PFAS: State-by-State Regulatory Update (July 2022 Revision)

Given the current lack of all-encompassing federal environmental regulation around per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), states are taking it upon themselves to set their own standards amid growing public scrutiny. With proposed house bills, rejections of bills, and other PFAS news popping up seemingly every day, it can be difficult to keep track of the regulatory climate and obligations. ALL4 is here to help.

Note: This information is current as of July 28, 2022.

First to level-set, several key PFAS regulations currently at the federal level are presented below in Table 1.

Table 1

|

||

| Category | Subcategory | Regulation |

| Water | Drinking Water

|

Health Advisory Level (HAL) of 0.004 parts per trillion (ppt) for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), 0.02 ppt for perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), 10 ppt for hexafluoropropylene oxide (HFPO) dimer acid and its ammonium salt (together referred to as ‘‘GenX chemicals’’), and 2,000 ppt for perfluorobutane sulfonic acid and its related compound potassium perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS).

Note: HALs are not enforceable. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) is moving forward to implement enforceable drinking water maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for PFOA and PFOS. U.S. EPA is also evaluating additional PFAS beyond PFOA and PFOS and considering actions to address groups of PFAS. The proposed MCLs are anticipated in Fall 2022, but an enforceable limit does not exist at this time. |

| Published the final fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) which will require sample collection for 29 PFAS between 2023 and 2025. | ||

| National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) | U.S. EPA issued a memo to agency water program directors which details how the U.S. EPA will address PFAS discharges in EPA-issued NPDES permits and provides recommended PFAS-related permit language. | |

| Air | N/A | There are no proposed or promulgated standards at this time. |

| Other | Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) | Section 7321 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (NDAA), which was passed in December 2019, immediately added 172 PFAS to the list of chemicals covered by the TRI and provided a framework for additional PFAS to be added to TRI on an annual basis. This list became effective January 1, 2020, with the first PFAS Form Rs required by July 1, 2021. Eight additional PFAS have been added to the TRI list since then, bringing the current total to 180. |

| Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) | The Department of Defense (DOD) is phasing out AFFF and prohibits the use of AFFF during training exercises at military sites. | |

| Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) | Added Regional Screening Levels (RSL) for PFBS, GenX chemicals, PFOS, PFOA, perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), and perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) for Superfund sites. Note that RSLs are general screening levels, not cleanup standards.

Additionally, U.S. EPA has restarted the process of proposing to designate PFOA and PFOS as “hazardous substances”. |

|

| Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) | Initiated the process to propose adding PFOA, PFOS, PFBS, and GenX chemicals as “hazardous constituents” under Appendix VIII. Additionally, proposed clarification that the RCRA Corrective Action Program has the authority to require investigation and cleanup for wastes that meet the statutory definition of hazardous waste, as defined under RCRA §1004(5). | |

| Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) | Proposed rule requiring all manufacturers (including importers) of PFAS in any year since 2011 to report information related to chemical identity, categories of use, volumes manufactured and processed, byproducts, environmental and health effects, worker exposure, and disposal. | |

| Significant New Use Rule (SNUR) | Finalized for PFOA and PFOA-related chemicals. The SNUR requires notification from anyone who begins or resumes the manufacturing, including importing, or processing of these chemicals. The SNUR addresses risks from products like carpets, furniture, electronics, and household appliances. | |

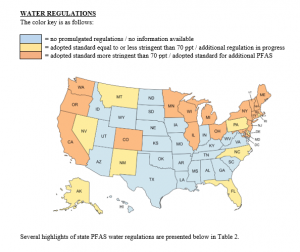

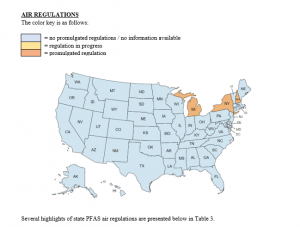

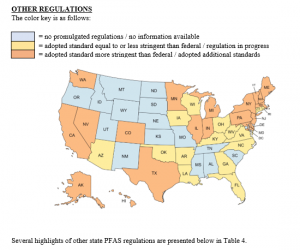

The following maps provide a high-level summary of what states are currently doing in terms of water, air, and other (e.g., AFFF, waste, consumer goods, remediation) PFAS-related regulations. This does not include any litigation, consent decrees, action plans/task forces, or investigative sampling.

Table 2

|

||

| State | Water Regulation Subcategory | Regulation |

| California | Drinking Water Notification Levels | PFOS (6.5 ppt), PFOA (5.1 ppt), and PFBS (500 ppt)

Note: The State Water Board has also requested notification levels for perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA), and 4,8-dioxia-3H-perflourononanoic acid (ADONA). |

| Drinking Water Response Levels | PFOS (40 ppt), PFOA (10 ppt), and PFBS (5,000 ppt) | |

| Colorado | Surface Water/Groundwater Translation Levels | PFOA + PFOS + PFNA (70 ppt, combined), PFHxS (700 ppt), and PFBS (400,000 ppt)

Note: The policy also includes monitoring and permitting considerations for entities that discharge to state waters. |

| Connecticut | Drinking Water Action Levels | PFOA (16 ppt), PFOS (10 ppt), PFNA (12 ppt), and PFHxS (49 ppt) |

| Delaware | Proposed Drinking Water MCLs | PFOS (14 ppt), PFOA (21 ppt), and PFOS + PFOA (17 ppt, combined). |

| Illinois | Drinking Water Health Advisories | PFBS (2,100 ppt), PFHxS (140 ppt), PFOS (14 ppt), PFOA (2 ppt), PFNA (21 ppt), and PFHxA (560,000 ppt).

Note: Illinois is also in the process of introducing groundwater quality standards and evaluating the need to introduce drinking water MCLs for several PFAS. |

| Maine | Interim Drinking Water MCLs | PFOS, PFOA, PFHpA, PFNA, PFHxS, and PFDA (20 ppt, combined)

Note: Maine also has monitoring requirements for PFAS. |

| Maryland | Drinking Water Health Advisories | PFHxS (140 ppt) |

| Massachusetts | Drinking Water MCLs | PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, and PFDA (20 ppt, combined) |

| Michigan | Drinking Water MCLs | PFNA (6 ppt), PFOA (8 ppt), PFHxA (400,000 ppt), PFOS (16 ppt), PFHxS (51 ppt), PFBS (420 ppt), and hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA) (370 ppt) |

| Minnesota | Drinking Water Health Advisories | PFOS (15 ppt), PFOA (35 ppt), PFHxS (47 ppt), PFBS (2,000 ppt), and PFBA (7,000 ppt) |

| New Hampshire | Drinking Water MCLs and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQS) | PFOA (12 ppt), PFOS (15 ppt), PFNA (11 ppt), and PFHxS (18 ppt) |

| New Jersey | Drinking Water MCLs | PFNA (13 ppt), PFOA (14 ppt), and PFOS (13 ppt) |

| Groundwater Quality Standards (GWQS) | PFNA (13 ppt), PFOA (14 ppt), PFOS (13 ppt), and chloroperfluoropolyether carboxylates (ClPFPECAs) (2,000 ppt, interim limit) | |

| New York | Drinking Water MCLs | PFOA (10 ppt) and PFOS (10 ppt) |

| North Carolina | Drinking Water Health Goal | GenX (140 ppt)

Note: This health goal has now been superseded by U.S. EPA’s health advisory of 10 ppt. |

| Proposed GWQS | PFOA and PFOS (70 ppt, combined). | |

| Ohio | Drinking Water Action Levels | PFOA and PFOS (70 ppt, combined), GenX (700 ppt), PFBS (140,000 ppt), PFHxS (140 ppt), and PFNA (21 ppt) |

| Oregon | Drinking Water Health Advisories | PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, and PFNA (30 ppt, combined) |

| Pennsylvania | Proposed Drinking Water MCLs | PFOA (14 ppt) and PFOS (18 ppt) |

| Rhode Island | Proposed Drinking Water MCLs | PFOA, PFOS, PFDA, PFNA, PFHxS, and PFHpA (20 ppt, combined) |

| Vermont | Drinking Water MCLs | PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA, and PFHpA (20 ppt, combined) |

| Washington | Drinking Water State Action Levels (SALs) | PFOA (10 ppt), PFOS (15 ppt), PFNA (9 ppt), PFHxS (65 ppt), and PFBS (345 ppt) |

| Wisconsin | Drinking Water MCLs | PFOA and PFOS (70 ppt; rule effective August 1, 2022) |

| Surface Water Standards | PFOS (8 ppt) and PFOA (20 ppt for public water supplies, 95 ppt for all other surface water). | |

Table 3

|

||

| State | Air Regulation Subcategory | Regulation |

| Michigan | Air Toxics | Allowable concentration levels (ACLs) set for PFOA and PFOS of 0.07 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m³), 24-hour average, individually or combined. New or modified sources that are required to obtain an air use permit are subject to Michigan’s air toxics rules, unless otherwise exempt. |

| New Hampshire | Air Toxics | Ambient air limits (AAL) set for ammonium perfluorooctanoate (APFO) of 0.05 µg/m³ (24-hour) and 0.024 µg/m³ (annual). New, modified, and existing processes are subject to the air toxics rule. |

| Best Available Control Technology (BACT) | BACT requirement for any facility that may cause or contribute to an AGQS or surface water quality standard (SWQS) exceedance of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) or precursors, which includes certain PFAS. | |

| New York | Air Toxics | Annual guideline concentration (AGC) set for PFOA of 0.0053 µg/m3. Any facility regulated under Part 212 must evaluate air contaminants, including PFOA, as applicable. |

Table 4

|

||

| State | Other Regulation Subcategory | Regulation |

| Alaska | AFFF/Hazardous Designation | Classified certain PFAS materials found in AFFF as “hazardous substances,” requiring notification and reporting. |

| Remediation | Soil and groundwater cleanup levels for PFOS and PFOA. | |

| California | AFFF | Reporting, notification, usage, and manufacturer requirements. |

| Consumer Goods | Restrictions on PFOA or PFOS-containing cosmetics, PFAS-containing food packaging, and PFAS-containing carpets and rugs that are manufactured in or imported to California. | |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Notification requirements for PFAS-containing PPE. | |

| Proposition 65 | Warning required for PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA. | |

| Colorado | AFFF | Usage and registration requirements for Class B firefighting foams. |

| PPE | Seller notification requirements for PFAS-containing PPE. | |

| Hazardous Designation | PFOA and PFOS added as “hazardous constituents” by the Solid and Hazardous Waste Commission. | |

| Delaware | AFFF | Proposed reporting, notification, and usage requirements. |

| Hazardous Designation | Policy adopted which classifies PFOA and PFOS as “hazardous substances.” | |

| Hawaii | Remediation | Interim soil and groundwater Environmental Action Levels (EALs) for certain PFAS. |

| Illinois | AFFF | Usage and manufacturer requirements. |

| Incineration | Bill to prohibit incineration of PFAS (with certain exceptions). | |

| Indiana | AFFF | Usage requirements. |

| Remediation | Screening levels for certain PFAS. | |

| Maine | AFFF | Proposed reporting, notification, and usage requirements. |

| Consumer Goods | Prohibition of PFAS-containing packaging, children’s products, carpets/rugs/fabrics, and pesticides. Prohibition of sale of any product containing PFAS that were intentionally added. | |

| Hazardous Designation | Changed definition of “hazardous substances” to include PFAS. | |

| Land Application | Prohibition of land application of sludge generated from municipal, commercial, or industrial wastewater treatment plants, compost produced from sludge, or any other materials derived from sludge. | |

| Remediation | Soil remedial action screening levels and water remedial action guidelines for PFBS, PFOS, and PFOA. | |

| Maryland | AFFF | Usage, discharge, and disposal requirements. Prohibition of intentionally added PFAS in Class B firefighting foam. |

| Consumer Goods | Prohibition of toxic flame retardants in furniture, mattress foam, and children’s products. Prohibition of intentionally added PFAS in rugs and carpets, and certain food packages and food packaging. | |

| PPE | Seller notification requirements for PFAS-containing PPE. | |

| Massachusetts | AFFF | AFFF collection and destruction program. |

| Hazardous Designation | PFAS are considered to be “hazardous material” subject to the notification, assessment and cleanup requirement. | |

| Land Application | PFAS monitoring requirements for residuals that have an Approval of Suitability (AOS) and are permitted to be reused through land application. | |

| Remediation | Established notification requirements and cleanup standards for PFAS in soil and groundwater. | |

| Michigan | AFFF | Discharge, usage, and reporting requirements. |

| Remediation | Groundwater cleanup criteria established for PFOS and PFOA. | |

| Minnesota | AFFF | Discharge and usage requirements. Prohibition of manufacturing and sale of PFAS-containing firefighting foam. |

| Consumer Goods | Prohibition of certain flame-retardant chemicals in certain types of furniture and children’s products. | |

| Nevada | AFFF/Consumer Goods | Restrictions on PFAS and additive organohalogenated flame retardants (OFR) used in textiles, children’s products, mattresses, upholstered residential furniture, and Class B firefighting foams. |

| New Hampshire | AFFF | Discharge and usage requirements. |

| PPE | Seller notification requirements for PFAS-containing PPE. | |

| New Jersey | AFFF | Proposed discharge and usage requirements. |

| Hazardous Designation | Addition of PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA to list of “hazardous substances.” | |

| New York | AFFF | Usage, notification, and incineration requirements. |

| Consumer Goods | Prohibition of PFAS additions in food packaging materials. Notification requirements for PFOS- and PFOA-containing children’s products. | |

| Hazardous Designation | PFOS and PFOA classified as hazardous substances. | |

| Pennsylvania | AFFF | Proposed discharge and use requirements. |

| Biosolids | Revised Biosolids General Permits to include PFOA and PFOS monitoring requirements (pre-draft issued). | |

| Remediation | Addition of groundwater and soil medium-specific concentration (MSC) for PFOA, PFOS, and PFBS. | |

| Texas | Remediation | Protective concentration levels (PCLs) set for 16 PFAS in groundwater and soil. |

| Vermont | AFFF | Takeback effort and proposed usage requirement. Restrictions on the use, manufacture, sale, and distribution of Class B firefighting foam containing PFAS. |

| Biosolids/Land Application | Solid waste rules that require PFAS testing for biosolids and for soils, groundwater, and crops at land application sites. | |

| Consumer Goods | Restrictions on the production, sale and distribution of food packaging to which PFAS have been intentionally added.

Restrictions on the manufacture, sale, and distribution of residential rugs and carpets to which PFAS have been intentionally added, as well as the use of after-market treatment products that contain PFAS.

Ban on the manufacture, sale and distribution of PFAS-containing ski wax, if the PFAS was intentionally added.

Inclusion of PFHxS, PFHpA, and PFNA on the list of chemicals of high concern to children. |

|

| Remediation | Groundwater/cleanup standards of PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFHpA, and PFNA. | |

| Washington | AFFF | Usage, notification, and manufacturer requirements. |

| Consumer Goods | Prohibition of PFAS additions in food packaging materials. Restrictions for PFAS-containing product categories including apparel and cosmetics. | |

| PPE | Notification for PPE containing PFAS. | |

ALL4 continues to track the regulatory movements and maintains a database of current state PFAS activity. If you have any questions about a specific state or would like any additional information, please reach out to Kayla Turney at kturney@all4inc.com.

U.S. EPA Finalizes Changes to Boiler MACT

The National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) for Industrial, Commercial, and Institutional Boilers and Process Heaters, which implements Maximum Achievable Control Technology (MACT) standards and is therefore also known as Boiler MACT, were promulgated on March 21, 2011, and amended on January 31, 2013, and November 20, 2015. Existing boilers and process heaters have been in compliance with the rule for several years now, and even new units (those for which construction commenced after June 4, 2010) feel like existing units at this point.

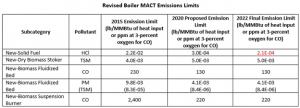

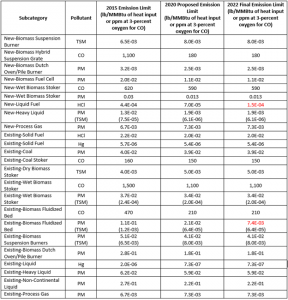

On July 21, 2022, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) signed a final rule that results in changes to the Boiler MACT in response to multiple court decisions. With the final rule, U.S. EPA is re-affirming two conclusions regarding carbon monoxide (CO) (that CO is a good surrogate for non-dioxin organic HAP and that a 130 ppm CO concentration threshold represents MACT for organic HAP for several subcategories), is revising many of the emissions limits, and is making other minor changes. Of the 34 revised emissions limits, 28 of the limits are more stringent than those in the previous version of the rule and six of the limits are less stringent. The technical corrections fix errors, improve clarity, and incorporate procedures into the rule for using carbon dioxide (CO2) instead of oxygen (O2) as a diluent.

What Emissions Limits Changed?

Table 1 of the preamble lists the limits that U.S. EPA is proposing to change based on their re-analysis of the dataset used in the 2013 rulemaking. For existing boilers, the changes to note are small reductions in the hydrogen chloride (HCl) and mercury limits for solid-fuel units, a reduction of the mercury limit for oil-fired units, and several changes to biomass-fired unit CO and particulate matter (PM) limits. The final revised PM limit for biomass-fired fluidized bed units is significantly more stringent. For new units, several proposed limits are also significantly more stringent than current limits, such as the HCl limits for new solid-fuel units and new oil-fired units. The table below lists the revised limits, three of which (highlighted in red) are more stringent than the 2020 proposal.

What Happens Now?

After the rule is published in the Federal Register, facilities will have three years to comply with the revised limits (this includes boilers and process heaters currently classified as new units). Facilities subject to the Boiler MACT should review the emissions limits and determine if compliance strategies may need to be adjusted. Is a new air emissions control strategy or a new fuel mix required? Should stack testing be used for compliance rather than fuel analysis?

Although we’ve seen several iterations of a Boiler MACT in the past two decades, even this change is not the last. U.S. EPA is also obligated to conduct a risk and technology review of the rule, and that review could lead to even more stringent requirements. In addition, there is always the chance that a petition for reconsideration could cause U.S. EPA to adjust the changes they finalized. ALL4 staff are keeping on top of these developments and can help you determine if you need to develop a strategy to comply with the revised emissions limits. Reach out to Amy Marshall or Anna Richardson for more information.

California OSHA – COVID-19 Prevention Emergency Temporary Standards – Extension

The California Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board (OSHSB) is the standards-setting agency within the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (better known as Cal/OSHA). On December 16, 2021, the OSHSB adopted revisions to the COVID-19 Prevention Emergency Temporary Standards (ETS) to include the latest recommendations from the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). The revisions took effect on January 14, 2022. The standard was re-adopted on May 6, 2022, and will be in effect through the end of 2022.

The following is a summary of changes to the ETS. (Note that this summary is not an all-inclusive description of the changes effective May 6, 2022.)

Four definitions were revised in the May 6th update, including close contact, infectious period, COVID-19 test, and fully vaccinated. Close contact and infectious period are now defined so that their meaning will change if CDPH changes its definition of the term in a regulation or order. COVID-19 test was revised to include self-administered and self-read tests. A video or observation of the entire test process is no longer necessary; a date/time-stamped photo of the test result will now be sufficient. Fully vaccinated was deleted as this term is no longer used in the regulations. All protections now apply regardless of vaccination status and ETS requirements do not vary based on an employee’s vaccination status.

Face coverings requirements have been revised.

- Requirements are the same for all employees regardless of vaccination status.

- Face coverings are no longer mandatory for unvaccinated workers in all indoor locations.

- Face coverings are mandatory in the ETS when CDPH requires their use regardless of vaccination status.

- Employers must review CDPH and local health department recommendations regarding face coverings and implement face covering policies that effectively eliminate or minimize COVID-19 transmission in vehicles. CDPH Masking Recommendations are periodically updated depending on the cases and transmission rates. The recommendations were last updated in April 2022.

- New requirement for employers to train employees on CDPH and local health department recommendations regarding face coverings and the employer’s policies. The timing and frequency of training should be outlined in your written COVID-19 Prevention Program.

Other Changes:

- Respirators must be provided for voluntary use to employees who request them and are properly cleared to wear them, and who work indoors or in vehicles with other persons regardless of vaccination status.

- COVID-19 testing must be made available to all employees with COVID-19 symptoms and to all employees regardless of vaccination status.

- Employers must review CPDH guidelines for employees who had close contact with individuals testing positive for COVID-19 and implement quarantine and other measures in the workplace to prevent COVID-19 transmission in the workplace.

- The requirements for employees who test positive for COVID-19 have been updated to reflect the most recent June 9, 2022, CDPH Isolation and Quarantine Guidance. Regardless of vaccination status, employees who test positive can return to work after 5 days if the employee has a negative test, symptoms are improving, and they wear a face covering at work for an additional 5 days. Otherwise, most employees can return 10 days following a positive COVID-19 test.

- Employees who had close contact with individuals testing positive must test negative or be excluded from the workplace until the return-to-work requirements for COVID-19 cases are met.

- Employers no longer need to consider the use of barriers or partitions to reduce COVID-19 transmission.

ALL4 is a full-service consulting firm specializing in health and safety plan issues. We are able to support you with COVID-19 program development and COVID-19 training. If you have any questions on how the ETS or other health and safety regulations affect your facility, please contact Bruce Armbruster at barmbruster@all4inc.com.

U.S. EPA Proposes Revisions to Gasoline Distribution Rules

On June 10, 2022, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) proposed revisions to 40 CFR Part 63, Subparts R and BBBBBB, the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) for Gasoline Distribution Facilities at major (Subpart R) and area (Subpart BBBBBB) sources of Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAP). U.S. EPA also proposed Subpart XXa, a new subpart to be added to the existing Part 60 New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) that will cover new, modified, or reconstructed bulk gasoline terminals.

With this rulemaking, U.S. EPA proposes new emissions limits, monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements for facilities. Facilities may need to revise existing compliance programs, consider upgrades to continuous monitoring systems (CMS) and/or data acquisition and handling systems (DAHS), and evaluate the need for physical modifications to comply with the proposed rules. Some of the key changes associated with the proposal include the following:

Loading Rack Emissions Limits

The proposed changes to Subpart BBBBBB include a lower emissions limit for loading racks at “large bulk gasoline terminals” (>250,000 gallon/day capacity) of 35 milligrams per liter (mg/L) of gasoline loaded. Subpart XXa will establish emissions limits for new and modified/reconstructed bulk gasoline terminals of 1 mg/L and 10 mg/L of gasoline loaded, respectively. Additionally, emissions limits specific to the type of control device used and the means of demonstrating compliance with those emissions limits have been included or referenced in each of the three revised rules as follows:

- Vapor Recovery Units (VRU): total organic carbon (TOC) concentration limits and continuous monitoring of TOC concentration

- Vapor Combustion Units (VCU): mg TOC/L gasoline loaded limits and continuous temperature monitoring

- Flares: meet the operational limits for refinery flares outlined in NESHAP Subpart CC. New terminals subject to Subpart XXa cannot use flares as a control device.

U.S. EPA proposes that bulk gasoline plants subject to Subpart BBBBBB that have a maximum design throughput of 4,000 gallons/day or more must install and operate vapor balance systems during loading and unloading of gasoline storage tanks and gasoline cargo tanks.

Equipment Leaks

U.S. EPA proposes to change the monitoring method for equipment leaks from monthly audio, visual, olfactory (AVO) inspections to instrument monitoring. The frequency of instrument monitoring depends on the applicable Subpart and can be quarterly, semiannually, or annually. Both Method 21 and optical gas imaging (OGI) are proposed as approved monitoring methods.

Storage Tanks

Facilities with storage tanks subject to Subpart R or Subpart BBBBBB currently must comply with portions of 40 CFR Part 60, Subpart Kb that are incorporated by reference. The proposed revisions to the rules align them closer with Subpart Kb, requiring controls on fittings for external floating roof tanks. Additionally, both Subparts include a proposed new requirement for internal floating roof tanks, prescribing that facilities maintain the vapor space above the floating roof at or below 25% of the lower explosive limit (LEL). Annual monitoring as part of existing visual inspections is proposed to demonstrate compliance.

In addition, gasoline storage tanks subject to Subpart BBBBBB with either a capacity less than 75 cubic meters (m3) or a capacity less than 151 m3 and a throughput less than 480 gallons/day must have a set pressure no less than 2.5 pounds per square in gauge.

Vapor Tightness Certification

The proposed rules synchronize the vapor tightness certification across the gasoline distribution rules to align with the approach currently specified in Subpart R. Expressed as a range, the numerical certification is dependent on the cargo tank compartment size.

Expanded Applicability of NESHAP Subpart R

Subpart R currently allows some bulk gasoline terminals and pipeline breakout stations to be excluded as an affected source based on the value of their emissions screening factor. The proposed revisions remove this exemption and require any bulk gasoline terminal or pipeline breakout station that is located at a major source of HAP to comply with this Subpart.

Miscellaneous Changes

In addition, the revised rules incorporate actions seen in other recent rulemaking activities, including the proposed removal of the startup, shutdown, malfunction (SSM) exemption, and the proposed adoption of electronic reporting for performance tests, performance evaluations, and semiannual reports.

How can I prepare?

Comments on the proposed rule are due August 9, 2022. Check with your industry association to see if they are commenting on the proposed rule, and consider adding your own comments, as U.S. EPA has requested comment on whether the proposed changes should be more stringent. Once the proposed rules are finalized, facilities will have up to three years to comply with the revised requirements following the date of publication in the Federal Register (up to 10 years for storage tanks, depending on when they are degassed). Although the compliance date seems far away, it’s not too early to evaluate current systems and start planning for any necessary upgrades.

If you have questions about how the proposed gasoline distribution rules may affect your facility, please reach out to me at klingard@all4inc.com. ALL4 continues to monitor this topic and is here to help your facility navigate these potential new requirements.

What to Know About Maryland’s New Storage Tank Regulations

The Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) updated Oil Pollution Control and Storage Tank Management regulation [Code of Maryland (COMAR) 26.10] became effective on June 13, 2022. The updates to COMAR 26.10 include the creation of new aboveground storage tank (AST) regulations and updates to Maryland’s underground storage tank (UST) regulation for consistency with the requirements of the 2015 revisions to 40 CFR Part 280.

What’s Required for My UST?

Many of the UST requirements under the 2015 revisions to 40 CFR Part 280 were already included under the previous COMAR 26.10 regulations. However, the June 13, 2022, updates require that UST owners in Maryland also:

- Complete inspections and functional tests of overfill prevention equipment (e.g., overfill alarms and automatic flow shut-off devices) at least every 3 years, with the first test being completed by an MDE-certified tester no later than June 13, 2023.

- Conduct periodic (i.e., monthly and annual) walkthrough inspections, starting no later than September 11, 2022. MDE has published its preferred monthly and annual walkthrough inspection checklists for facilities to use.

- Conduct containment sump tightness testing at least every 3 years (changed from every 5 years under the previous rule).

- Conduct inventory control as a method of release detection in addition to other forms of release detection used on the UST (e.g., automatic tank gauging, interstitial monitoring).

- Implement release detection and maintain records of release detection for UST systems that store oil solely for use by emergency power generators by October 13, 2022. This includes methods of release detection described above and release detection on piping (i.e., installing and testing leak detectors annually on pressurized piping, tightness testing suction piping at least every 2 years, and maintaining monthly records of release detection). USTs containing heating oil only for consumptive continue to not be required to perform release detection.

The updates to the UST regulations also include some clarifications on existing requirements, such as specifying that sump sensors used for interstitial monitoring must be placed within one inch of the lowest part of the sump.

How About my AST?

Under the previous COMAR 26.10 regulations, there were comparatively few requirements for facilities with ASTs with an aggregate oil storage capacity of less than 10,000 gallons (i.e., did not require an individual oil operations permit). The June 13, 2022, rule updates establish new requirements for shop fabricated and field constructed ASTs found at COMAR 26.10.17 and COMAR 26.10.18, respectively. Notable new requirements for shop fabricated ASTs [particularly those requiring action or are more stringent than Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC)] regulations include:

- Registering facilities with an aggregate regulated AST capacity of 2,500 gallons or more by December 13, 2023. ASTs excluded from registration and the requirements described below include those that have a capacity of 250 gallons or less, stores edible oils, and oil-filled operational equipment (e.g., oil-filled transformers and hydraulic elevator reservoirs).

- Conducting monthly and annual inspections, beginning no later than June 13, 2024. The inspection requirements generally follow the Steel Tank Institute (STI) Standard for The Inspection of Aboveground Storage Tanks (SP001), with the addition of needing to clean normal and emergency vents during the annual inspections (STI SP001 is typically used as the inspection standard for shop fabricated ASTs).

- Installing tank gauges (e.g., mechanical level gauge or automatic tank gauge) and a method of release detection (e.g., interstitial monitoring on double-walled ASTs) by June 13, 2024, and completing annual testing of the equipment.

- Meeting similar requirements to piping for UST systems if the AST system has underground piping.

- Maintaining records of routine inspections and testing for at least 5 years (note that this is more stringent than the SPCC requirement of maintaining records for at least 3 years). Records of integrity testing, repairs, spills, and other formal reports are required to be maintained for at least 5 years after permanent closure or removal of the AST system.

Note: the requirements described above apply to existing AST systems. AST systems that are installed on or after June 13, 2022, are required to comply with all of the above upon installation.

If you have questions on how these new regulations affect your facility, please feel free to reach out to me at sbharucha@all4inc.com or 571-392-2592 x505.

South Carolina Industrial Stormwater – On the Tides of Change

The South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (SCDHEC) has issued the Industrial Stormwater General National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permit (SCR000000) on May 26, 2022, and the permit became effective on July 1, 2022. Upon the permit’s effective date, a recertification Notice of Intent (NOI) is required from all existing coverage holders within the following 90 days. The 2016 permit expired on September 30, 2021, but remained effective until May 26, 2022, due to language in Section 1.3.2 of the 2016 permit. SCR000000 is based on United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) NPDES Multi-Sector General Permit (MSGP) for industrial stormwater, published on January 15, 2021.

There are four key updates to be mindful of with SCR000000 and all updates are consistent with information found in U.S. EPA’s MSGP.

- Addition of year 4 “checkups” to benchmark monitoring,

- Addition of year 4 “checkups” to impaired waters,

- Updates to benchmark values of metal pollutants, and

- Switch to uniform reporting periods for all permit Sectors.

SCR000000 now includes a fourth year “checkup” to quarterly benchmark monitoring. In addition to the existing benchmark sample collection during the first year of permit coverage, quarterly samples must now be collected during the fourth year of permit coverage as well. The purpose of the checkup is to verify that operators possess current industrial stormwater discharge and control measure data throughout the lifespan of the permit. In addition, potentially adverse effects from changes in facility operations can be more easily identified over the span of the permit. Lastly, the requirement is not impacted due to results found in the first three years of SCR000000 coverage – no matter what the results of the first year’s benchmark testing are each facility will still be required to sample again in the fourth year.

The new permit also adds a similar fourth year “checkup” for impaired waters monitoring. Impaired waters by definition do not have an U.S. EPA approved or established Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDL); this requirement is often referred to as Section 303(d) monitoring. Again, the requirement to sample in the fourth year is not impacted by monitoring results found in the first three years of SCR000000 coverage.

The permit has updated multiple pollutant benchmark values for metals, including cadmium, selenium, and silver. These changes have been made in accordance with the updated benchmark values from U.S. EPA’s updated MSGP. The value for selenium is now separated between flowing (lotic) and standing (lentic) Freshwater bodies. The values for cadmium and silver in Freshwater have been updated. While the Saltwater values for all three pollutants is unchanged from the 2016 permit.

The facility will use uniform reporting periods across all sectors within the numeric effluent limit discharge monitoring reports (DMR). This change removes the staggered reporting periods previously used in the 2016 permit. The quantity of DMRs is to remain stable for the near future and SCDHEC considers their number manageable for all coverage holders.

With the issuance of SCR000000 all existing coverage holders are required to submit a recertification of Notice of Intent (NOI). What is the due date for the NOI? The NOI is due within 90 days of SCR000000’s effective date (July 1, 2022) to maintain current NPDES stormwater coverage. All NOIs and permits are to be submitted electronically through ePermitting and be updated to meet compliance with SCR000000. Site’s stormwater pollution prevention plans (SWPPP) must also be updated to reflect changes to SCR000000.

ALL4 is tracking all SCDHEC industrial stormwater updates and is here to assist you and your facility with industrial stormwater compliance. If you have questions or concerns about SCR000000 compliance and renewal, please contact me at ages@all4inc.com or Anna Richardson at arichardson@all4inc.com.

Ambient Air Quality Regulatory Changes are Coming

The Clean Air Act (CAA) authorizes the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) to establish National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for certain air pollutants. The rules and regulations that implement the NAAQS are the foundation of State air quality management programs across the United States. Consequently, revisions to any of the NAAQS and changes to the NAAQS attainment status of a given region often result in negative consequences to both regulators and the regulated community.

There are two primary reasons for regulatory changes around the NAAQS. First, U.S. EPA is required to periodically review each of the NAAQS [e.g., sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NO2), ozone, lead, carbon monoxide (CO), particulate matter less than 10 microns (PM10), and particulate matter less than 2.5 microns (PM2.5)] and that review may result in a determination that the standards should be changed (i.e., become more stringent). A more stringent NAAQS can mean that it’s more difficult to get a permit for a new or modified facility and can mean extra regulatory requirements in areas that are not attaining a new NAAQS. U.S. EPA is currently reviewing the NAAQS for ozone, lead, and PM2.5.

Second, state and local regulatory agencies install and operate ambient air quality monitors to collect data and analyze whether areas are in compliance with the NAAQS. The monitoring data are used to determine whether areas are attaining the NAAQS. If areas that are not attaining the NAAQS do not improve air quality to attain the NAAQS within a certain amount of time, the classification (e.g., attainment or nonattainment) or the severity (e.g., marginal, moderate, serious, severe, and extreme) of the nonattainment can be changed, which results in significantly more stringent regulatory requirements and reductions of air permitting major source thresholds for nonattainment pollutants and their precursors [e.g., volatile organic compounds (VOC) and nitrogen oxides (NOX) emissions are precursors to ozone formation]. U.S. EPA recently proposed to reclassify six serious ozone nonattainment areas to severe ozone nonattainment and 31 marginal ozone nonattainment areas to moderate ozone nonattainment areas. These areas are located in different states across the U.S.

ALL4 will be hosting complimentary NAAQS webinars over the next few months to discuss these changes and their impacts to the regulated community. To discuss how these changes may affect your facility, please contact me or your ALL4 project manager.

Upcoming/Past Events (Recordings Available):

Should Your UST Be Included In Your SPCC Plan?

When most people think of the Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) plan for their facility, they think of their aboveground storage tanks (AST), their portable containers, and oil filled operational equipment. But how many think about their underground storage tanks (UST)?

For the most part, USTs are not regulated under SPCC regulations [i.e., Chapter 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 112 (Oil Pollution Prevention)] unless the facility’s aggregate underground storage is at or above 42,000 gallons. However, there are specific conditions that would cause a UST to be regulated under SPCC even if the underground storage threshold of 42,000 gallons is not met. These conditions include:

- The UST is at a facility that is already regulated under SPCC by reaching the above-ground regulated oil storage threshold of 1,320 gallons; and

- The UST is not subject to the technical requirements in 40 CFR Part 280 [Technical Standards and Corrective Action Requirements for Owners and Operators of Underground Storage Tanks (UST)]; and

- The UST is not subject to the technical requirements in an approved State program in 40 CFR Part 281 (Approval of State Underground Storage Tank Programs).”

- A supplementary graphic for clarity can be found here.

As an example, Facility B, an onshore, non-production facility in Florida, has 10,000 gallons of SPCC regulated aboveground storage as well as two USTs, both at 5,000 gallons and containing material that would qualify as SPCC regulated oil. UST1 is exempted from regulation under 40 CFR Part 281, since it contains heating oil for consumptive use; UST2 is not regulated under 40 CFR Part 280 or exempted from regulation under 40 CFR 281 as it is a single-walled diesel tank for emergency generators. UST2 isn’t in regulatory limbo; it is regulated under 40 CFR 112.

If your facility fits into the scenario above and the fundamental SPCC threshold is reached, each regulated container, including the one unique UST above, must have secondary containment per 40 CFR 112.7(c). If you have single-walled USTs, achieving the secondary containment requirement can be challenging and often results in the costly prospect of replacing the single-walled USTs with dual walled tanks. However, ALL4 has had success demonstrating equivalent secondary containment for single walled USTs by evaluating the absorptive and/or impermeable characteristics of the surrounding soil, assuming an adequate separation distance between the UST and underling groundwater. These situations are evaluated by reviewing the soil properties for the area and groundwater in the region to determine any possible routes for leaking oil from a UST to contaminate surface water through groundwater contamination.

In addition to the UST challenges discussed above, there are some other considerations even if your UST is regulated under 280 or exempted under 281, but you have an SPCC plan. For example, any UST transfer areas (loading or unloading) must be addressed in the SPCC plan, and the exempt USTs should be marked on the facility map as exempt from SPCC regulation.

Once the threshold of SPCC regulation is met, any oil container at or above 55 gallons should be considered when drafting your facility’s SPCC Plan, and this includes certain USTs. If you have any questions about SPCC plans or this article, reach out to Michelle Carter at mcarter@all4inc.com or Paul Hagerty at phagerty@all4inc.com.

NJDEP Proposes Environmental Justice Rule

New Jersey Department of Environmental Projection (NJDEP) has published a rule proposal for its Environmental Justice (EJ) program that would require facilities to address environmental and public health impacts they may have on overburdened communities (OBC) while obtaining a permit from the agency. In publishing these proposed rules, NJDEP has started a 90-day comment period set to expire on September 4, 2022.

Background Information

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) defines EJ as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental law, regulations, and policies.” In New Jersey, low-income communities have often been subject to a high number of environmental and public health stressors.

This proposed rule is the culmination of steps taken in New Jersey in September 2020 when the EJ Law was passed, which resulted in Administrative Order 2021-25 (AO) that granted the NJDEP the authority to deny or condition permits based on their effects on stressors to OBC. This action made New Jersey the first state to set standards, although other states are expected to follow suit. These proposed rules expand on the AO and would be published in the New Jersey Administrative Codes (NJAC) when finalized.

Who would this rule apply to?

NJDEP proposes to apply the rule to facilities that meet the following criteria:

- A designated facility, which is any:

- Major source of air pollution,

- Resource recovery facility or incinerator,

- Sludge processing facility, combustor, or incinerator,

- Sewage treatment plant with a “permitted flow” as defined in NJAC 7:24A-1.2,

- Transfer station or other solid waste facility, or recycling facility intending to receive at least 100 tons of recyclable material per day,

- Scrap metal facility,

- Landfill, such as those that accepts ash, construction or demolition debris, or solid waste, or,

- Medical waste incinerator, except certain medical waste incinerators.

- Located in an OBC, partially or fully, which is determined by census block groups where:

- At least 35% of households qualify as low-income,

- At least 40% of residents identify as a minority or members of a State-recognized tribal community, or

- At least 40% of households have limited English proficiency.

- Seeking a permit either for a new facility, to expand a facility, or for renewals of a Title V permit.

The EJ Law would give NJDEP the ability and requirement to deny permits for new facilities that would subject a community to adverse cumulative stressors (these are included in the Appendix to the proposed rules) and have a disproportionate impact on the OBC, or impose permit conditions for expansions or Title V renewals to limit their impacts on an OBC. The big picture approach is that the NJDEP is looking to compare a set of stressors for an OBC with those in non-OBC to determine if adverse cumulative effects are occurring in the OBC.

What would the process look like for affected facilities?

NJAC 7:1C-2.2 lays out a procedural roadmap for the process affected facilities would follow when applying for a permit.

- Initial Screen – When the applicant submits a subject permit application, the NJDEP would initially screen for OBC and stressor information. An applicant can also submit an Environmental Justice Impact Statement (EJIS) with the permit application, using information from the NJDEP Mapping, Assessment and Protection Tool (EJMAP).

- Preparation of EJIS –When the OBC is subject to adverse cumulative effects or would be as a result of a proposed project, the EJIS must be developed and show how the applicant would either avoid a disproportionate impact or how the project may serve a compelling public interest. This would be an extensive process, ideally involving the community long before any required public participation. Not specified in the rules but important to include is the positive impact the project and facility has had/will have. The submittal may include alternatives analyses, an assessment of control measures, and a facility-wide health risk assessment.

- Authorization to Proceed – After an initial review, the NJDEP will provide authorization to proceed to a meaningful public participation process pursuant to NJAC 7:1C-4.

- Meaningful Public Participation – This is a lengthy process a minimum of 60 days in duration, including a public hearing, a 30-day public comment period, and a potential for additional time if requested by the community or if material changes come from the public participation period, potentially resulting in a new comment period or hearing. It is important to have the support of the community at this step.

- Department Review – The NJDEP considers all information submitted by the applicant and the public.

- Department Decision – The NJDEP will either authorize the applicant to proceed and impose any additional permit conditions necessary to avoid disproportionate impacts, or deny the application.

Where can I find the proposed rule and comment?

A copy of the proposed rules can be found on the NJDEP website as part of a 153-page informational package. A summary of the steps is included on page 63, while the full text of the proposed rule starts on page 99.

The NJDEP will also be hosting public hearings in July. Information on how and where to attend these hearings is listed in the first page of the package.

Comments can be submitted electronically at www.nj.gov/dep/rules/comments. You should include the applicable NJAC citation and your name and affiliation. Paper comments can also be sent to the NJDEP, and oral testimony can be submitted prior to the virtual public hearing using the procedures listed in the package.

What should I do?

New Jersey facilities should review the EJMAP tool for their location to determine if there may be local EJ concerns. If the facility is in an OBC, check the other applicability requirements listed in the “Who would this apply to?” section – if the facility will be seeking a permit, is a designated facility in an OBC, and meets the criteria, this proposed rule would affect the facility. Going through this process will add a significant amount of time to the permit review process, so plan accordingly, begin looking at the EJIS requirements, and engage with your community, permit writers, consultants, and NJDEP EJ staff early and often to facilitate obtaining the permit. Reach out to ALL4 if you need assistance navigating these new requirements and planning how to address them.

How can I get additional information?

ALL4 is following this rulemaking and will continue to provide updates. If you have any questions or need additional information, please contact Corey Prigent at cprigent@all4inc.com or contact your ALL4 project manager.

Who Are the Typical Stakeholders in Environmental Health and Safety (EHS) Digital Solutions Implementations? What Are Their Goals and Interests?

One of the keys to successfully implementing a new EHS digital solution is to understand who the critical stakeholders are and their goals and priorities. Understanding who the stakeholders are while implementing a digital solution can help you include the correct resources on the project team. The intention of this article is to start the process of identifying these key stakeholders by describing some typical groups and their goals. Below are some examples of groups within your organization that may seek input on the implementation of a digital solution – note that not every digital solution rollout will involve all the groups below and sometimes specific groups will have different priorities than the examples listed below.

Corporate Users

Corporate users may include members from the executive leadership, corporate environmental, or the safety group. Corporate users could also be those who create and/or use a corporate report generated from the digital solution.

A corporate user’s primary goal may be that the data are transparent. Here are a few questions that stakeholders seeking transparency may ask.

- How easy is it to understand the source of the data or drill down to individual data points?

- How easy is it to understand what changes occur year over year and what causes those changes?

- Is the roll up of data into categories (perhaps by business line or geographic area) consistent and accurate enough to support corporate reporting or analysis?

- Does the system consistently handle data points for reporting? For example, is the system smart enough to not double count any data points?

Often corporate users have a goal that data be standardized across the organization. For example, sites with similar environmental compliance requirements should have a consistent number of compliance tasks, and the tasks should be named consistently across different sites. This allows a corporate user to compare data on the same basis (or “apples-to-apples” comparison). Consistent tasks across sites might allow a corporate user to search on a task name or keyword such as “inventory” to find all the tasks across sites related to emissions inventory reporting.

Site Users

Site users are those who support specific sites with their EHS compliance needs.

User adoption is one of the critical measures of success for a new digital solution, so site users and any other end users are key stakeholders. The primary goal for a site user is often ease of use. When the user is interacting with the system daily or weekly, ease of use will bring efficiencies to site personnel. When the user is accessing the system less frequently, an easier to use system will help the user to remember how to navigate and perform tasks.

Secondary goals for site users include:

- Easy-to-review summarized data, which may include dashboards or automatically generated summary emails to help users know information relevant to them, such as items requiring completion or approval.

- Minimizing duplicate user tasks.

- Customizing the tool to the site conditions.

- For example, site users often would like to have the language for compliance tasks to be specific to the site – including specific locations or site-specific descriptions of compliance.

- Inspections may have a site-specific checklist.

- Ensuring the system is comprehensive.

- For example, no overlooked compliance requirements or missing emissions calculations.

- Minimizing the steps needed to get data to its required final form, such as formatting for reporting.

IT Group

Some digital solutions require ongoing maintenance from the IT group (for example, rolling out upgrades to software tools). The IT group may also be a key stakeholder when it comes to integrating new digital solutions and existing systems such as PI ProcessBook, SAP, or Human Resources systems. In these cases, the IT group may also be a stakeholder.

Unsurprisingly, one of their primary goals may be ease of upkeep. For example, a tool that is closer to the standard out of the box configuration is often easier to upgrade than one that has been extensively customized. Another important consideration for IT groups is security. IT groups often have strict security-based requirements that can drive how a digital tool is implemented. IT groups also play a key role when integrating different systems such as personnel systems and system users or compliance tasking and work order systems.

Agencies

An agency can be state or federal, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) or the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). If the digital solution will be used to create a report or other direct deliverable for an agency, then the agency is an indirect stakeholder of the implementation. In rare cases where the creation of the system may be part of a consent decree or formal audit finding reported to a regulatory agency, that agency may actually be a direct stakeholder.

Agencies are not included on the project team, but the data or report produced by the tool is reported either directly or indirectly to the agency. The top priorities for agencies are that the information that is reported is complete and accurate, and all data is in the correct format per the agency specifications. One important thing to note is that agency data/reporting specifications can change over time, which sometimes requires the tool or system be updated to match the current requirements.

Summary

For the success of implementing a new digital tool, it is important to identify key stakeholders and their goals. Understanding typical stakeholders can help you include the correct stakeholders on the project team and help you address their concerns and goals. Not all stakeholders will be a direct part of the project team, but all critical stakeholder needs and priorities must be addressed as part of a successful implementation.

This blog has provided a brief discussion of typical stakeholders in a digital solution implementation. ALL4’s Digital Solutions Practice has extensive experience helping client’s scope, select, implement, maintain, and upgrade various types of digital solutions. If you would like to discuss a digital solution for your company, please contact Julie Taccino at jtaccino@all4inc.com or 281-201-1247.