.

- Chosen non-OBC location in New Jersey in which the stressors are compared to.

- Identification of environmental and public health stressors that are higher than 50th

- The Combined Stressor Total (CST) of the OBC.

- This is the total count of stressors in an OBC that are higher than the geographical comparison result.

- Identification if the OBC is subject to adverse cumulative stressors.

- Adverse cumulative stressors exist when the sum of CSTs of a community is higher than the geographic point of comparison.

Environmental Justice Impact Statement

After meeting with NJDEP and agreeing on the facility’s initial screening, the next step is to complete the Environmental Justice Impact Statement (EJIS). If it is determined in the initial screen that the OBC is not subject to adverse cumulative stressors or the facility can demonstrate avoidance of disproportionate impact, then the facility is only subject to completing an EJIS. If it is determined in the initial screen that an OBC is already subject to cumulative stressors or the facility cannot demonstrate disproportionate impact avoidance, the facility is required to complete an EJIS and provide supplemental information.

Preparing an EJIS is an extensive, meticulous process. The following information should be provided in an EJIS deliverable:

- An executive summary including supplemental information, if applicable.

- A description of the facility location with a site plan or map.

- A description of the facility’s current/proposed operations.

- Provide a list of all required Federal, State, and local permits for construction and operation.

- Evidence of satisfaction of any local EJ or cumulative impact analysis ordinances.

- The initial screening obtained from NJDEP.

- Assessment of both positive and negative impacts of the facility on each environmental and public health stressor in the OBC.

- A public participation plan with all proposed forms and public notice information.

- Proof the facility will avoid disproportionate impact.

- A brand-new facility must provide how they will serve a compelling public interest in the OBC.

Meaningful Public Participation

Upon submitting an EJIS, the facility must conduct a public hearing in the OBC to present the EJIS. Public notices must be published in multiple forms which include newspaper publications, notifications to property owners within 200 feet of the facility, online publications and post a sign at the facility location. There is a required minimum 60-day public comment period, and the facility must respond to all comments in writing. After this, the NJDEP will review the application, initial screening, EJIS, and public comments for a minimum of 45 days and determine if the facility can avoid a disproportionate impact to the OBC. It is important to note that the public participation period alone is a minimum of 105 days. If possible, the NJDEP will impose permit conditions necessary to ensure no impact will occur. If it is determined that avoiding disproportionate impact to the OBC is not possible, then the permit application will be denied unless there is compelling public interest from the OBC, or permit renewals will be subject to appropriate conditions to address facility impacts. Listed below is a summary of possible permit conditions:

- Permit Renewals

- Avoid OBC impacts but if not avoidable, then minimize impacts as much as possible.

- Permits for New and Expanded Facilities

- Consider additional conditions to reduce off-site stressors and/or provide a new environmental benefit that will improve overall environmental and public health stressors.

- Localized Impact Control Technology

- Standards for major source components based on existing air program standards will address sites impacted by lack of technology upgrades. To reduce pollution the focus will be on technological feasibility.

If you have questions or need assistance planning for compliance with the NJDEP EJ Rule, please contact Lillia Blasius at lblasius@all4inc.com or (770) 999-0270. ALL4 also has additional resources available online, including a blog about the general NJDEP EJ Rule applicability, New Jersey Environmental Justice Final Rule Effective April 17, 2023, and our original coverage of the Rule, NJDEP Proposes Environmental Justice Rule.

How the U.S. EPA’s New Methylene Chloride Regulations May Affect You.

Methylene chloride (MC), a chemical commonly used as a solvent for surface refinishing and in the production of pharmaceuticals and refrigerants, is set to be banned by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) for most uses. Products containing MC are set to be unavailable for all consumer uses and most industrial/commercial uses at some point in the year 2024.

What is Happening?

In 2016 congress amended the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) which gave U.S. EPA the authority to assess and address risks associated with chemicals that are considered dangerous. Under TSCA, U.S. EPA identified 10 chemicals of interest that have been subject to U.S EPA’s new evaluations. The second chemical to be evaluated and have new regulations proposed was MC. After this evaluation U.S. EPA determined that MC posed an “unreasonable risk” to the consumer and began writing a regulation to prohibit consumer use in every circumstance and prohibit manufacturing of MC in almost all scenarios. The regulatory development to control MC first began in 2019, when U.S. EPA utilized TSCA to prohibit the manufacturing of paint and coating removers containing MC based on data showing it had caused an unreasonable number of fatalities from improper use. Following this development, U.S. EPA continued their investigation and in May 2023 determined that the “unreasonable risk” it posed warranted a complete consumer ban and severe restrictions to manufacturing and industrial/commercial use. The commenting period has ended, and U.S. EPA is looking to finalize the regulation and have the first prohibitions in place sometime in 2024. U.S. EPA has proposed that a cease of production for consumer and commercial uses be implemented within 90 days of issuance of the final rule and retail sales stopped within twelve months.

What industries are affected by this proposed regulation?

Although the regulation prohibits most industrial and commercial use of MC, there are certain industries and uses that will continue with application of U.S. EPA’s Workplace Chemical Protection Program (WCPP). Manufacturing that incorporates MC into a mixture or uses it as a processing aid or is engaged in coating or cleaning corrosion-sensitive components of aircraft or spacecraft owned by the Department of Defense (DOD), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), or the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) must implement a WCPP. U.S. EPA is allowing specific exemptions under TSCA Section 6(g) to not significantly disrupt national economy, security, or critical infrastructure. In these cases, MC can still be produced or used after receiving approval from U.S. EPA and ensuring they implement a WCPP. However, industry advocates who have read the WCPP requirements believe that it has gone too far and is too stringent in the handling of MC.

How has industry opposed this regulation?

Opponents of this regulation believe it is overreaching and is too restrictive in the limited allowed uses and the significant tightening of worker exposure levels. U.S. EPA has expressed that although there may be an economic impact to both industries and consumers, the main priority of this regulation is the protection of the health and safety of workers and consumers. Some argue that the WCPP set by U.S. EPA are excessive, citing the permissible exposure limits proposed in the regulation are ten times lower than the limits currently in place by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). U.S. EPA has cited that these regulations fall in line with more up to date safety and exposure guidelines that reflect the dangerous nature of MC. In addition to lowering the exposure limit for workers the rule also includes stringent monitoring, recordkeeping, and dermal requirements.

What are your next steps?

Despite the outcry, U.S. EPA’s TSCA regulation of methylene chloride will be enforced in the near future. Understanding if you or your company will be affected by U.S. EPA’s ban is the first step towards meeting compliance. If you are exempt from this ruling ALL4 can assist you with implementing your workplace chemical protection program, and from there assist you in implementing the proper steps to fully meet regulatory compliance. If you are interested in learning more about how you can comply, please feel free to contact Peter Chetkowski at pchetkowski@all4inc.com or at 502-493-6448.