Without Further Delay, the Final Risk and Technology Review for the Miscellaneous Organic Chemical Manufacturing NESHAP is Here (Almost)

The much-anticipated Final Risk and Technology Review (RTR) for the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP): Miscellaneous Organic Chemical Manufacturing, otherwise known as “the MON,” is finally here. Well, sort of. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) signed the final rule on May 29, 2020 and posted a pre-publication version on their website shortly thereafter. Although we’re still waiting on official publication in the Federal Register (and all the supporting information to be posted to the docket), affected facilities can do the following to start planning necessary changes to their operations now:

- Read the final rule! A red-line strike-out version of the rule will be available in the docket upon publication of the final RTR in the Federal Register, and while it’s easier to identify changes in the rule using a red-line version, we recommend reading the pre-publication version now to get a head start on any action you need to take.

- Evaluate how the new requirements for ethylene oxide described below will affect you. Do you need to gather additional data?

- Plan projects that will be required for compliance. Develop a timeline and schedule. Can you accommodate these projects into an already planned outage such that the compliance deadline can be met?

- Affected sources that started construction after December 17, 2019 must be in compliance with the new requirements on startup, or when the final rule is published in the Federal Register, whichever is later.

- Existing sources must be in compliance with the new EtO control standards within 2 years of publication, the new equipment leaks standards within 1 year of publication, and the new heat exchange system and gap filling provisions (e.g., SSM and maintenance vents) within 3 years. Electronic reporting of performance tests and evaluations is required within 60 days of publication of the final rule, and the requirement to monitor new or replaced equipment for leaks is effective upon publication of the final rule.

- Identify what air permitting, if any, will need to be completed to support possible capital projects.

- Determine what additional information must be monitored and recorded to comply with the revised monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements.

- Determine what internal procedures and plans need to be updated as a result of the rule changes.

What are the Most Significant Changes?

Two of the most significant changes are almost identical to those we have seen in other rules: revised flare requirements and work practices for pressure relief devices (PRD). However, the most notable changes U.S. EPA finalized are those related to control of ethylene oxide (EtO) emissions.

U.S. EPA found that risks from the source category unacceptable due, in part, to emissions of EtO from process vents, storage tanks, and equipment leaks. The results of the Agency’s risk assessment were largely influenced by the 2016 unit risk estimate (URE) for EtO from U.S. EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). U.S. EPA solicited and received several comments on the use of the IRIS value, and ultimately decided to continue using the IRIS value while noting that the Agency is “open” to new values such as the dose response value finalized by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) on May 15, 2020. Although the Agency explained the TCEQ value was not available in time for consideration in the final rulemaking, it’s unclear whether U.S. EPA has any intent to further evaluate risks with a revised URE for EtO at this time.

On top of additional controls to address risk from EtO emissions, U.S. EPA finalized other changes to address startup, shutdown, and malfunction (SSM) events consistent with the 2008 vacatur of the SSM exemptions in the 40 CFR Part 63 General Provisions. The U.S. EPA also promulgated changes as a result of their technology review and revisions to incorporate electronic reporting requirements.

Miscellaneous Organic NESHAP (MON) Update Webinar

New Standards for Ethylene Oxide Emissions

The final rule contains new standards for process vents, storage tanks and equipment in EtO service. For purposes of the MON, “in ethylene oxide service” for equipment leaks means any equipment that contains or contacts a fluid that is at least 0.1% by weight EtO. Process vents in EtO service are those vents that when uncontrolled contain more than 1 part per million (ppmv) by volume of EtO and, when combined, would emit 5 pounds per year or more of EtO. Additionally, any tank storing a liquid that is at least 0.1% by weight of EtO is considered in EtO service. For vents, storage tanks, and equipment, if information exists that suggests EtO could be present, then the source is considered to be in EtO service unless sampling and analysis is performed to demonstrate otherwise.

For process vents and storage tanks, facilities must vent emissions to a control device that either reduces EtO by 99.9% by weight or to less than 1 ppmv for each process vent and storage tank. An additional option for process vents is to reduce emissions to less than 5 pounds per year of EtO for all combined process vents.

If you choose to comply with the 99.9% by weight reduction standard, or the 5 pounds per year standard for process vents, you must conduct initial performance testing and establish operating parameter limits for your control device. Periodic testing is required every 5 years to demonstrate compliance and reestablish operating parameter limits. Alternatively, if complying with the outlet concentration option (i.e., 1 ppmv of EtO), facilities may use a continuous emissions monitoring system meeting the requirements of Performance Specification 15 of 40 CFR Part 60, Appendix B instead of conducting initial and periodic performance testing.

Any storage tank considered a pressure vessel that is in EtO service must operate with no detectable emissions and must be monitored annually for leaks. Any reading greater than 500 ppmv is considered a deviation. Additionally, the pressure vessel must be operated as a closed system that vents to a control device meeting the requirements described above.

For equipment in EtO service, facilities must monitor all pumps in EtO service monthly using a leak definition of 1,000 ppmv and any leaks must be repaired within 15 days of being detected. Connectors must be monitored annually using a leak definition of 500 ppmv and any leaks must also be repaired within 15 days. If any light liquid pumps or connectors in EtO service are added to a source or replaced, facilities must monitor within 5 days of starting up the new equipment.

PRDs in EtO service must comply with the new monitoring and work practice provisions for PRDs described below with a few exceptions. Most notably, any release event from a PRD in EtO service is considered a deviation.

Changes as a Result of the Technology Review

U.S. EPA did not identify any cost-effective developments for process vents, storage tanks, transfer racks, or wastewater as part of the Agency’s technology review; however, the final rule contains revised standards for heat exchange systems and equipment leaks.

Similar to the recent RTR rule for the Ethylene Production NESHAP at 40 CFR, Part 63, Subpart YY, the final MON rule requires quarterly monitoring for heat exchange systems at existing sources and monthly monitoring at new sources using the Modified El Paso Method and a leak definition of 6.2 parts per million by volume (ppmv) of total strippable hydrocarbon in the stripping gas. U.S. EPA included an alternative leak definition for systems with a recirculation rate of 10,000 gallons per minute or less of 0.18 kilograms per hour (kg/hr) of total hydrocarbon emitted from the heat exchange system. Any leaks above a delay action level must be repaired within 30 days. The delay action level is 62 ppmv, or 1.8 kg/hr for systems with a recirculation rate less than 10,000 gallons per minute. The Agency also added a definition of “heat exchange system” to the rule.

For equipment leaks, U.S. EPA lowered the leak definitions for light liquid pumps at existing batch processes from 10,000 to 1,000 ppmv with monthly monitoring. The Agency also added provisions that require facilities to monitor any new or replaced equipment within 30 days after initial startup if the equipment is subject to the MON equipment leak standards and is otherwise required to be monitored using EPA Method 21.

Revisions to Address Regulatory Gaps

Pressure Relief Devices

The MON now contains monitoring and work practice requirements for PRDs similar to those in the Refinery RTR rule at 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart CC and the Ethylene RTR rule at 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart YY. The final rule includes requirements to develop a PRD management program, monitor PRDs for releases, and perform root cause and corrective action analyses after a release. Several types of PRDs are exempt from the work practice requirements and facilities should carefully review the list of exemptions to determine which of their PRDs must comply with the new work practices. U.S. EPA also finalized a requirement that new pilot-operated PRDs must be the “non-flowing” type (pilot valve discharge does not vent continuously during an event).

Bypass Lines, Maintenance Vents, and Storage Tanks

U.S. EPA finalized the requirement that facilities may not bypass a control device at any time. If bypass occurs, facilities must include the details of each bypass, including the total quantity of organic HAP released, in the semiannual periodic report.

The final rule also contains requirements for maintenance vents that are used as a result of startup, shutdown, maintenance, or inspection of equipment where equipment is emptied, depressurized, degassed, or placed into service. To comply with the maintenance vent provisions, prior to venting, facilities must remove process liquids and depressurize equipment to a flare or control device until one of several control criteria are met (e.g., the vapor is below 10% of the LEL). The maintenance vent provisions are similar to those for refineries and ethylene production facilities, but the MON contains an option for equipment containing hydrogen halide and halogen HAP. Equipment that contains hydrogen halide or halogen HAP is allowed to vent to the atmosphere if the vapor in the equipment has an LEL of less than 10% and the outlet concentration of hydrogen halide and halogen HAP is less than or equal to 20 ppmv.

Like the Agency did for the Ethylene RTR, U.S. EPA added storage tank degassing requirements as well. Emissions from degassing must be controlled until the vapor space concentration is less than 10% of the LEL, for both fixed and floating roofs. Emissions must be controlled using a flare, a non-flare control device, or routed to a fuel gas system or process.

Flares

The final rule contains significant amendments to the operating and monitoring requirements for a subset of flares used as control devices. U.S. EPA determined that the current requirements are not adequate to ensure the level of destruction efficiency needed to conform with the standards (98% destruction) for flares controlling emissions from sources in EtO service, or from manufacturing chemical process units (MCPU) that produce olefins or polyolefins. Like the recent Ethylene RTR, these flares are now subject to the Refinery RTR flare definitions and requirements in 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart CC. In the final rule, U.S. EPA clarified that MCPUs that produce olefins or polyolefins includes only those MCPUs that manufacture ethylene, propylene, polyethylene, and/or polypropylene as a product (by-products and impurities are not considered products).

The subset of flares must operate with a pilot flame at all times and be continuously monitored. Each 15-minute block where there is at least 1 minute where no pilot flame or flare flame is present when regulated material is routed to the flare will be a deviation from the standard. Visible emissions are allowed for no more than 5 minutes in a 2-hour period and facilities must monitor for visible emissions on a daily basis. Additional observation periods are required if visible emissions are observed.

U.S. EPA incorporated the 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart CC requirements for maximum flare tip velocity into the MON as a single equation, irrespective of flare type and facilities must comply with a single minimum operating limit for the net heating value in the combustion zone gas of 270 Btu/scf during any 15-minute period.

The final rule also contains specific requirements for pressure assisted multi-point flares (MPF) in the aforementioned subset. MPF are not required to comply with the flare tip velocity requirements in 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart CC but must operate with a net heating value in the combustion zone gas of 800 Btu/scf on a 15-minute average basis. If the MPF uses cross-lighting instead of a pilot on each burner, each burner must be no more than 6 feet apart (unless a cross-lighting demonstration is conducted) and each stage must operate with a flame present with regulated material is routed to the stage. Each stage must have at least two pilots with one continuously lit. A deviation occurs if there it at least one minute in a 15-minute block where no pilot flame is present on a stage of burners when regulated material is routed to the stage. Facilities must also monitor the main flare header pressure and valve positions for each stage to ensure proper operation. An MPF can continue to operate under an approved alternative means of emissions limitations (AMEL) in lieu of the new MON requirements.

As in the proposed rule, facilities must comply with 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart CC visible emissions work practices for emergency situations; however, as a change from proposal, facilities may not comply with the work practices for velocity limit exceedances during emergencies and instead must comply with the flare tip velocity limits at all times.

The final rule clarifies overlap of the MON standards with other flare regulations. Flares that are subject to 40 CFR §60.18, §63.11, or §63.987 but that comply with the new standards for flares in the MON rule are only required to comply with the MON. Except for MPF, flares subject to 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart CC and used as a MON control device are required to comply only with 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart CC flare requirements.

Non-regenerative Adsorbers and Adsorbers Regenerated Off-site.

The final MON RTR rule now contains provisions for facilities that use non-regenerative adsorbers and adsorbers regenerated off-site as control devices. If a facility uses these types of adsorbers, they must operate at least two adsorbers in series. Operators are required to establish the bed life of the adsorbers based on either a performance test or design evaluation, and the first bed must be continuously monitored for breakthrough according to a specified schedule. If the adsorbent has more than 2 months of life left, facilities must monitor for breakthrough monthly. If the bed life is between 2 months and 2 weeks, monitoring is required on a weekly basis. If the bed has 2 weeks or less of life remaining, daily monitoring is required. When breakthrough is detected, operators must replace the first bed with the second, and install a new bed in place of the second.

Other Changes

The final rule contains several other changes including revisions and additions to the definitions, updated overlap provisions, and new recordkeeping and reporting requirements (including electronic reporting requirements). U.S. EPA also finalized clarifying text and corrections to typographical errors, grammatical errors, and cross-reference errors.

How can ALL4 Help?

ALL4 has a variety of chemical sector experience, including the MON. We are well versed in the Refinery RTR flare requirements and can assist MON facilities with the new flare requirements including developing monitoring plans, identifying required monitoring systems, and/or preparing procurement specifications for equipment suppliers. We can also help facilities analyze, plan for, and comply with the new requirements for heat exchange systems, PRDs, and other emissions sources. Contact Philip Crawford at 984-777-3119 or your ALL4 project manager with questions.

Recent Updates to the MATS Rule

There were two recent Federal Register notices related to the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) for Coal- and Oil-Fired Electric Utility Steam Generating Units (EGUs), commonly referred to as the “Mercury and Air Toxics Standards” (MATS). Each action, along with some background, is provided below.

Eastern Bituminous Coal Refuse-fired Electrical Generating Units – New Hazardous Air Pollutant Emissions Limitations

The MATS rule was proposed on May 3, 2011 and finalized on February 16, 2012, under 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart UUUUU (Subpart UUUUU). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) originally promulgated a single acid gas Hazardous Air Pollutant (HAP) emissions standard for all coal-fired EGUs using hydrochloric acid (HCl) as a surrogate for all acid gas HAP, as well as an alternative emissions standard for sulfur dioxide (SO2) as a surrogate for the acid gas HAP that may be used if a coal-fired EGU is operating some form of flue gas desulfurization (FGD) system and an SO2 continuous emissions monitoring system (CEMS). Since the original publication of MATS and following a series of petitions and requests for reconsideration, U.S. EPA acknowledged that there are differences in HAP emissions profiles based on the type of coal refuse fired. Specifically, U.S. EPA recognized that there are differences between anthracite coal refuse and bituminous coal refuse, and additionally between western and eastern bituminous coal refuse (WBCR and EBCR, respectively). This distinction is the basis for the Final Rule “NESHAP: Coal- and Oil-Fired EGUs—Subcategory of Certain Existing EGUs Firing Eastern Bituminous Coal Refuse for Emissions of Acid Gas HAP” effective April 15, 2020 (85 FR 20838). With this action, U.S. EPA proposed the establishment of a new subcategory for EBCR-fired EGUs to reflect the different coal refuse emissions profiles.

After receiving public comments supporting the proposal and evaluating emissions data available when the 2012 MATS rule was established, in addition to new data provided in recent years, U.S. EPA is establishing a new subcategory for certain existing EBCR-fired EGUs for emissions of acid gas HAP. With the Final Rule, U.S. EPA is establishing a specific maximum achievable control technology (MACT) floor and a new emission standard applicable to the subcategory.

Does this rule apply to my facility?

The Final Rule defines the new, very limited, subcategory as “any existing (i.e., construction was commenced on or before May 3, 2011) coal-fired EGU with a net summer capacity of no greater than 150 megawatts (MW) that is designed to burn and that is burning 75 percent or more (by heat input) EBCR on a 12-month rolling average basis.” The new acid gas emissions limitations for EBCR-fired EGUs are as follows:

HCl – 0.04 pounds per million British thermal units (lb/MMBtu) or 0.4 lb/MW-hr

OR

SO2 – 0.6 lb/MMBtu or 9.0 lb/MW-hr

There are six EBCR-fired EGUs in the new subcategory that are operating near legacy piles of EBCR in two states:

- Pennsylvania:

- Colver Power Project (110 MW Summer Capacity; located in Colver)

- Ebensburg Power (50 MW Summer Capacity; located in Ebensburg)

- Scrubgrass Generating Company LP Unit 1 and Unit 2 (42 MW Summer Capacity each; located in Kennerdell)

- West Virginia:

- Grant Town Power Plant Unit 1A and Unit 1B (40 MW Summer Capacity each; located in Grant Town)

Sources must be in compliance with the applicable HCl and SO2 limitations upon the effective date of the Final Rule (i.e., no later than April 15, 2020). No later than 180 days after the compliance date, sources must demonstrate compliance has been achieved by conducting the required tests and then must make the required notifications. If an HCl or SO2 CEMS is initially used to establish compliance, the initial performance test consists of 30 boiler operating days of CEMS data. The sustained compliance with the newly established emissions limits is required to be verified on a 30-boiler operating day rolling average.

Can EBCR-fired EGUs meet the new limits?

The limits in this new subcategory are quite a bit higher than the current limits included in the MATS rule for other existing coal-fired EGUs (2.0E-03 lb/MMBtu or 0.02 lb/MWh for HCl and 0.2 lb/MMBtu or 1.5 lb/MWh for SO2). The new subcategory was created to specifically address the ability of EBCR-fired EGUs to comply with the MATS acid gas limits. The revised emissions limits were established based on emissions rates that the currently operating EBCR-fired EGUs have achieved and are consistent with EPA’s 90 percent SO2 reduction target. Sulfur and chloride contents of eastern bituminous coal are higher than anthracite or coals from other regions of the U.S so combustion of EBCR leads to higher emissions of SO2 and HCl than combustion of other coal types.

Coal refuse fuels are fired in fluidized bed combustors that use limestone in the bed, which provides control of acid gases. However, there is a limit to the amount of solid material that can be in a combustor at one time, and U.S. EPA admitted that injecting large amounts of limestone could result in a decrease in the amount of coal refuse a unit is able to fire, with a corresponding decrease in steam and power production. In addition, increased use of sorbents in the bed or injected into the ductwork could alter the characteristics of the fly ash and prevent beneficial reuse. With the new emissions limitations, there is no longer a need for additional acid gas control technology or fuel switching in EBCR-fired EGUs.

Reconsideration of Supplemental Finding and Residual Risk and Technology Review

The Clean Air Act (CAA) required U.S. EPA to analyze HAP emissions and perform a risk assessment to inform a determination of whether it was “appropriate and necessary” to regulate HAP emissions from EGUs. U.S. EPA originally determined in December 2000 that it was appropriate and necessary to regulate coal- and oil-fired EGUs under CAA Section 112. However, U.S. EPA reversed course in 2005 and instead promulgated the Clean Air Mercury Rule (CAMR) under CAA Section 111. The D.C. Circuit Court vacated the 2005 actions and the U.S. EPA then completed additional analyses, found again that it was appropriate and necessary to regulate HAP emissions from coal- and oil-fired EGUs, and promulgated the MATS rule in 2012. Litigation resulted in a U.S. Supreme Court Decision in 2015 that U.S. EPA should have considered cost in its analyses. As a result of that decision, U.S. EPA published a reconsideration of its finding in the Federal Register on May 22, 2020 (85 FR 31286). The revised finding is that it is not “appropriate and necessary” to regulate EGUs under section 112 of the Clean Air Act (CAA) because the costs of the regulation outweigh the benefits of the emissions reductions when only the HAP emissions reductions are considered. However, U.S. EPA did not revoke the MATS rule as part of the finding.

U.S. EPA also finalized the results of the Risk and Technology Review (RTR) of MATS that the Agency is required to conduct within eight years of finalizing each NESHAP. U.S. EPA performed a risk assessment and determined that the residual risks from emissions of HAPs from the coal- and oil-fired EGUs source category are acceptable and that the current standards provide an ample margin of safety to protect public health and prevent an adverse environmental effect. The technology review determined that there are no new developments in HAP emissions controls that would achieve further cost-effective emissions reductions. Therefore, no changes to the standards are necessary as a result of the RTR.

Although the new EBCR subcategory affects only a small number of regional plants across the country, it will prove to be extremely beneficial, both economically and environmentally, to these sources. That the RTR did not indicate U.S. EPA should make the MATS rule any more stringent was a good result for facilities complying with the rule, but the determination that it was not appropriate and necessary to establish the MATS rule in the first place has sparked legal action and we are waiting to see how that plays out. The MATS rule resulted in significant emissions reductions in both criteria pollutants and HAPs, and a court could determine that the rule should be vacated since U.S. EPA has now determined it was not appropriate and necessary. If you have any additional questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out to David Ross at dross@all4inc.com or 610-933-5246 ext. 103.

Utah Emissions Reporting: Change is in the Air

As Bob Dylan says, the times, they are a-changin’. Amidst the COVID-19 concerns and considerations that are ongoing, the changes don’t stop there for those who operate in Utah. The Utah Department of Environmental Quality (UDEQ) has proposed to update the air Emissions Inventory Rule at R307-150. UDEQ has also provided a summary of the proposed rule changes. The proposed updates fall into two categories: ozone nonattainment and procedural updates. Each category of changes is discussed below.

The first set of changes revolves around the August 2018 designation from U.S. EPA that the counties of Davis, Weber, Salt Lake, Utah, and a portion of Tooele are in nonattainment with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for ozone. The portion of Uinta Basin, located in Duchesne and Uintah Counties, at 6,500 feet above sea level or below was also designated as ozone nonattainment. In order to obtain additional information about the sources contributing to the NAAQS nonattainment, UDEQ has proposed to require sources within the nonattainment area which have the potential to emit 25 tons per year of nitrogen oxides (NOX) or volatile organic compounds (VOC) to report NOX and VOC emissions annually. NOX and VOC are the primary contributors for the formation of ground-level ozone.

The second set of changes is intended to improve the emissions reporting process and is more broadly applicable to the regulated community. Emissions inventories are required to be submitted annually for large major stationary sources [i.e., major stationary sources with the potential to emit 2,500 tons or more of NOX, oxides of sulfur (SOX), or carbon monoxide (CO) or that has the potential to emit 250 tons or more of particulate matter either 10 micrometers or 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter (PM10 or PM2.5), VOC, or ammonia]. Title V sources that are not classified as large major sources must submit emissions inventories every three years.

Currently, Title V sources are required to submit either a summary only inventory or a detailed inventory, depending on the location of the source and/or the potential to emit from the source as outlined in R307-150-7. The proposed changes would require all Title V sources required to submit an emissions inventory to submit a detailed inventory, regardless of location or potential to emit. Facilities changing from a summary only inventory to a detailed inventory report will need to work with UDEQ to reconcile the inventory of emissions units. UDEQ staff plan to work with the affected facilitates to complete the emissions unit inventory reconciliation in preparation for reporting year 2020 activity.

The proposed changes would become effective for reporting year 2020 (i.e., the first report under the amendments will be due April 15, 2021). UDEQ intends to use the existing tools in place for the emissions inventories [i.e., the Statewide and Local Emission Inventory System (SLEIS), or the Centralized Air Emissions Reporting System (CAERS) for oil and gas sources] as the avenue for this submittal. The changes were discussed at a Utah Air Quality Board meeting on June 3, 2020. The rule is now under the public comment period, which ends on July 2, 2020 and for which a public hearing is scheduled on August 3, 2020.

Of course, we will continue to track the ch-ch-ch-ch-changes (thanks David Bowie!). If you have any questions or need assistance, please contact me at scunningham@all4inc.com or (610) 422-1144.

TCEQ’s Expedited Permitting Program Update

ALL4 has been tracking Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s (TCEQ’s) Expedited Permitting Program since being rolled out in November 2014. ALL4’s historic blog on the expedited permitting program is located here. After some revisions to the program in 2019, we found it appropriate to provide an update to the blog, as well as share our experiences with the expedited permitting program, itself.

The 2019 developments to the program can be distilled down in the Senate Bill (SB) 698, which was signed by the Governor on June 2, 2019 with an effective date of September 1, 2019. A summary of the SB 698 along with a summary of environmental highlights of the 86th Texas Legislative Session can be found here. As a result of SB 698, Section 382.05155 (Expedited Processing of Application) of the Health and Safety Code was required to be updated. Following the update to Section 382.05155, a rulemaking with an effective date of May 28, 2020 amended 30 TAC §101.601 to align TCEQ’s rules with the state law. Therefore, 30 TAC §101.601 has been updated to reflect the statute’s language where a surcharge for an expedited application fee may be determined in amounts sufficient to cover expenses incurred by the expediting of permit applications (e.g., overtime, costs of full-time equivalent commission employees, contract labor, etc.).

See below for general details regarding TCEQ’s Expedited Air Permitting Program. The list below has been updated from our historical details list first published in 2014 where needed with those updates marked with an underline.

- TCEQ Organization: TCEQ now has siloed the Expedite Team under the Mechanical/Coatings New Source Review Permits Section within the Air Permits Division.

- Application: Applicants must file a new “Expedited Permitting Request” form and cover letter with the application: “Form APD-EXP.” For companies that have pending applications that wish to take part in the expedited program, Form APD-EXP and a cover letter, should be submitted to the Air Permits Initial Review Team (APIRT). As a general reminder, be sure to update the Materials tab on the PI-1 Form to reference the associated Form ADP-EXP and other forms associated with expediting the application.

- ePermits: Applicants must use TCEQ’s ePermits for permits by rule (PBRs) and standard permits that are not subject to public notice. While not required, TCEQ encourages other permit applications to also use the ePermitting mechanism. With the application submittal, Form APD-APS is required to be submitted to TCEQ’s cashiers’ s office along with the payment. Confidential information can now be submitted through ePermits. Confidential information is to be separated from the rest of the application materials and marked as Confidential within the State of Texas Environmental Electronic Reporting System (STEERS).

- Acceptance/Denial: TCEQ will accept or deny the expedited request and will notify the entity via email. For any project that is denied, the surcharge amount will be returned to the permitting party.

- Surcharge: Initial surcharges range from a flat rate non-refundable $500 for PBRs and Standard Permits (not requiring public notice) to $20,000 for Federal New Source Review (NSR) Permits – PSD including greenhouse gases (GHGs), Nonattainment NSR, Plantwide Applicability Limits (PAL). Standard Permits and Title V General Operating Permits (GOP) are $3,000, while Title V Site Operating Permit (SOP) and case by case NSR permits are $10,000. [Note: there is no additional fee for an NSR case-by-case permit, which accompanies a Federal NSR Permit; only the Federal NSR permit surcharge applies.]

- Refunds: TCEQ will issue refunds for projects with a remaining surcharge balance amount of $450 or more. No refunds will be issued for PBRs and standard permits with no public notice. Conversely, TCEQ will notify the applicant prior to the initial surcharge amount being depleted. The applicant can choose to provide additional funding or if the applicant elects not to provide additional funding to continue with the expedited process, the application will revert to a non-expedited project and will be reviewed according to standard agency timeframes and may be assigned a different reviewer.

- Timing: TCEQ qualifies the time to complete the air permit as dependent on many factors: APD workload, staff availability, application complexity, public participation, application completeness and thoroughness (i.e., sufficient administrative and technical detail). No specific timing has been provided by TCEQ to date; however, TCEQ identifies a lag of applicant responsiveness and technical or administrative deficiencies common reasons why projects can be delayed.

- Recommendations: TCEQ suggests (and ALL4 agrees) several actions to speed up the process. Hold a pre-application meeting to discuss the project, regulatory applicability including beset available control technology (BACT), air dispersion modeling, project timing, etc.

ALL4 has experience working through TCEQ’s expedited permitting process. Throughout the years, we have guided and advised our clients on their projects, starting from the initial preapplication meeting through the end of the second public notice to final permit issuance. Being timely in responding to TCEQ inquiries on the application, as well as delivering a comprehensive application that addresses anticipated TCEQ questions, all increase the efficiency of a permit review, ultimately decreasing the time until permit issuance. While TCEQ remains reluctant to identify specific timelines associated with expedited permits, following the advice and approach discussed above, ALL4 has permitted a client’s greenfield project with TCEQ in approximately five months.

TCEQ’s official Implementation of the Expedited Permitting Program can be found on Air Permit Reviewer Reference Guide (i.e., APDG) 6258v7, located here, as revised in June 2019. If you have further questions about the expedited Permitting Program, please reach out to me, Frank Dougherty at fdougherty@all4inc.com or 281-937-7553×302.

Final Revisions to Plywood and Composite Wood Products (PCWP) Rule Signed

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has been working through several required Risk and Technology Reviews (RTRs) of National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP). One of the latest RTRs to be finalized is the PCWP NESHAP. This rule is promulgated at 40 CFR Part 63, Subpart DDDD, and covers wood products plants that are major sources of hazardous air pollutants (HAPs). The original rule was finalized in 2004, reconsidered and revised in 2006, and revised due to a court decision in 2007. The latest revisions to the rule were signed on June 8, 2020 and have not yet been published in the Federal Register. U.S. EPA determined that risk from PCWP facility air emissions is acceptable and that public health is protected by the current NESHAP with an ample margin of safety. However, there were several revisions and clarifications made to the PCWP NESHAP requirements. The most significant revisions are discussed below. Other revisions to note include adjustments to the non-HAP coating definition, the temperature sensor validation requirements, and excess emissions reporting.

Startup, Shutdown, and Malfunction (SSM)

U.S. EPA has been removing SSM provisions from NESHAP as part of all of its RTRs. The original SSM exemptions and SSM plan requirements have been removed from the revised PCWP NESHAP, effective one year following promulgation of the final rule in the Federal Register. However, three new work practice provisions for startup and shutdown have been added to Table 3 of the NESHAP to address situations where facilities cannot meet the current rule’s compliance obligations at all times (effective on and after one year after promulgation of the final rule in the Federal Register). The first work practice covers safety-related shutdowns of equipment that is required to be routed to a control device. During a safety-related shutdown, operators will need to follow documented procedures to protect workers and equipment, remove materials and heat from the equipment, and minimize air emissions. A safety-related shutdown could involve an indication that there might be a fire in or around a controlled source, insufficient air flow in process or pollution control equipment, plugging of pneumatic systems, or detection of high temperature in a control device.

The second work practice covers startup and shutdown of pressurized refiners. The work practice limits the amount of time when wood is being processed through the refiner and emissions are not being routed through the dryer to the emissions control system to less than 15 minutes. The third work practice covers veneer dryer gas burner lighting and re-lighting, which the current rule characterizes as a startup activity and not a malfunction. Facilities must cease feeding green veneer and minimize the amount of uncontrolled emissions during a burner re-light.

In response to comments received on the 2019 proposed rule, U.S. EPA adjusted the wording of the work practice requirements and added recordkeeping and reporting requirements. Facilities must maintain a record of their work practice procedures and record when the work practices are utilized. If the work practices are utilized for more than 100 hours during a semi-annual reporting period, a more detailed report is required. Electronic compliance reporting via the Compliance and Emissions Data Reporting Interface (CEDRI) is required for the first full reporting period after the CEDRI reporting form has been available for one year (which could be the January 2022-June 2022 reporting period).

Additional Testing Requirements

U.S. EPA finalized a requirement to perform repeat emissions testing within three years of promulgation of the final rule or within 60 months of the previous test, whichever is later. The test report must be entered into the online Electronic Reporting Tool (ERT). The final rule clarifies that repeat testing is not required for press capture efficiency if the capture device is maintained and operated consistent with its design and operation during the previous capture efficiency demonstration (see new footnote to Table 7). U.S. EPA also revised Tables 2 and 7 to indicate an annual regenerative catalytic oxidizer (RCO) catalyst check is not required during a calendar year when a performance test is conducted. The final rule also allows for an additional variability margin to be added to the biofilter temperature operating range developed during testing. A notification of compliance status (NOCS) is required following the repeat testing.

Sources Without Emission Limits or Work Practices

There are several emissions units that are part of the affected source under the PCWP NESHAP but have no requirements that limit their HAP emissions, such as lumber kilns and certain types of presses. A 2007 court decision remanded the rule (without vacatur) to U.S. EPA for further rulemaking to address HAP emissions from these units. The revised rule does not include any new requirements for the remanded units, but U.S. EPA has indicated that another rule revision will be proposed that addresses that equipment. ALL4 will be tracking the development of those requirements.

Summary

If your facility is subject to the PCWP NESHAP, review the final rule to determine how the revisions affect your plant or contact us for compliance assistance. Potential tasks could include the following, among others:

- When the final rule is published in the Federal Register, reviewing the new CEDRI reporting template and a redline/strikeout copy of the regulatory text that will become available at that time. These items will help you to determine what adjustments to your facility’s systems, procedures, and plans are needed over the next year.

- Determining if new programming is required to address the new startup and shutdown work practices and new recordkeeping requirements.

- Developing algorithms to estimate excess emissions due to deviations from compliance requirements.

- Creating the required documentation of the new work practice procedures, which could take the form of revising your existing SSM Plan and recategorizing it as an emissions minimization plan that documents the steps you will take that are aligned with the new work practice standard requirements.

- Updating your biofilter temperature operating range, if applicable.

- Reviewing updated temperature sensor validation options.

- Establishing an updated compliance calendar that includes the date of the next performance test and/or catalyst check that will be required.

Stay tuned for additional RTR updates, and contact Amy Marshall with questions or for assistance with PCWP NESHAP compliance planning.

What O&G Facility Owners and Operators Need to Know about the Proposed PA CTG RACT Rule

On Saturday, May 23, 2020, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP) posted a proposed Reasonably Available Control Technology (RACT) rule in the Pennsylvania Bulletin for the control of volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions from “existing” oil and natural gas sources, commonly referred to as the control techniques guidelines (CTG) RACT Rule. Comments on the proposed CTG RACT Rule are due to PADEP by July 27, 2020. The proposed CTG RACT Rule establishes the VOC emissions limitations and other requirements of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) recommendations in the Control Techniques Guidelines for the Oil and Natural Gas Industry (2016 O&G CTG). The level of VOC control expressed in the CTG RACT Rule is comparable to the requirements of 40 CFR Part 60 Subpart OOOOa. U.S. EPA has proposed to withdraw the 2016 O&G CTG. If the 2016 O&G CTG is not withdrawn, states with ozone nonattainment areas (and subject to RACT requirements) must revise their State Implementation Plans (SIPs) for the 2008 and later ozone standards to include RACT standards for existing oil and natural gas sources covered by the 2016 O&G CTG no later than January 21, 2021. It is important to note that PADEP does not plan to abandon the CTG RACT Rule even if the 2016 O&G CTG is withdrawn by U.S. EPA. We expect that PADEP will still work to establish the emissions standards by the January 21, 2021 deadline regardless.

The CTG RACT rule is proposed as 25 Pa Code §§129.121 – 129.130 and will regulate VOC emissions that are associated with existing oil and gas operations in Pennsylvania. The rule defines existing as oil and natural gas sources that are in existence on or before the effective date of the proposed rulemaking when published as a final-form rulemaking. PADEP estimates that the rule will apply to over 89,000 unconventional and conventional oil and natural gas wells (of which over 8,400 unconventional and over 71,000 conventional wells are currently in production), approximately 435 midstream compressor stations, 120 transmission compressor stations, and 10 natural gas processing facilities. The sources affected by the proposed CTG RACT Rule are:

- Storage vessels

- Natural gas-driven pneumatic controllers

- Natural gas-driven diaphragm pumps

- Reciprocating and centrifugal compressors

- Fugitive emissions components

In two cases, PADEP determined that more stringent RACT requirements than the 2016 O&G CTG are necessary:

- PADEP proposes a lower VOC applicability threshold is for storage vessels at unconventional well sites installed on or after August 10, 2013 to prevent backsliding, which will also represent RACT for storage vessels at gathering and boosting stations, processing plants, and transmission stations.

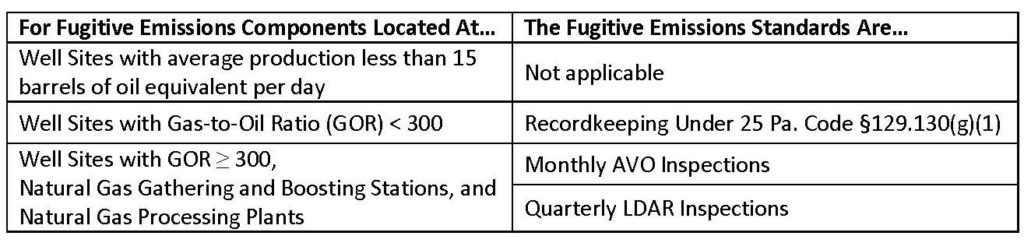

- PADEP proposes that owners and operators conduct monthly audio, visual, and olfactory (AVO) inspections and quarterly leak detection and repair (LDAR) inspections of fugitive emissions components at their facilities vs. semiannually for fugitive emissions components at well sites and quarterly for fugitive emissions components at gathering and boosting stations as recommended in the 2016 O&G CTG.

PADEP states that only a limited number of conventional well sites will be subject to LDAR monitoring based on the proposed 15 barrels of oil equivalent per day production threshold, but that other requirements will require conventional operators to assess applicability and take action to comply, as applicable (e.g., storage vessel provisions).

A summary of the proposed CTG RACT Rule as it applies to the affected sources is provided below.

Storage Vessels:

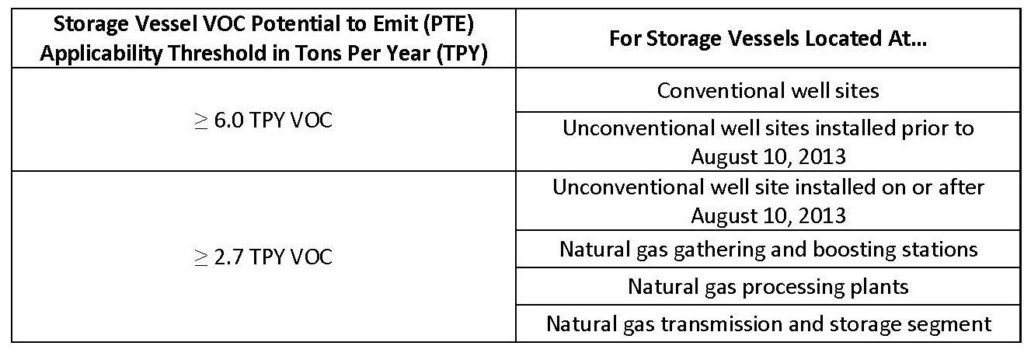

The proposed CTG RACT Rule requirements will apply to storage vessels that meet the following applicability thresholds:

The PTE is to be determined using a generally accepted model or calculation methodology, based on maximum average daily throughput. Owners or operators of storage vessels exceeding the PTE thresholds described above must reduce VOC emissions by 95.0% by weight or greater by either (1) routing the VOC emissions to a control device or process through a closed vent system, or (2) equipping the storage vessel with a floating roof that meets the requirements of 40 CFR Part 60, Subpart Kb. There are certain exceptions and categorical exemptions to the storage vessel requirements proposed at 25 Pa. Code §§129.123(c) and (d).

Natural Gas-Driven Pneumatic Controllers:

The CTG RACT Rule requirements will apply to natural gas-driven pneumatic controllers located prior to the point of custody transfer of oil to an oil pipeline or of natural gas to the natural gas transmission and storage segment. Owners or operators must tag all affected natural gas-driven pneumatic controllers with the compliance date and an identification number and also must ensure that the natural gas bleed rate of the controller meets the following standards:

- ≤0 standard cubic feet per hour (SCFH) if located either (1) between a well head and a natural gas processing plant or (2) between a well head and a point of custody transfer to an oil pipeline.

- Zero SCFH if located at a natural gas processing plant.

Natural Gas-Driven Diaphragm Pumps:

The CTG RACT Rule requirements will apply to natural gas-driven diaphragm pumps located at a well site or natural gas processing plant. The standard for affected natural gas-driven diaphragm pumps is to reduce VOC emissions by 95.0% by weight or greater by complying with the following:

- At well sites: route the VOC emissions to a control device or process through a closed vent system.

- At natural gas processing plants: maintain a VOC emissions rate of zero SCFH.

There are certain exceptions and exemptions to the pump requirements proposed at 25 Pa. Code §§129.125(c) and (d).

Compressors:

The CTG RACT Rule requirements will apply to reciprocating compressors and to centrifugal compressors using wet seals located between the wellhead and point of custody transfer to the natural gas transmission and storage segment. Compressors at transmission compression stations are not subject to the rule. The proposed standards for affected compressors are as follows:

- Reciprocating compressors: replace the rod packing on or before the reciprocating compressor has operated for 26,000 hours or 36 months. Alternately, the owner/operator may route the VOC emissions to a process by using a reciprocating compressor rod packing emissions collection system that operates under negative pressure and meets the requirements of 25 Pa. Code §129.128(a).

- Centrifugal compressors using wet seals: reduce VOC emissions from each centrifugal compressor wet seal fluid degassing system by 95.0% by weight or greater by equipping the wet seal fluid degassing system with a cover that meets the requirements of 25 Pa. Code §129.128(a) and routing emissions through a closed vent system to a control device or a process.

There are certain exemptions to the compressor requirements proposed at §129.126(d).

Fugitive Emissions Components:

The CTG RACT rule requirements for fugitive emissions components are proposed as follows:

Other requirements related to fugitive emissions components under the CTG RACT Rule include development of a fugitive emissions monitoring plan, procedures for verification and operation of optical gas imaging (OGI) equipment and for U.S. EPA Method 21 gas leak detection equipment, leak repair requirements, and options for decreased or extended LDAR inspection intervals. The frequency of required LDAR inspections may be decreased to semi-annually if less than 2% of fugitive emissions components are found to be leaking for two consecutive quarterly surveys.

Additionally, the CTG RACT Rule includes significant requirements associated with covers, closed vent systems, and air pollution control devices. Administrative requirements include monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting which includes the preparation, certification, and submittal of an initial compliance report one year after the effective date of the published final rule, and annually thereafter, to PADEP. The preamble to the proposed rule mentions the availability of “case-by-case” RACT analyses if the owner or operator cannot meet the provisions of the proposed rulemaking, but such provisions are not explicit in the rule proposal.

If you have questions about how the Pennsylvania CTG RACT Rule or other air quality regulations may apply to your facility, please reach out to me at kfritz@all4inc.com or 610-933-5246 x116.

What to Expect When You’re Expecting a CFATS Compliance Inspection

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) administers the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS) program, intended to set standards and monitor the security of listed hazardous chemicals stored at certain locations. Each “high risk” facility covered by the CFATS program is required to submit and maintain an Alternative Security Program (ASP) or Site Security Program (SSP), which contains security measures that sufficiently meet all Risk-Based Performance Standards (RBPS). Once your ASP or SSP has been approved and timelines for implementing planned measures have expired, DHS will reach out to schedule your first compliance inspection. What do you need to know before your inspector shows up?

Logistics

While DHS can show up at your facility unannounced, typically DHS will reach out to schedule your compliance inspection. Depending on the size of your facility and the number of chemicals of interest (COIs), the inspector will may plan to be onsite for 1-2 days. However, with sufficient prep work on your part, the inspector may get everything he or she needs within 2-4 hours onsite. Let the inspector know what personal protective equipment (PPE) they will need to have to come onsite, and coordinate providing any PPE they may not have.

Ensure that all necessary individuals are available to participate in the inspection as needed, including your Facility Security Officer (FSO), Plant Manager, Human Resources, Chemical of Interest (COI) area “owners,” security personnel, training managers, Project Managers/Engineers for any physical security upgrades required by the SSP or ASP, and Information Technology (IT) personnel. Ensure that all individuals are Chemical-Terrorism Vulnerability Information (CVI) Authorized Users and obtain copies of all of their CVI certificates – your inspector will ask to see these before beginning the inspection. Plan to have all individuals attend a kick-off meeting once the inspector arrives. The kickoff meeting should be used to clearly define the purpose of the inspection, the plans for the day, the expectations of the inspector, and safety and emergency procedures for the site. The inspector may ask for some individuals to stay and for others to remain available in the event of questions. Upon completion of the inspection, conduct a close-out meeting with the group. The inspector will review findings and there will an opportunity for all parties to ask questions.

Documentation Review

The better prepared you are for your compliance inspection, the more efficient the inspector can be with the on-site portion of the inspection. It is best to pull together all records and documentation ahead of the inspection and store these documents in a binder. For each type of record required, pull a few sample records to show the inspector. If you do not have any completed records, for example if you have not had any security breaches, provide your recordkeeping template that would be used when needed. Be sure to have the following information handy:

- A diagram or map of your facility for reference if needed

- SSP or ASP

- Date of implementation for all planned security measures

- Training records

- Key access logs, as applicable

- Records of security breaches

- Records of drills and exercises

- Emergency Response Plan

- Policies or procedures pertaining to existing or planned security measures

- Annual self-audit

- Security post-orders

- Security logs (e.g. round sheets, visitor sign-in logs)

- Communication with law enforcement, including invitation to come onsite

- Maintenance records for security equipment

- COI inventory on the day of inspection in pounds (the inspector will compare against the maximum inventory in the most recent Top-Screen)

- List of individuals who were background checked as required by RBPS 12, with the date that background checks were completed

- IT network map, name of firewall and operating system

Physical Inspection

The inspector will likely want to lay eyes on your COI(s), their respective control rooms, and any physical security upgrades required by your SSP or ASP. The inspector may also ask questions regarding the facility perimeter and facility entrance points. If you have security cameras installed, the inspector may ask for operators or security guards to roll back the footage to a night-time view. The inspector may ask questions of the security personnel and/or operators.

After the Inspection

If this was your initial compliance inspection and your SSP or ASP included planned security measures, the inspector will likely recommend submitting an updated SSP or ASP to reflect that your planned security measures are now existing security measures. This update will make future compliance inspections even simpler. If you are a Tier 3 or 4 facility and have not yet been notified by DHS of the requirement to screen employees with access to the COI for terrorist ties, you can wait until you have received that notification to submit your updated SSP or ASP – see our previous article on personnel surety for more information.

COVID Impacts

DHS is currently restricting travel and is not conducting in-person inspections. We have heard of some inspectors planning to conduct inspections virtually, with a follow-up site visit for the physical inspection in the coming months. Virtual inspections may include sending copies of your records and documentation physically or electronically to your inspector and setting up a conference call to review. When sending CVI material physically or electronically, be sure to follow the instructions on the CVI cover sheet.

If it has been a year since your SSP or ASP approval and you have not been contacted by DHS for an inspection, or if it has been more than 12-18 months since your previous compliance inspection, reach out to your DHS contact to ask how they are planning to handle inspections in the near-term.

ALL4 provides CFATS compliance inspection support and can help you prepare for and succeed in your compliance inspections. For all of your CFATS-related questions, please contact me at lsmith@all4inc.com or at (770) 999-0269. Look for more CFATS content from ALL4!

Ready to Reopen? Don’t Forget to Check Your Water Systems!

There are many articles out there about preparing stagnant buildings for reopening, and they contain valuable information. One topic that’s commonly discussed is the hazard with uncirculated or untreated water, particularly the potential for legionella growth.

As you prepare to safely re-enter buildings, these reminders can help you get started:

- Coordinate plans with your Environmental, Health, and Safety personnel and your water treatment vendor/chemical supplier.

- Key considerations – safety of personnel sampling water, evaluating hazards of additional chemicals required to treat stagnant water, and maintaining documentation of steps taken to prepare for reopening.

- Identify equipment and water connections where legionella can grow.

- This can include water distribution systems, hot water systems, closed-loop systems such as cooling towers and boilers, and water collection points like HVAC drainage pans.

- To ready your municipal drinking water, flush the system until you are satisfied with the level of residual chlorine at the furthest tap in the system.

- For added comfort, collect water samples and send them to a lab to test for legionella.

- To ready your well-sourced water, flush the system, ensure an adequate chemical supply to disinfect/treat the water, and test water samples for residual chlorine, legionella, and other waterborne bacteria such as coli.

- To ready your closed-loop systems, coordinate with your water treatment vendor/chemical supplier to treat the water.

- This may require an increased dosage of chemical to mitigate the impacts of stagnation.

- Testing of water samples may be required.

- Inspect and drain water collection points of excess moisture prior to opening the building.

- If new chemicals are used for water treatment during the building re-start, evaluate those under your “Chemical Approval” policy/procedure.

- Recommendations for after reopening:

- Continue routine legionella testing.

- Compile a procedure for future events based upon steps taken to prepare for reopening, including information about vendors, chemicals/dosages, analyses performed/lab used, and recommendations for improvements based upon lessons learned.

If you’re looking to establish a water management program, the Virginia Department of Health provides a helpful summary (https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/drinking-water/legionella-information-for-consumers-and-building-owners/) and refers to additional resources from the Centers for Disease Control, including this toolkit: https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/downloads/toolkit.pdf

For support with programs and procedures for your building’s water systems, or other EHS consulting needs, please contact Sharon Sadler (ssadler@all4inc.com or 571.392.2595).

Georgia’s Air Permit Fees are Increasing

The Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GEPD) needs to increase permit fees to keep up with business growth in the state. A few things have happened to cause the need for this increase. In 2017, GEPD lost $2.2 million in fees when coal-fired power plants in Georgia closed. In 2019, two more coal-fired power plants closed and will cause a loss of $657,937 in the fiscal year 2021. While emissions have decreased and GEPD has cut their staff in half, workload has not decreased. GEPD did build reserves in 2015-2017 to delay these needed permit fee increases, but the time has come.

On March 1, 2019, permit application fees were updated to the following:

- Generic (Minor Synthetic Minor) Permit Fee: $0

- Title V Initial and Renewal Fee: $0

- Off-Permit Change Request Fee: $0

- No Permit Required Exemption Fee: $0

- Minor Source Permit of Amendment Fee: $250

- Name / Ownership Change Fee: $250

- Permit-by-rule Fee: $250

- Synthetic Minor Source Permit or Amendment Fee: $1,000

- Title V Modifications and 502(b)(10) Permit Amendment Fees: $2,000

- Major Source Permit not Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) or 112(g) Fee: $2,000

- PSD Permit Fee: $7,500

- 112(g) Permit Fee: $7,500

- Nonattainment New Source Review (NSR) Permit Fee: $7,500

In addition to those updates, GEPD wants to make the following changes to be implemented in July 2021:

- Raise the annual synthetic minor permit fee to $2,100/year (previously $1,700/year)

- Raise the annual New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) fee to $1,900/year (previously $1,500/year)

- Increase expedited permit fees by 25%

- Add an annual maintenance fee for all Title V sources of $650/year

The proposed changes move towards a more equitable distribution of fees between types of work. The goal of these changes is to increase future stability of funding for delegated permitting programs. The second set of changes to be implemented in July 2021 are in the review process.

Here is GEPD’s timeline:

- February 2020: brief board on FY2021 fee revisions (Complete)

- March/April 2020: public comment period and public hearing (Complete)

- May 2020: request board adoption for FY2021 fee revisions (In progress, confirmation expected in June)

- July 1, 2020 (first day of FY 2021): new fees become effective

- September 1, 2020: annual fee payments due

- March 1, 2021: proposed changes in expedited fees and permit application fees become effective

GEPD has more information on their website below, including their presentation from their January Stakeholders Meeting.

If you’d like to learn more about air permitting and associated fees in Georgia, please reach out to me at mjones@all4inc.com or 678-460-0324 x215.

Update on Regional Haze Rule Activity

Background

The Regional Haze Rule (RHR) was promulgated in 1999 at 40 CFR Part 51, Subpart P. The U.S. EPA developed the RHR to meet the Clean Air Act (CAA) requirements for the protection of visibility in 156 scenic areas (Class I areas) across the United States. The goal of the RHR is to return visibility in these areas to natural conditions by 2064. The RHR established visibility milestones for each planning period called the uniform rate of progress (a.k.a. glide path) at each Class I area. States must make reasonable progress toward this goal during each planning period. The first stage of the RHR required that certain types of existing stationary sources of air pollutants evaluate Best Available Retrofit Technology (BART). The purpose of the BART evaluations was to identify older emissions units that contributed to haze at Class I areas that could be retrofitted with emissions control technology to reduce emissions and improve visibility in these areas by 2018. The initial round of RHR state implementation plan (SIP) revisions that addressed BART requirements were due in December 2007.

What’s Happening Right Now?

States are currently in the process of developing SIP revisions for the second RHR planning period, following the 2017 U.S. EPA RHR revisions and 2018-2019 final guidance documents. SIP revisions are required by July 31, 2021 and must address further controls that could be applied to stationary sources to reduce emissions of visibility impairing pollutants during the 2021-2028 period. Some states have made more progress than others in the evaluation of what further controls are feasible in order to make progress on visibility improvement goals during this planning period.

The approach to selecting sources to be evaluated has varied from state to state. Some states are selecting sources within certain industries that are large emitters of sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOX), and particulate matter less than 10 microns (PM10). For example, Washington focused primarily on combustion sources in industries such as power, pulp and paper, and refining. Some states developed a threshold based on the facility’s emissions of visibility impairing pollutants in tons per year (Q) divided by their distance in kilometers to the closest Class I area (d) and selected the facilities above the threshold for evaluation. For example, Oregon has selected all facilities with Q/d of at least 5 for evaluation and asked facilities to evaluate all emissions sources that are not classified as insignificant activities. Wyoming selected facilities with a Q/d of at least 10 and asked facilities to evaluate units with the largest emissions of SO2, NOx, and PM10. Some states performed a modeling analysis to determine the facilities with the largest impact on visibility impairment in Class I areas and selected sources above a certain threshold for analysis (e.g., the Southeastern States). Finally, some states asked for evaluations on individual emissions units at facilities (e.g., Minnesota).

The pollutants to be evaluated also can vary from state to state. For example, Washington requested an analysis of SO2, NOx, PM10, ammonia, and sulfuric acid mist. Oregon is focusing on SO2, NOx, and PM10. (Oregon is also focusing on allowable emissions, rather than actual emissions.) The southeastern states have determined that SO2 emissions have the greatest impact on visibility impairment and are focusing on that pollutant.

What’s Involved in the Evaluation of Controls?

If your facility or a group of sources at your facility is selected for evaluation, a Four Factor Analysis will be required. The four factors are:

- The cost of control,

- Time necessary to install controls,

- Energy and non-air quality impacts, and

- Remaining useful life of the source.

Note that unlike the BART analyses we conducted for the first planning period, the four factor analysis does not include air dispersion modeling.

Many of us are familiar with the first and third factors because we routinely evaluate technical and economic feasibility of controls and the associated energy and non-air quality impacts of potentially feasible controls as part of permitting exercises or state air quality improvement initiatives. The U.S. EPA’s Control Cost Manual contains recommended procedures for developing capital and operating cost estimates for controls that are determined to be technically feasible. Often the framework outlined in the manual is adjusted using a vendor’s equipment cost estimate or equipment cost data included in other similar facilities’ permit applications or in industry studies, rather than using the complex equations in the cost manual to size and cost control equipment. Cost factors that should not be overlooked include the cost of new ductwork or fans, cost to replace a stack to accommodate a wet plume, cost of an unplanned shutdown (if required to install controls), and any cost required to demolish or move existing equipment to make space for new control equipment. The annual cost of installing additional controls or improving existing controls is divided by the expected reduction in emissions to develop a cost per ton estimate.

The other two factors, time necessary to install controls and remaining useful life of the source, are important because the states are evaluating improvements that can be made in order to improve visibility in the 2021-2028 time period. If it will take 10 years to install a control or if the emissions unit will be shut down between 2021 and 2028, the outcome of the analysis will be different than if an emissions reduction can be accomplished quickly and the emissions unit has 20 more years of life. If a control technology is determined to be technically and economically feasible, a compliance deadline will be established based on the estimated time necessary to install controls.

Although states have not indicated they have a certain threshold in mind for determining whether additional control is cost effective, the fact that many Class I areas are well below the glidepath (visibility is better than many areas’ goal) for the second planning period is likely to mean that the cost per ton threshold is lower than it would be in a traditional permitting analysis. When the U.S. EPA was evaluating whether NOx controls would be cost effective for non-electric generating unit sources for the 2017 Cross State Air Pollution Rule update, it used a threshold of $3,400/ton. There have been several non-RHR related air regulatory programs in the past 10 years that have resulted in reductions in emissions of SO2, NOx, and PM10 and improved visibility in Class I areas, so the number of sources required to make emissions reductions during the second planning period may not be significant. However, the fact that visibility is better than expected does not relieve the states from requiring a four factor analysis from selected facilities (it may allow for more flexibility in which sources are selected, though).

The four factor analysis approximates an evaluation of reasonably available control measures and does not have to be as stringent as a best available control technology (BACT) analysis. U.S. EPA guidance also indicates that it is reasonable for states to determine that sources complying with various federal air quality regulations, those with recent BACT limits, those firing clean fuels, and combustion sources with SO2 and NOx controls that are at least 90 percent effective are not candidates for additional controls.

What’s Next?

States will utilize the results of the four factor analyses and projected 2028 emissions to conduct modeling against baseline emissions and determine the progress they expect to make improving visibility during the second planning period. The control measures that will be implemented during the second planning period will be included in the RHR SIP revisions that are due next July. Measures could include work practices, addition of controls on uncontrolled sources, improvements of less effective controls, year-round operation of existing controls, fuel changes, and operating restrictions. Prior to incorporating control measures into the RHR SIP there will be dialogue between the states and the regulated community and an opportunity to provide comments on the draft SIP.

The U.S. EPA announced in January 2018 that it would revisit certain aspects of the 2017 RHR revisions in a notice and comment rulemaking. However, no action has been taken to date and the current rule and guidance documents are driving state actions for the 2021-2028 planning period. Any future U.S. EPA rulemaking action will impact the next planning period, and ALL4 will be on the lookout for any regulatory changes. If you haven’t heard how your state is handling regional haze evaluations, it is a good idea to check in with them and determine if your facility will need to take any action or provide any information as the state is working on their SIP. If you need assistance completing a four factor analysis, please contact Amy Marshall or your ALL4 project manager. We have completed analyses for various types of facilities in several states.