New Jersey CEMS Quality Assurance Requirements for Non-Operating Quarters

On May 21, 2019, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) Emission Measurement Section (EMS) issued clarifications to Technical Manual #1005 (TM1005). These clarifications were sent out via email through the EMS Listserv and are intended to provide clarification to the quality assurance (QA) requirements for continuous emissions monitoring systems (CEMS) during non-operational quarters. The archived message is available for review on NJDEP’s website.

TM1005 includes NJDEP guidelines for monitoring (i.e., continuous and periodic) and annual combustion adjustments. Section VI(I) of TM1005 requires that CEMS, required by permit to demonstrate compliance with allowable emissions, be quality assured in accordance with 40 CFR Part 60, Appendix F. Further, 40 CFR Part 60, Appendix F, Procedure 1 (Procedure 1) requires that either a quarterly cylinder gas audit (CGA) or relative accuracy test audit (RATA) be completed in each quarter that the source operates. §5.1.4 of Procedure 1 then goes on to state that a CGA or RATA is not required in a quarter where the source does not operate, with the caveat that if a RATA is required during the non-operational quarter it is then due in the quarter which the source recommences operation. Note that while Section VI(I) of TM1005 also allows a CGA to be conducted in lieu of a linearity test when a required linearity test is not performed due to the Part 75 grace period. That situation is not addressed by this article because the Part 75 grace period only comes into play in quarters where some operation took place.

It is the opinion of NJDEP EMS that the QA exemptions were not intended for continued periods of non-operation. The purpose of the May 21, 2019 email is to provide affected facilities with clarification regarding QA requirements during instances of multiple successive non-operational quarters when there is a break in quarterly QA activities. The following scenarios are presented to identify, and simplify, what QA activities are required relative to the source’s operational status.

- First Non-Operational Quarter: In accordance with Procedure 1, if a CGA or RATA is required in the first quarter of non-operation, the facility may opt to skip the required quarterly test.

- Second Consecutive Non-Operational Quarter: If a CGA was required in the first non-operational quarter, a CGA must be completed in this quarter regardless of the operational status of the source. If a RATA is required in the second consecutive non-operational quarter, the facility must perform a CGA while the source is not operating. A common term used to denote a CGA performed while the source in not operating is an off-line CGA. This term will be used for the remainder of the article to identify this QA scenarios.

- Subsequent Non-Operational Quarters: Facilities have the option to discontinue quarterly QA tests if a source will be non-operational for an extended period of time (i.e., exceeding two consecutive non-operational quarters). However, in certain situations it makes sense to continue with the quarterly QA testing regardless of the operational status of the source. If a facility opts to continue quarterly QA, then an off-line CGA test is required in each non-operational quarter. It is important to note that the following caveats also apply when it comes to extended periods of non-operation.

- If the facility chooses to discontinue quarterly QA for two or more consecutive quarters, a Performance Specification Test (PST), performed in accordance with the procedures outlined in either Option 1 or Option 2 of Appendix E of TM1005, will be required the quarter in which the source resumes operation.

- If the unit is non-operational for five or more consecutive quarters, and one of those quarters includes a quarter without QA, it is considered a recertification event and a PST must be performed the quarter in which the source resumes operation.

- If the facility chooses to continue quarterly QA during non-operating quarters, it can be done by performing an off-line CGA in each quarter including the quarter in which the RATA was due. However, if the facility goes six or more quarters without performing a RATA, a PST is required to be completed the quarter in which the source resumes operation.

- Source Resumes Operation: If a CGA is due the quarter in which the source resumes operation, the CGA is required upon startup. If a RATA is due when the source resumes operation, the facility must follow the procedures detailed in Option 1 of Appendix E to TM1005. When following Option 1 for this purpose, substitute RATA for PST and exclude references to 7-day drift assessments. Alternatively, the facility may also choose to conduct a full PST as described in Option 2 of Appendix E to TM1005.

Now that we have discussed the required quarterly QA tests based on the length of the non-operational period, it is important to address data validation in relation to the performance of these tests. TM1005 requires valid data reporting upon start-up, unless the facility has a Start-up Operating Scenario that allows for something different. So, what does this mean to you? It means that a source required to perform a CGA, either as a standalone test, or as part of a PST performed in accordance with Option 1 of Appendix E to TM1005, must report downtime for operational periods from the time the source resumes operation to the completion of the CGA. For facilities electing to perform a full PST in accordance with Option 2 of Appendix E to TM1005, data is considered invalid from the time the source resumes operation until the completion of the calibration drift check on day 1 of the 7-day calibration drift period. It is important to note that if a PST is required (following either Option 1 or Option 2) the above information assumes that the RATA is passed. If the RATA is not passed, then the data from the time that the source resumed operation until the completion of a successful RATA will be considered invalid and is required to be reported as downtime.

This article focuses on the quarterly quality assurance requirements, and the associated data validation, during extended periods of unit non-operation. However, it is also important to mention that affected facilities should update their CEMS Quality Assurance Plan (QA Plan) to reflect the NJDEP update. If you have questions about the content of this article or would like assistance with updating your QA Plan, please feel free to contact me. I can be reached at 610.422.1164 or at jmillard@all4inc.com.

What is the U.S. EPA Air Office Working on These Days?

Update: On June 26, 2019, U.S. EPA Assistant Administrator Bill Wehrum has stepped down from his role in the Office of Air and Radiation. The regulated community may see delays in rulemaking until a permanent replacement is named. Please check ALL4’s website for regular updates.

In the early days of the current U.S. EPA administration, we began hearing that U.S. EPA was going to reform the New Source Review (NSR) air construction permitting process. U.S. EPA gathered thousands of comments on how to streamline the air construction permitting process and what their air regulatory reform priorities should be. These priorities, particularly around NSR permitting, were widely anticipated because the NSR permitting process impacts the most strategic, capital intensive, and time sensitive projects that facilities undertake. We heard promises of small NSR changes via memo, guidance, and rulemakings that would come out at a frequency of one per month. The assistant administrator for the U.S. EPA Office of air and Radiation, Bill Wehrum, used a baseball analogy to promise a series of “singles and doubles” but no home runs. In other words, small-scale changes that could be implemented quickly rather than sweeping reforms that would take years to complete.

For a while we did see actions about once per month, including projected actual emissions, project emissions accounting, source reactivation, and a few items related to aggregation. The following NSR highlights occurred in 2018:

- Ten items were added to U.S. EPA’s NSR Policy and Guidance Document Index,

- U.S. EPA finalized the 2010 project aggregation reconsideration action,

- U.S. EPA released a draft guidance document that proposed a small revision to its ambient air policy for comment, and

- U.S. EPA released a draft guidance on adjacency for comment.

However, in 2019 we seem to be in a rain delay in terms of permitting reform actions. We are waiting on the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to finish its review of a proposed project emissions accounting rulemaking and a rulemaking to repeal the once-in always-in MACT policy, and we are waiting on U.S. EPA to release final ambient air and adjacency guidance memos. Those items may be the only further permitting-related actions we see until the fall of 2019.

Why the rain delay? U.S. EPA is likely learning from environmental groups’ legal pushback to previous policy changes (e.g., the legal challenge to the project emissions accounting guidance) and taking their time to think through the appropriate mechanisms to effect change and also to bolster the record supporting their reforms. There have been some leadership changes within the agency that may have slowed progress or re-ordered priorities. Finally, U.S. EPA has realized that for some actions they would like to take, rulemaking is preferable to guidance. Although a rulemaking action takes longer to complete than issuance of a guidance document, it results in more consistent implementation across state and local agencies.

What NSR reform related actions are we likely to see next? U.S. EPA has indicated to multiple audiences that the next items we should see are: guidance on “begin actual construction” (e.g., to allow additional site preparation activities prior to issuance of a PSD permit); guidance related to routine maintenance, repair, and replacement (such as clarification that routine means routine within the industry, not just at the plant or within a company); guidance on Plantwide Applicability Limits (PALs) (anticipated to include language to lessen the chance of an agency automatically reducing PAL levels closer to recent actual emission levels upon renewal of the PAL); and guidance on properly estimating demand growth associated emissions and emissions that could have been accommodated during the baseline period for PSD applicability. It could be football season before we see these next NSR reform items.

What else is U.S. EPA working on? They are hard at work on 26 Maximum Achievable Control Technology (MACT) risk and technology review (RTR) rules that are under a court ordered deadline to go final in 2020, and another 9 that must be finalized in 2021. This year we will see quite a few RTR rule proposals that will impact the chemical industry, such as the organic liquids distribution (OLD) MACT, the Miscellaneous Organic National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants [(NESHAP) MON], the Ethylene MACT, and Miscellaneous Coatings Manufacturing. We can anticipate several changes to these rules based on the recent work U.S. EPA did to revise the Refinery MACT (e.g., for flares, pressure relief devices, leaks, and startup/shutdown), but there will also be some tightening of requirements for processes in ethylene oxide (EO) service, due to heightened concern about risk from emissions of that compound. U.S. EPA has established a website dedicated to providing the latest information on its work to address risk from EO emissions, and has committed to re-examining the RTR for ethylene oxide sterilizers that it completed in 2006 prior to the revision of the risk factor for EO. We also know from the most recent regulatory agenda that U.S. EPA is also working on several other items, such as a reconsideration of the polyvinyl chloride (PVC) MACT rule, revisions to the Boiler MACT rule (based on the outcome of litigation), and several National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)-related obligations. The World Series will likely have been decided before we see some of these items.

It could be that all the other regulatory items that U.S. EPA must complete for upper management approval are contributing to the NSR reform rain delay. Although we may be in an early-summer lull, rest assured, there will be plenty of reading to do during the second half of the year. For updates, you can contact Amy Marshall at 984-777-3073 or amarshall@all4inc.com or Colin McCall at 678-460-0324 x206 or cmccall@all4inc.com.

A Message to Our Clients – Growth at ALL4…

“Growth” is a word that has been used A LOT here at ALL4 recently. Whether it is growth in the number of consultants, or new offices (check out our new Raleigh Office Announcement), or new leadership and technical opportunities for our team, growth is a central theme internally at ALL4. But growth at ALL4 also benefits our clients.

First, we continue to expand our geographic footprint so that we can support our clients through a local presence. We have served our clients through a centralized strategy across the country and we have also served them through a localized and more tightly connected strategy. While both approaches have worked, we will continue to expand our footprint to add top quality consulting talent and to build a network of locations that meet our clients’ needs. Beyond the obvious advantages of proximity to clients, geographic expansion also allows us to become further connected with state regulatory agencies for the benefit of our clients.

Second, we continue to grow and expand our air quality expertise. We are adding new talent to supplement our existing core service areas of: air quality permitting, air quality compliance, ambient pollutant and meteorological monitoring, air quality modeling, continuous monitoring systems, environmental program management, and multimedia regulatory analysis. Simultaneously, we are looking to expand our core air service areas so that clients see ALL4 as the “one stop shop” for air services.

Finally, we seek to make it known that our environmental services go beyond air! Traditional community right-to-know reporting, spill prevention and countermeasure control (SPCC) plans, water and waste water permitting, environmental audits, environmental training, and environmental due diligence are services that we have been providing and will continue to expand upon. As we add top quality consultants, they often have expertise that reach beyond our traditional core services that is available for the benefit of our clients! If you have a need beyond air… ask us! Our commitment is this – we will be honest with our capabilities and we will help you find the right solution if we believe that we are not the best fit.

We believe that growth at ALL4 is great for our team AND great for our clients. With that in mind, expect ALL4 consultants to share new capabilities with you, our clients. If you have an environmental area where you feel underserved, let us know! As we continue to grow, we will do so in a way that increases our connection with your environmental teams and maintains the same level of quality and strategic thinking that you have come to expect from ALL4.

I encourage you to talk to your ALL4 Manager directly about additional services, and if you are new to ALL4, please contact us to discuss how we can help your facility.

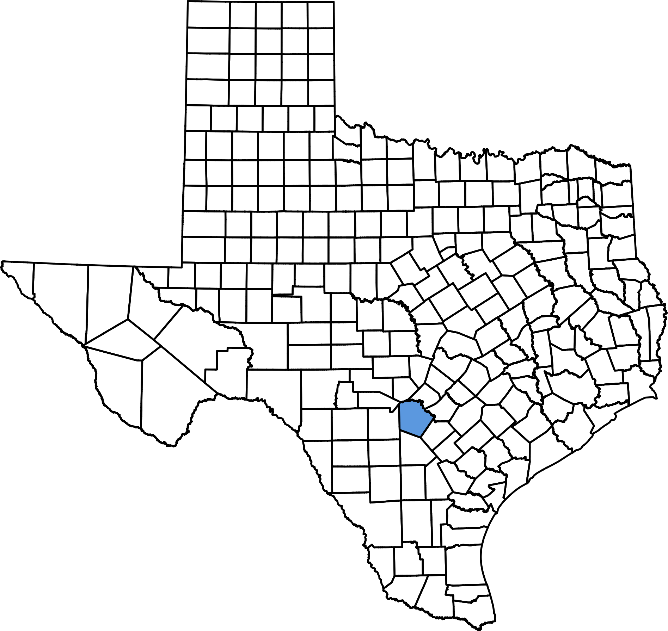

Texas SIP Emission Inventory Revisions for Sites in Bexar County

In case you have not been following, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) designated Bexar County (San Antonio area) as nonattainment for the 2015 eight-hour ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS). This designation was effective on September 24, 2018. Sources located in nonattainment areas must have SIP emissions in order to generate and create emission reduction credits (ERC). SIP emissions represent the actual emissions from a given facility in a designated nonattainment area during the state implementation plan (SIP) emissions year. SIP emissions cannot exceed applicable state, local, or federal requirements. Therefore, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) is preparing an emission inventory (EI) state implementation plan (SIP) revision for three ozone nonattainment areas, including Bexar County. The SIP emissions year for Bexar County will be 2017. Because Bexar County has been newly designated as nonattainment, TCEQ is allowing facilities in Bexar County to review reported 2017 emissions data and to submit valid revisions to their 2017 calendar year EIs. Revisions to the 2017 EIs are required to be submitted to TCEQ no later than July 31, 2019 and must be certified and submitted via hardcopy paper forms. Once TCEQ approves the received information, the EI SIP revision will be adopted for emissions credit generation.

Why is This Important?

The air quality permitting implications for major stationary sources of the ozone precursors nitrogen oxides (NOX) and volatile organic compounds (VOC) located in ozone nonattainment areas can be daunting. Under certain circumstances, ERCs are required as emissions offsets to facilitate facility changes that are major modifications under the TCEQ nonattainment new source review (NNSR) regulations. ERCs can be generated by over-controlling actual emissions or by reducing actual emissions though shutdown or limitations on operations and emissions. ERCs must be surplus, permanent, quantifiable, and federally enforceable. ERCs can be sold to other facilities located within the same nonattainment area if not needed at the facility where they originated. Because ERCs are based on reported emissions, it is important that emissions reported by facilities be as accurate as possible.

Things to Keep In Mind

The request from TCEQ only applies to valid revisions for the 2017 emissions year and does not represent an opportunity for amnesty for emissions inventories that may have been required at the time but were not submitted. The sites that would have submitted EIs for the 2017 emissions would have either been a major source or would have been notified by a TCEQ special inventory request. As mentioned above, the revised EIs are required to be submitted hardcopy and are NOT to be submitted through the State of Texas Environmental Electronic Reporting System (STEERS). Documentation, such as sample calculations, appropriate signatures, etc. are also required. If revisions contain confidential information, the site is responsible for designating that information as such.

What is Next?

This is an opportunity for facilities in Bexar County to double check and revise, as appropriate, reported emissions for 2017. Reported 2017 emissions could be the basis to generate valuable ERCs. It is therefore important that a site review its 2017 EI to confirm its accuracy, especially if emissions were inadvertently under reported. If a 2017 EI revision is submitted, the site must also be aware of other reports or documents that may be impacted as a result of the revisions. For example, the air emissions fees would differ and may also need to be revisited. Because TCEQ has allowed this opportunity to reexamine 2017 EI data, it is certainly worth-while for facilities in Bexar County to take another look at their previously submitted data before the deadline.

Need Help?

If you need assistance reviewing or submitting revisions to your 2017 EI, feel free to reach out to me, Frank Dougherty at fdougherty@all4inc.com, 281-937-7553 x302.

Photo Credit:

https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/texas/bexar-county

Georgia Permittees (Major, Minor, and Synthetic Minor): Permit Application Fees are in Effect

Last year ALL4 published a blog post covering the proposed amendments to Georgia Administrative Code (G.A.C.) 391-3-1-.03(9), which addressed Georgia’s proposed air permit application fees. The permit application fees were adopted into rule in April 2018 and officially went into effect on March 1, 2019. Now that the permit application fees are in effect, here are five important things that facilities should be aware of.

- Permit application fees vary by permit type.

Permit application fees range from $0 up to $7,500 depending on the type of permit application. The Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GEPD) has published a list of all permit application types and associated fees on the Air Permit Fees website and within the most recent Air Permit Fee Manual (For Fees Due Between July 1, 2019 and June 30, 2020). In addition, Section 2.3 of the Air Permit Fee Manual characterizes each type of permit application and associated permit application fee.

- The applicant is responsible for determining the applicable fee(s).

Using Section 2.3 of the Air Permit Fee Manual, the applicant is expected to determine the applicable permit application fee(s) for each permit application. In the case where a permit application falls under multiple permit types, the applicant is expected to pay the greater of the fees.

- Payment is due within 20 days of permit application acknowledgement.

Following submittal of a permit application, a staff member of the GEPD Air Protection Branch should provide the applicant with acknowledgement that the permit application has been received. The applicant must submit the permit application fee payment within 20 days of the acknowledgement.

- Invoices are generated via the Georgia Environmental Connections Online (GECO) system.

Permit application fee invoices are generated via the GECO system, similar to how annual emissions fees invoices are generated. The preferred payment method for permit application fees is by check and all permit application fees are non-refundable.

- How do permit application fees factor into project planning?

Facilities will now need to factor the cost of permit applications into overall project budgets and annual facility planning. Knowing whether a project will require a Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) or Title V Significant Modification with Construction permit application at the outset of the project will be important for facility planning purposes. The difference in these permit application fees alone can differ by $5,500.

If you have any questions concerning Georgia’s new permit application fees, please reach out to me at 678.460.0324 x213 or sarner@all4inc.com. Thanks for reading!

The Ever-Evolving Science of Air Quality Modeling

One of the reasons I’ve enjoyed air quality modeling during my 16-year career with ALL4 is because it’s an ever-evolving science. The air quality modeling that I was learning and conducting 16 years ago is vastly different than the air quality modeling associated with my current and future modeling projects. This seems to marry well with what I believe was the most important lesson I learned in college. That is, I learned how to learn. This has been critical to me in learning the evolving science and the associated regulations related to air quality modeling.

Learn More About Air Quality Modeling

By design, the framework that governs air quality modeling, 40 CFR Part 51 Appendix W – Guideline on Air Quality Models (The Guideline) is setup to incorporate the current state-of-the-science. This was evident from the beginning with the 1977 Clean Air Act (CAA) that legislated a requirement [42 U.S.C §7620(a)] to conduct a conference on air quality modeling “Not later than six months after August 7, 1977, and at least every three years thereafter.” The purpose of the triennial “Conference on Air Quality Models,” as it has come to be known, is to provide an opportunity for State and Local air pollution agencies, scientific bodies, and the regulated community to participate and contribute to the current state-of-the-science as it relates to air quality modeling. I’ve had the opportunity to participate and attend the 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th U.S. EPA hosted Conference on Air Quality Models. A parallel technical program for air quality modelers has been organized by the Air and Waste Management Association (AWMA). AWMA has hosted several air quality modeling specific conferences and in March 2019 I attended one such conference titled the “Guideline on Air Quality Models: Planning Ahead.” U.S. EPA also attended the March 2019 AWMA conference and tentatively scheduled the 12th U.S. EPA Conference on Air Quality Models for October 1-3, 2019 in Research Triangle Park, NC.

The AWMA conference was a great venue to hear about the current state-of-the-science and what other consultants and scientific bodies are currently working on. It was also a great venue to hear from the U.S. EPA Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards (OAQPS) Air Quality Modeling group about their priorities and future plans. The rest of this article summarizes some of the key updates from the AWMA conference and other recent actions with a focus on how it might affect your next project that involves air quality modeling.

Revised Policy on Ambient Air

U.S. EPA provided background about items addressed in the November 2018 draft “Revised Policy on Exclusion from Ambient Air” (Ambient Air Policy). Many in the regulated community didn’t think the policy went far enough in redefining “ambient air” (i.e., the area where the general public can be exposed to air pollutants) because it didn’t address the duration component associated with ambient air for individual pollutants. Specifically, some National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) have only long-term averaging periods (i.e., 24-hour or annual) and the period of exposure should have been addressed for locations where it would be highly improbable for the public to reside for long term durations. U.S. EPA’s response was that the items addressed in the Revised Ambient Air Policy were as far as they could go without rulemaking and based on previous experience without risking significant legal challenges. The takeaway for your next project is that the revised Ambient Air Policy replaces “a fence or other physical barriers,” with; “Measures, which may include physical barriers, that are effective in deterring or precluding access to the land by the general public.” The Revised Ambient Air Policy identified “measures” as:

- Video surveillance and monitoring

- Clear signage

- Routine security patrols

- Drones

- Potential future technologies

While some facilities may already rely on these measures, the policy provides a backstop if your next project were to get challenged, provides consistency across state and U.S. EPA regions, and may provide consistency between Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) permitting and State rule air quality modeling.

Update on Modeled Emissions Rates for Precursors (MERPs)

During the AWMA conference U.S. EPA gave a preview to updates to be incorporated into a final version of the “Guidance on the Development of Modeled Emissions Rates for Precursors (MERPs) as a Tier 1 Demonstration Tool for Ozone and PM2.5 under the PSD Permitting Program” and also indicated that the final version would be published by the end of April 2019. Low and behold, U.S. EPA kept their word and released the final version of the guidance on April 30, 2019. If MERP is a new acronym to you check out ALL4’s blog post on MERPs when the draft guidance was published in December 2016.

As a quick refresher, MERPs are essentially emissions thresholds that can be utilized as part of a PSD permit to demonstrate that proposed increases in fine particulate (PM2.5) precursor emissions [sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOX)] and ozone precursor emissions [volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and NOX] from your project will be below ozone and PM2.5 significant impact levels (SILs) and therefore won’t have the potential to cause or contribute to a violation of the NAAQS. The MERPs are based on photochemical modeling conducted across the U.S. and are regionally representative.

A MERP analysis is considered a Tier I demonstration and if your project-related precursor emissions are greater than the MERPs, a Tier II demonstration would be required involving the use of a photochemical grid model. However, before you get too worried about conducting photochemical modeling, I was also interested to hear, that since the draft 2016 MERP guidance has been released there have been no submitted permit applications utilizing a Tier II demonstration and that all applications triggering the requirement to evaluate precursor impacts have successfully relied on a Tier I demonstration.

Changes from the 2016 draft guidance to the April 30, 2019 final version included:

- Additional hypothetical single source modeled sources,

- Additional details on how to use existing modeling for NAAQS demonstration, and

- Additional details on considering secondary PM2.5 for PM2.5 PSD increment demonstrations.

The changes related to the additional hypothetical single sources are good news for those projects that may require further refinement from use of the most conservative illustrative MERPs which are geographically categorized by eastern, central, and western regions. Specifically, more geographically and stack height specific MERPs can be developed for your facility. It appears that the approach of developing a more geographically and stack height site-specific MERP value is what has enabled everyone to avoid a Tier II demonstration to date. The Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GA EPD) Air Quality Division seems to be leading the way with state-specific guidance that outlines how to develop refined MERP values. In addition, GA EPD has even conducted additional photochemical modeling to add their own state-specific facilities. The Kentucky Department of Environmental Protection (KYDEP) and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) have also developed similar MERP guidance on refining MERP values for your site.

Clarification on Local Source Emissions Rates used for NAAQS Modeling Demonstrations

During the AWMA townhall event, U.S. EPA representatives sought to provide clarity on a misinterpretation many may have been making with respect to the 2017 Guideline amendments. The potential misinterpretation centers around amendments made to 40 CFR Part 51 Appendix W Section 8.2.2 Table 8-2 that summarizes the modeled emissions inputs for NAAQS compliance demonstrations as part of PSD permits. Specifically, the 2017 amendments updated language to allow use of average actual emissions for nearby sources when adjusting for the operating level. This adjustment has been misinterpreted by many in the regulated community to be synonymous with modeling actual reported emissions from the most recent two years when modeling local sources as part of a NAAQS compliance demonstration. However, the slight nuance is that the two most recent years of actual emissions can be used to develop an operating level [i.e., Million British thermal units (MMBtu)/hr or lb throughput/hr] that can be multiplied by the maximum allowable emissions limit or federally enforceable permit limit (i.e., lb/MMBtu or lb/throughput) to determine the required emissions rate. In some cases, this actual operating level emissions rate may be the same as the actual reported emissions but not in all cases. Adding to the confusion is that some State modeling requirements do allow the use of actual emissions when modeling local sources as part of state modeling requirements (not PSD modeling).

While it appears that some State agencies have been misinterpreting this slight nuance for PSD permitting, I suggest taking a closer look at it during your next project as it may leave your project vulnerable to increased scrutiny during the public review process. This particular clarification to NAAQS air quality modeling guidance was developed to provide for a more refined approach for addressing local sources, and while it still does, it may not be as “refined” as some would have liked.

Update on the 12th Conference On Air Quality Models

During the AWMA conference, U.S. EPA representatives gave a preview of the focus for their 12th Conference on Air Quality Models. U.S. EPA indicated that the recent conferences were structured to establish the even-numbered conferences (i.e., the 8th, 10th, and 12th conferences) as planning and development conferences and the odd-numbered conferences as official rulemaking conferences, also acting as the official public hearing for Guideline rulemaking. Therefore, the 12th conference will follow this format, and the priority will be on planning and development for potential rulemaking at the 13th conference. The planning and development conferences allow for more public involvement as they do not include official public hearings. In advance of the October 2019 conference, expect stakeholder groups (and me) to be asking what air quality modeling issues are important for your facility and need to be addressed.

U.S. EPA also outlined several AERMOD alpha options that they hoped to release before the conference so that the regulated community has a chance to evaluate and provide feedback during the conference. An alpha option within AERMOD is an option that is experimental and not for regulatory use. Once proper evaluation and peer review (as specifically defined in Section 3.2 of the Guideline) has been completed U.S. EPA can “graduate” the option to a beta option. A beta option can then be used for regulatory applications with an alternative model approval (also specifically defined in Section 3.2 of the Guideline). Rulemaking is then necessary to “graduate” from an AERMOD beta option to an AERMOD default option. The alpha options that stakeholders and U.S. EPA are working on address issues related to:

- Building Downwash,

- Low Wind Conditions,

- Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) Enhancement,

- Mobile Sources,

- Overwater Modeling, and

- Saturated Plumes/Plume Rise.

If you’re currently dealing with a project that involves air quality modeling and are having issues with any of these topics, reach out to me at (610) 422-1118 or at ddix@all4inc.com to learn more about how these options might help. There may be the opportunity to work together to move the science forward so that we can help some of these alpha options graduate to beta and default options for use in your next project.